Fifty years ago this week, as military troops descended on the burning streets of Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University's Homewood campus was tense and still.

"The mood was apprehensive," says John Guess, who was an undergraduate at Hopkins in the spring of 1968.

He recalls the atmosphere on campus following the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4 that year, calling it a time of remorse, fear, and contemplation. The message from university administration, he recalls, was "stay in place, do not leave the campus." And for the most part, students complied.

Guess did not. "I went straight to downtown," he says.

He remembers a police dog rearing up on him as he made his way past the Homewood campus. Once in central Baltimore, he witnessed "tanks rolling down city streets," he says. "I'll never forget that image."

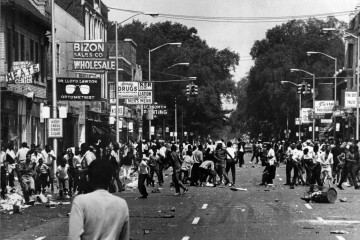

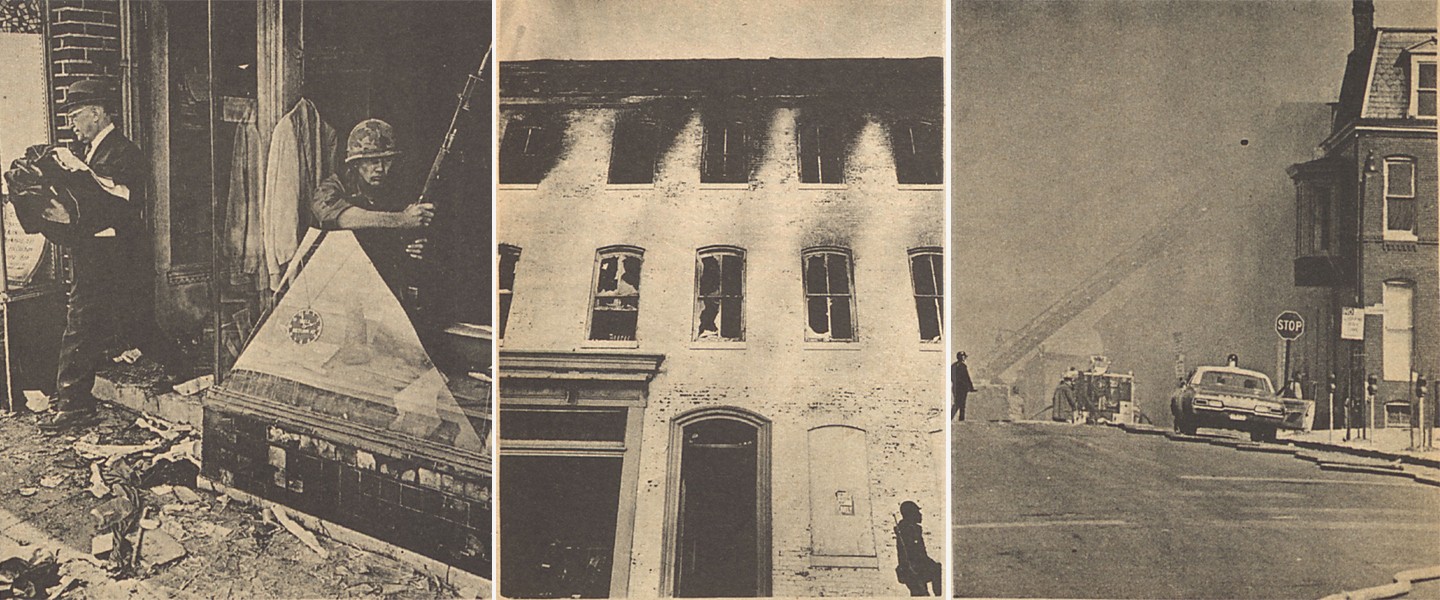

Image caption: For more than a week, the unrest raged, causing an estimated $12 million in property damage

Image credit: The Johns Hopkins News-Letter

The assassination of the civil rights leader unleashed protest and civil unrest across more than 130 U.S. cities, centered mainly in black communities. In Baltimore, the first glass window was smashed on the evening of Saturday, April 6, on the 400 block of N. Gay St. The rioting spread across the city, continuing through April 14. All told, the city saw six deaths, 700 injuries, 5,900 arrests, and an estimated $12 million in property damage, according to The Baltimore Sun. More than 1,000 businesses were damaged or robbed, and many of them would never reopen.

During the crisis, Maryland Gov. Spiro Agnew—a one-time Hopkins undergraduate—called upon the National Guard, the state police force, and federal riot-control troops to quell the violence.

Douglas Miles, now a civic leader in Baltimore and pastor at the Koinonia Baptist Church, was a commuter student at Hopkins in 1968. He witnessed the unrest firsthand in his home neighborhood of Reservoir Hill, seeing buildings on fire, bricks shattering store windows, and a preacher spouting words from a street corner.

When Miles returned to the Johns Hopkins campus later, he found "an atmosphere of terror and chaos." Students were locked down on campus, glued to the news. "I'm sure they smelled the smoke," he says.

But the campus on North Charles Street was, by and large, insulated from the mayhem that April.

"One, the area surrounding the school was predominantly white, and two, the National Guard protected it," Miles recalls. "The destruction was basically limited to African-American communities."

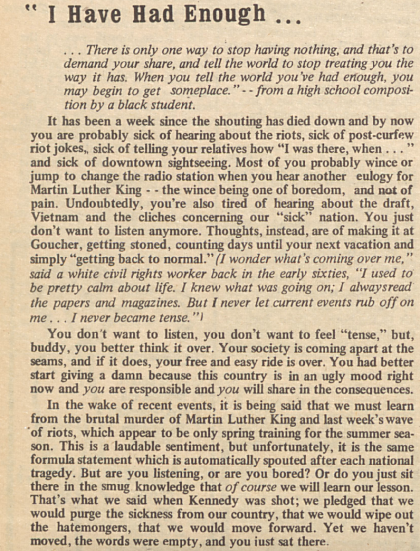

On April 5, the student newspaper, the Johns Hopkins News-Letter, published a brief statement about King's murder. But by the next edition, on April 19, the student newspaper conveyed a full sense of the tension and unease on campus. Though writers covered efforts at Hopkins to organize funds and aid for riot-torn parts of the city, they attacked what they viewed as apathy from both administration and students.

A sharply worded editorial warned students against slipping into complacency: "You had better start giving a damn because this country is in an ugly mood right now and you are responsible and you will share in the consequences."

Another writer, depicting the campus as a "green daydream in a night of burning," accused Hopkins higher-ups of being "out of place, out of reach" during the riots. He detailed controversy over an idea to hang the American flag upside down—instead of half-mast, as it was ultimately positioned.

Image caption: An editorial authored by staff writers at the JHU News-Letter called for greater compassion about the riots

Image credit: The Johns Hopkins News-Letter

At the center of the university's response to the riots was its chaplain, Chester Wickwire, who had already carved out a respected place for himself among Baltimore's civil rights community. Wickwire helped organize an April 22 memorial service for Dr. King in Shriver Hall, and, on the city level, he led a white protest group criticizing Gov. Agnew.

At an infamous meeting on April 11, Agnew had delivered controversial words to a large group of black leaders in Baltimore—who, in turn, walked out on him. The speech criticized the riots leaders as a "caterwauling, riot-inciting, burn-America-down type of leaders" and called upon those present to "publicly repudiate, condemn, and reject all black racists … [which] so far, you have not been willing to do."

Miles, who was beginning his clergy career at this time, heard the start of that speech in person.

"I was allowed at the table with pastors and politicians, who thought they were going to a meeting about moving forward after the riot … but were then dressed down by the governor," he recalls.

"I was angry," Miles adds. "I was as angry as any senior member of the community."

The News-Letter also condemned Agnew's speech, deeming it "condescending verbal abuse." The student paper also ran an ad from Wickwire—which The Baltimore Sun had rejected—calling on Agnew to "apologize for his ill-timed remarks" and for white citizens to "work for a rebirth of justice and opportunity in Maryland."

Guess—who came to Hopkins from Houston and today heads that city's Museum of African American Culture—had also become involved with Baltimore's black community in 1968, working with the local Congress of Racial Equality group. When he went downtown during the rebellion, he saw the familiar faces of local activists.

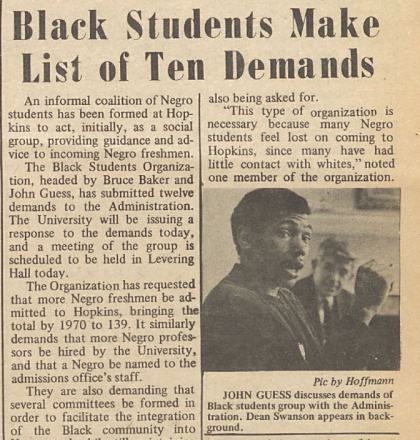

Image caption: By the fall of 1968, Johns Hopkins students would form the Black Student Union, demanding more courses on black history, more community action in Baltimore, and the enrollment of more black students.

Image credit: The Johns Hopkins News-Letter

"It ended up that the black community in Baltimore decided it was going to rebel against existing conditions … and reject policies of the city and state government that impacted their lives," he says.

Of the corresponding violence, Guess says: "You can agree or disagree whether that was a solution … but it certainly put a light on the problem." For some Baltimore citizens, he says, "the only power they had … was to throw a Molotov cocktail and a brick."

Guess left Homewood several times during the unrest, and he recalls that he would hustle by foot to return before the city-enforced curfew took effect at night.

On campus, it was a particularly tense few weeks for black students, who numbered only about 30 then, Guess and Miles among them.

Miles remembers chafing against pressure to act as a "spokesperson for African-Americans" with students and faculty pressing for explanations of the riots. "It was a time of great pain for African-Americans on campus," he says.

In the months immediately following the unrest, two notable developments emerged at Johns Hopkins.

First, the university formally established its Center for Urban Affairs, the predecessor to today's 21st Century Cities initiative, with the goal of making "significant contributions to the improvement of life in urban America."

Around the same time, Guess and his friend Bruce Baker activated to create the Black Student Union at Hopkins, pressing for a larger number of black students, more courses on black history, and community action in Baltimore, among other goals. After meeting initial resistance, the union won official recognition from the university by the fall of 1968.

To Guess, the birth of that group was related less specifically to Baltimore's riots and more to the national civil rights awakening of the era.

"Black people decided we needed to make some changes," he says.

Posted in University News, Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged civil rights, johns hopkins history