Fifty years ago this week, a Washington Post headline put it plainly: "Chief Blame for Riots Placed on White Racism."

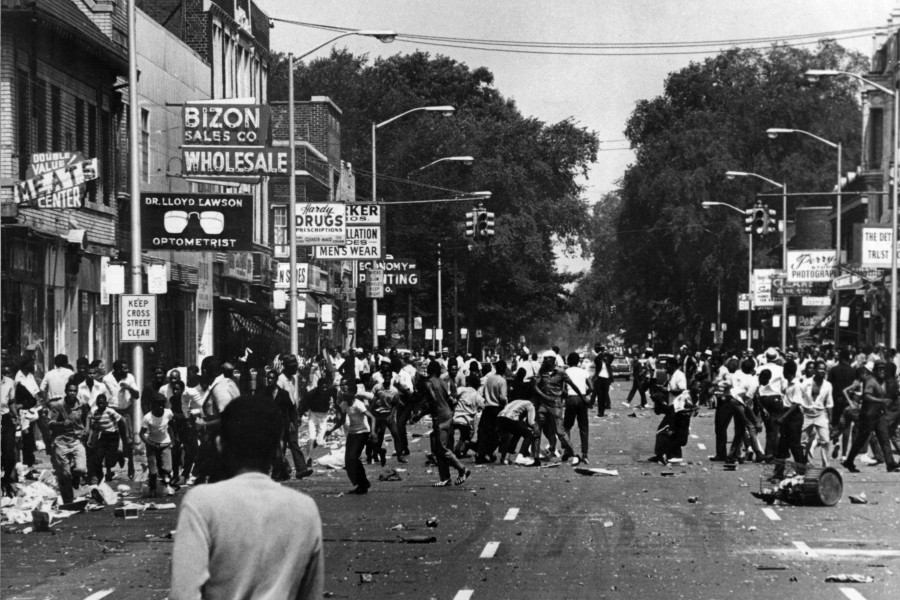

The newspaper had its hands on a fresh copy of the Kerner Report, the federal government's analysis of riots in black neighborhoods in dozens of U.S. cities in 1967, including violent protests in Detroit and Newark, New Jersey, that left 70 people dead.

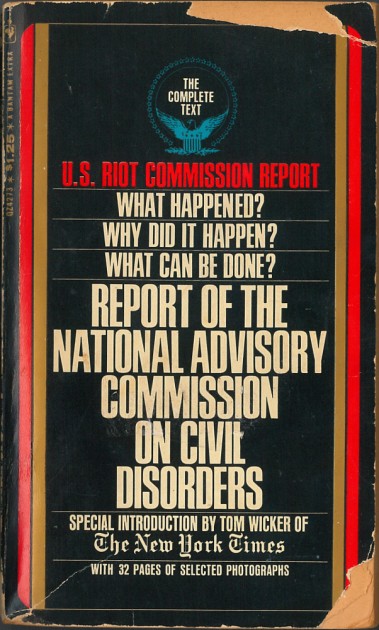

The report, which explored the causes of black unrest through interviews, data, and testimony, offered an unprecedented mainstream acknowledgement—and indictment—of the racism woven into the fabric of American society. The media was quick to devour the provocative findings, and the report itself, published in paperback, became a bestseller and national talking point.

Video credit: Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society

"Certainly then people weren't comfortable or familiar with a report, coming from the government, that was so hard-hitting," says Princeton professor Julian Zelizer, who wrote an introduction to a 2016 reissue of the text. "It's incredible to look back at, but even today it's hard to imagine the government producing any report that is this blunt."

Though the Kerner Report never brought about the massive policy shifts its authors recommended, its findings have remained relevant through the decades as the tensions of 1967 continued to reappear in new forms—most recently, in unrest over police brutality in cities such as Baltimore; Charlotte; and Ferguson, Missouri.

"Many are surprised at just how much the report revolves around the issue of policing," says Zelizer, a professor of history and public affairs and the author or editor of 18 books on American political history. "That's really the center of it, in addition to how the media portrays urban violence."

This week, to mark the 50th anniversary of the report, Johns Hopkins will co-host a three-day conference, along with the University of California, Berkeley and the Economic Policy Institute, examining the current state of race and inequality in America. The Kerner Commission at 50 will feature eight panel discussions, with speakers both at Baltimore's Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture and at Berkeley, with a live broadcast available at the Lewis Museum.

Zelizer is among the academics and policy experts who will contribute from Baltimore, along with a number of scholars from Johns Hopkins and Fred Harris, a former U.S. senator from Oklahoma and the only surviving member of the Kerner Commission.

The bipartisan, 11-member group—known officially the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, but commonly referred to as the Kerner Commission after its chair, Gov. Otto Kerner of Illinois—was appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson in July 1967. In the wake of riots in cities across the country, many of which saw black citizens clash violently with police, Johnson wanted to know what had happened, why it happened, and what could be done to prevent it from happening again. He challenged the group to "let your search be free, untrammeled by what has been called the 'conventional wisdom.'"

A first draft of the report, however, proved so inflammatory that the attorney in charge "cursed and screamed" while his colleague threw the pages against a wall, Zelizer wrote in his 2016 essay.

The final 426-page report, released in February 1968, maintained its provocativeness. An opening passage, which became the document's most memorable line, reads: "Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal."

The commission found that the riots were the result of black frustration at the lack of economic opportunity. It took aim at federal and state governments for their failed education, housing, and social service policies. As Zelizer writes, the report "blamed 'white racism' for producing the conditions that were at the heart of the riots," tracing the history of racial unease all the way back to slavery. Commissioners focused attention on institutional forces such as unemployment, housing discrimination, and particularly the police.

Image caption: President Lyndon B. Johnson addresses the nation from the Oval Office about urban riots and civil disorder on July 27, 1967. The next day, he signed an executive order establishing the Kerner Commission to study what had caused the riots and what could be done to prevent them from happening again.

Image credit: LBJ Library

In a marked contrast from past government reports on racial unrest, the Kerner Commission portrayed the rioters not as "riff-raff" but as mostly educated, middle-class Americans "who could no longer withstand the deplorable conditions under which they and their families lived," Zelizer writes.

Unhappy with the findings and the flaws they revealed in his "Great Society" agenda, Johnson ultimately distanced himself from the Kerner Report, even refusing to sign thank you cards to the commissioners.

Though the commissioners endorsed a set of policies to promote racial integration, the report "never became much of a guide toward public policy," Zelizer writes, though he notes its influence on the fair housing act of 1968 and social programs of the era, such as Medicaid and food stamps, that aimed to alleviate poverty.

The 708-page paperback version of the Kerner Report sold more than 740,000 copies, with public interest surging after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968—an event that sparked a new round of urban riots.

Ben Seigel—director of Johns Hopkins' 21st Century Cities initiative, which is co-sponsoring this week's conference—says the Kerner Report's call for advancing economic opportunity and racial integration resonates strongly today.

"The Kerner Report outlined bold policy proposals for addressing racial disparities in American cities across a range of indicators, including housing, jobs, and education," Seigel says. "The 50th anniversary is an important time to reflect on what might have been if more of these recommendations were fulfilled—and on the continued need for research-based policies that narrow inequality in urban neighborhoods."

Race and Inequality in America: The Kerner Commission at 50 will take place Feb. 28—March 1 at the Reginald Lewis Museum at 830 E Pratt St., with speakers simulcast live from both Baltimore and Berkeley. Headliners include Shaun Donovan, former U.S. secretary of Housing and Urban Development; and Sherrilyn Ifill, president of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund; and Harris.

From Johns Hopkins, speakers include:

- Ronald J. Daniels, Johns Hopkins University president

- Lisa Cooper, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor, social epidemiologist, and health disparities researcher

- Stefanie DeLuca, professor of sociology and social policy

- Robert Lieberman, professor of political science

- Lester Spence, associate professor of political science and Africana Studies

- David Steiner, professor of education and director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy

More details, including registration information and a complete schedule, are available at 21cc.jhu.edu/kerner50.

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged race relations, 21st century cities, public policy, urban policy