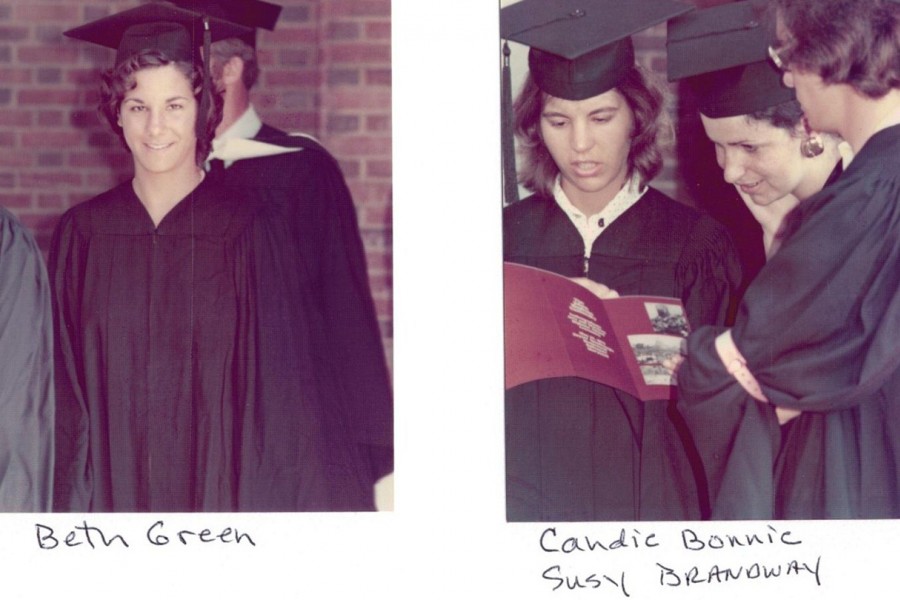

Before the first female undergraduates at Johns Hopkins collected their diplomas, one young woman delivered a speech on their behalf. It was commencement, May 1974.

"When we first came here, many of us found that we were not entirely welcome," Cynthia Young told the crowd. There were times, she said, when "we felt compelled to prove ourselves superior, in order to be considered equal."

The senior had crafted the lines with a few other female students at Hopkins, who elected her as speaker. They hoped to share some sense of their distinct and challenging experience at Hopkins, as the women to who put an end to 94 years of male-only enrollment.

Image credit: Courtesy of Mindy Farber

While Hopkins had hosted a few high-profile female grad students and professors throughout the 1900s, it wasn't until 1970 that the university began admitting women as undergrads.

Young's speech recounted some surprises that greeted these young women: infirmaries sequestered in broom closets, male supervision required for ping-pong, professors referring to their assembled students as "gentlemen."

Today, Young, who works as a lawyer, remembers another symbol: fake flowers placed in urinals, to mark a ladies room.

"I don't think Hopkins was ready in all aspects for women," she says.

Before Hopkins broke its all-male tradition, the community had debated the issue thoroughly. The move followed a wave of other major universities embracing co-education, and many at Hopkins welcomed the chance for a larger, more diverse pool of applicants.

The transition was abrupt but modest, with 90 women starting classes in the fall of 1970, both as freshmen and as upper-level transfer students.

Many women were locals from in and around Baltimore. Some were married; a few were mothers already.

Linda Pickle, who got married and had her daughter right after high school, was taking classes at a community college before her adviser encouraged her to transfer to Hopkins.

"My reaction was, 'Who, me?'" says Pickle, who ultimately went on to earn her PhD in biostatistics from Hopkins.

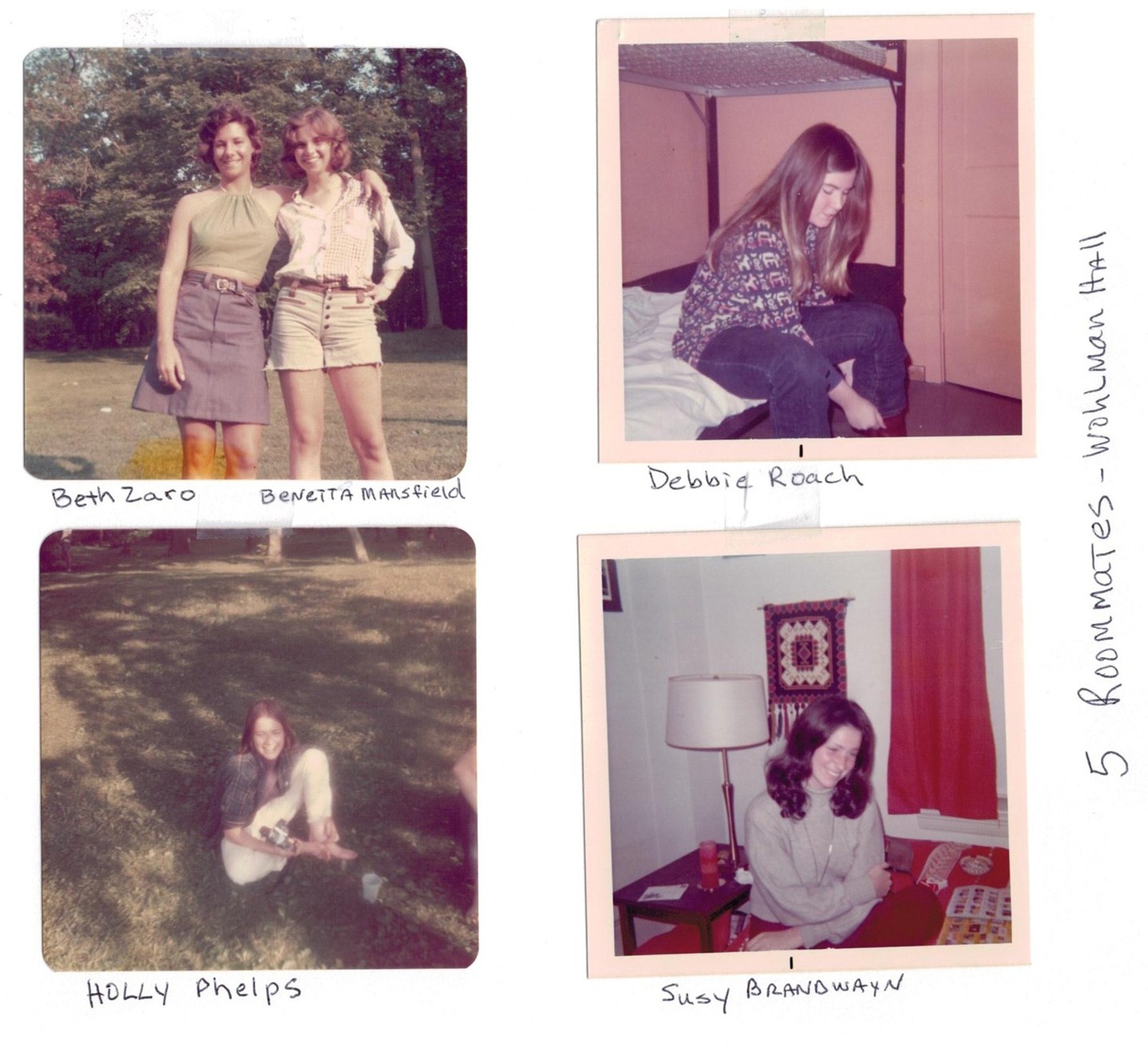

But the university also drew many out-of-towners, who lived on campus in a few dorms reserved for women.

Mindy Farber, who came from Long Island, recalls getting a sweet deal from housing mixups: A spacious one-bedroom to herself, in coveted Wolman Hall.

Image caption: Johns Hopkins University admitted female undergraduate students for the first time in the fall of 1970, a change that abruptly altered both the academic and social dynamics on campus.

Image credit: Courtesy of Mindy Farber

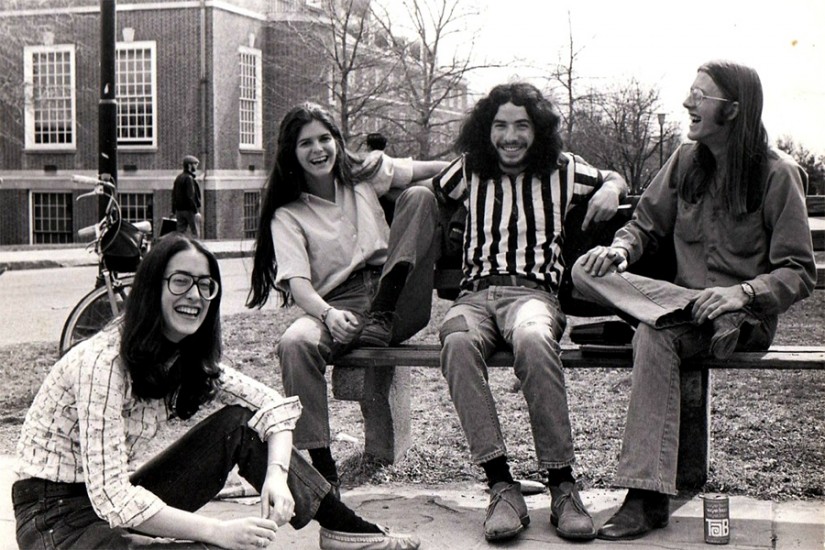

The uneven ratio of males to females made for complex dynamics, both academically and socially.

Pickle recalls: "Several professors never called on me. I felt invisible." That was fine during her first days, when she was "still nervous about being there at all." But she found a refreshing change in public health school courses during her senior year, "when the professors were used to having women in class and seemed to treat us equally."

Farber, who is also now a lawyer, remembers "lopsided" classes where men would choose seats far from the women. But socially, she says, the two genders mixed easily as friends and couples.

For Young, the demographics resulted in her finding "15 or 18 brothers," she says.

Though some female students simply went about their studies, the activists among them saw opportunities for reform at Hopkins.

"We did a lot to get things changed," says Farber, recounting successes in creating a dedicated health clinic for women, a women's history class, and a women's sports team (soccer).

Farber herself helped found a Women's Center, which organized "Next Step: A Festival for Women" in 1974. They scored university funding to draw big-name speakers, including Jane Fonda and Shirley Chisholm, the first black woman elected to Congress.

Image caption: Among the notable speakers the university's first female undergraduates brought to campus were Shirley Chisholm, the first African-American woman elected to Congress, and Jane Fonda, pictured here.

Image credit: Courtesy of Mindy Farber

United by their singular experience of Hopkins, many women of the Class of 1974 have stayed connected with one another through reunions. Their ranks today include doctors, lawyers, business owners, and two Gails of note: Gail McGovern, president and CEO of the American Red Cross; and HIV/AIDS policy advocate Gail Kelly, one of the first three black women undergraduates at Hopkins.

At their commencement, back on May 24, 1974, the women numbered about 68, within a class of about 485 total. This was the first graduating class including females that made the full four-year run at Hopkins.

In her speech that day on Keyser Quad, Young spoke for the women who continued to push for more progress.

"In the future, Hopkins women should not have to experience any more dramatic transitions," the speech read. "We hope they will be part of the process of change. In contrast, we in this graduating class were the instruments of change."

Posted in University News, Student Life, Alumni

Tagged alumni, commencement, university history, women, women's history month