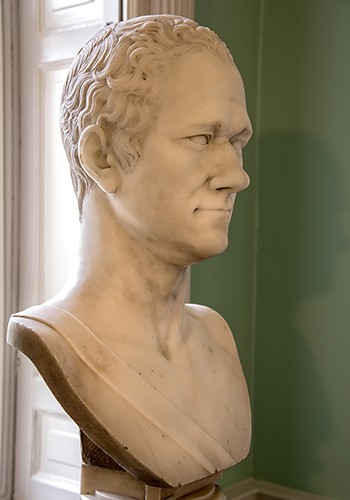

The marble bust of Alexander Hamilton had been sitting in Homewood Museum for several decades, but last summer it sparked a new idea for curator Julie Rose.

While reading Ron Chernow's biography of Hamilton—the book that inspired the hit Broadway show—Rose came across a passage describing a very similar sculpture.

Image caption: Bust of Alexander Hamilton

Image credit: Homewood Museum

In the home of Hamilton's widow, a bust by Italian sculptor Giuseppe Ceracchi portrayed the statesman in "the classic style of a Roman senator," Chernow writes, triggering frequent reveries for the wife who long outlived him: "This was how Eliza wished to recall him: ardent, hopeful, and eternally young."

Making the connection to the Homewood piece—a bust modeled after Ceracchi's original—Rose found inspiration to organize a full exhibit devoted to the Founding Father. Another motivation, she said, was Hamilton's current "star power" due to Lin-Manuel Miranda's wildly original and perpetually sold-out musical.

The resulting exhibit, Alexander Hamilton: The Man Who Made Modern America, is now on view at Homewood Museum through March 11. Chronicling Hamilton's rise from orphaned immigrant to a driving force of American politics, the display incorporates both a national traveling exhibit and artifacts from Johns Hopkins' Special Collections.

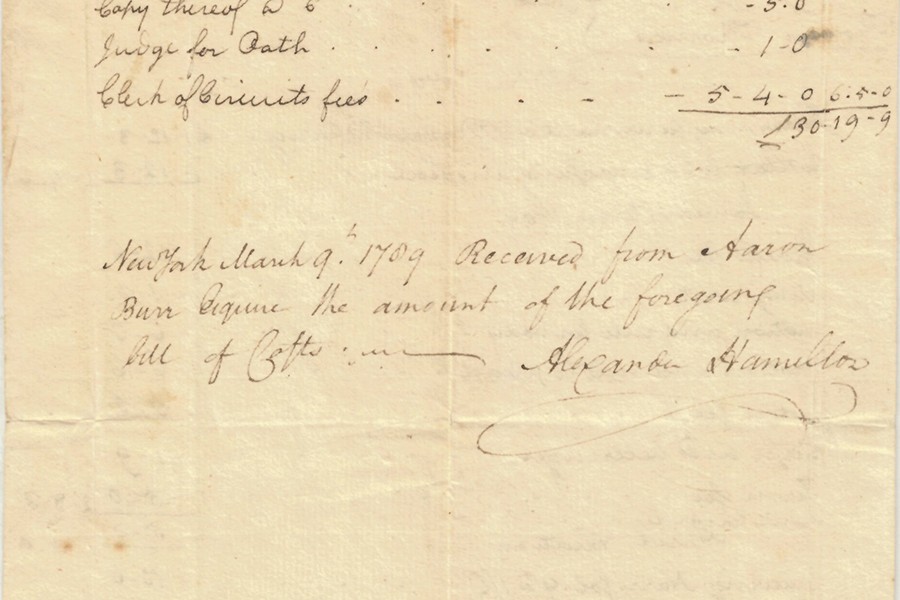

Among the memorable Hopkins finds: A receipt Hamilton logged in 1799, referencing the man who would ultimately be responsible for his death. Writing in feathered quill, Hamilton noted payment of 120 pounds from Aaron Burr for Hamilton's legal services during a two-year court case.

Of course, the relationship between the two politicians later frayed beyond repair, with Hamilton's defamation of the vice president's character culminating in the 1804 duel that left the former mortally wounded.

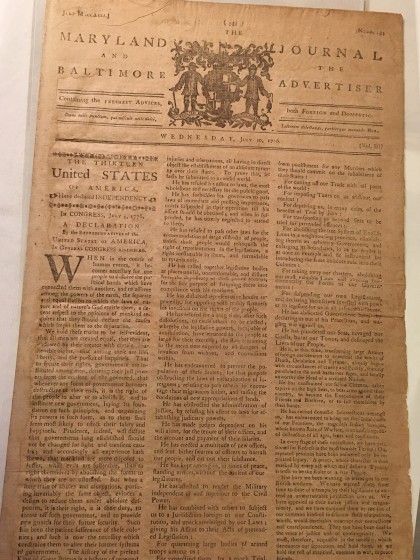

Image caption: This edition of the Maryland Journal, dated July 10, 1776, ran the full text of the Declaration of Independence

Image credit: Homewood Museum

Though that notorious duel remains the most enduring Hamilton reference point in present day—along with his image on the 10-dollar bill—the Homewood exhibit presents a full narrative of his life, from his birth in the British West Indies to his Revolutionary War career and later appointment as the first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury. Also included are details of Hamilton's marriage and personal life, and highlights of his lesser-known work, like efforts to promote education for African-Americans and Native Americans.

From the Hopkins collections, the exhibit includes 16th- and 17th-century philosophy books of the kind Hamilton studied as a boy—writings by John Locke, Thomas Hobbes, and others that fueled his budding intellect. Working as a young clerk in St. Croix, Hamilton so stood out that his boss funded his education in America at King's College (later Columbia University).

Another text on view is a 1787 copy of The Federalist, the influential collection of essays that promoted ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Of the three authors, along with James Madison and John Jay, Hamilton is considered the chief architect, responsible for 51 of the 85 essays.

Elsewhere, a collection of coins from the early 1800s helps narrate Hamilton's role, as treasurer, in building the nation's early financial system—working in line with his Federalist belief in establishing a stronger central government.

The finds from Johns Hopkins help supplement the exhibit's core of text and photo panels, a traveling display organized by the New-York Historical Society, the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, and the American Library Association.

"Alexander Hamilton: The Man Who Made Modern America," remains on view through March 11 at Homewood Museum at Johns Hopkins University's Homewood campus. The display is on view from 11 a.m.–4 p.m. Tuesday to Friday and from noon–4 p.m. on weekends.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Politics+Society

Tagged exhibits, homewood museum, american history