In the classroom, a student complaining about having trouble breathing can turn into a health emergency in a heartbeat.

But for students enrolled in KIPP Baltimore, a public charter elementary and middle school, a quick trip to the school-based health center allows them to be treated on site as they would at a doctor's office, keeping them out of the emergency room and in their seats so they can learn.

That's because KIPP is home to the Rales Health Center, a Johns Hopkins-administered program combining traditional school health services with an enhanced model that includes services such as checkups, sports physicals, immunizations, treatment of acute illnesses and injuries, and prescription medication delivery.

"The school-based health center is essentially like a pediatrician's office that's located right here in the school," says Kate Connor, medical director of the Rales Center and a member of the Division of General Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine at the Johns Hopkins Children's Center. "Any student can access the school nurses, but those enrolled in the school-based health clinic have access to more services."

Take Sherrell Savage's son Ben, for example. He began feeling itchy and told his teacher he was having trouble breathing. At the Rales Health Center, he was examined and treated, and he even returned to class once the symptoms of his sudden allergic reaction had subsided.

The staff at the clinic helped his mother connect with an allergist and ensured that the prescription medications he needed would be delivered to the school the same day.

For his mom, that level of care and attention meant a lot.

"It was scary," says Savage, who at the time worked at KIPP as the director of community engagement. "But when I went down to the health suite, they helped me understand the medicines he would need to take and helped me arrange for the delivery of his prescription. We did a follow-up with the health center the next morning—the way you would with your primary doctor—to see how he did overnight. It was like a full service doctor's appointment, but he didn't miss school, and I didn't miss work."

Image caption: The nurses at the Rales Center form a tight-knit team to manage the workload—which has included more than 35,000 school nurse visits. From left: Katherine Bissett, nurse; Nasreen Bahreman, nurse; Tresa Schumann, pediatric nurse practitioner; and Kate Connor, medical director.

The Rales Health Center employs Johns Hopkins nurses to staff the school health services branch in addition to the physician, nurse practitioner, medical office assistant, and family advocate who staff the clinic. The dedicated team strives to integrate their care with the care provided by the child's primary care physician in a way that's as seamless as possible for parents.

"We work closely together, but there are some important reasons why the functions are separate," Connor says.

Image caption: Teresa Bailey, affectionately known as Nurse Bailey to the students, is the center’s medical assistant and one-woman welcome party who manages the influx of students dropping by for routine or acute care.

The main reason is privacy laws, she says. School nursing is an educational service provided to public school students and is protected under FERPA, the educational privacy law. The clinic provides traditional HIPAA-protected health care, which requires different privacy standards and practices.

Still, says Connor, they operate as a team.

"Our model has built a really robust school health services and wellness program," Connor says. "And we have the advantage of getting to know these kids well. We're able to screen them to determine who needs access to the higher level of care the school provides."

The program, now in its third year, serves the populations at KIPP Baltimore, which is made up of KIPP Harmony Academy Elementary School, and the middle school, KIPP Ujima Village Academy. The schools, which are housed together in a building off of Greenspring Avenue in North Baltimore, predominantly serve the nearby southern Park Heights neighborhood, although they have students from neighborhoods across the city.

Image caption: In addition to providing the school with health care services, the Rales Center also spearheads a wellness program with onsite direction by Ryan Connor (right). Wilnett Dawodu (left) is the center’s family advocate.

The success of the Rales Center represents a positive departure from recent trends in public school nursing, which has yet to recover from steep budget and staff cuts made in the early 2000s. According to a white paper published by the National Association of School Nurses, one in four schools across the country do not employ a school nurse, and another 35 percent of schools employ a nurse only part-time.

On-site health professionals are particularly important in parts of Baltimore City, where rates of chronic conditions such as asthma are more than twice the national average. The Baltimore City Health Department reports that the city's pediatric asthma hospitalization rate is the highest in Maryland and one of the highest in the U.S.

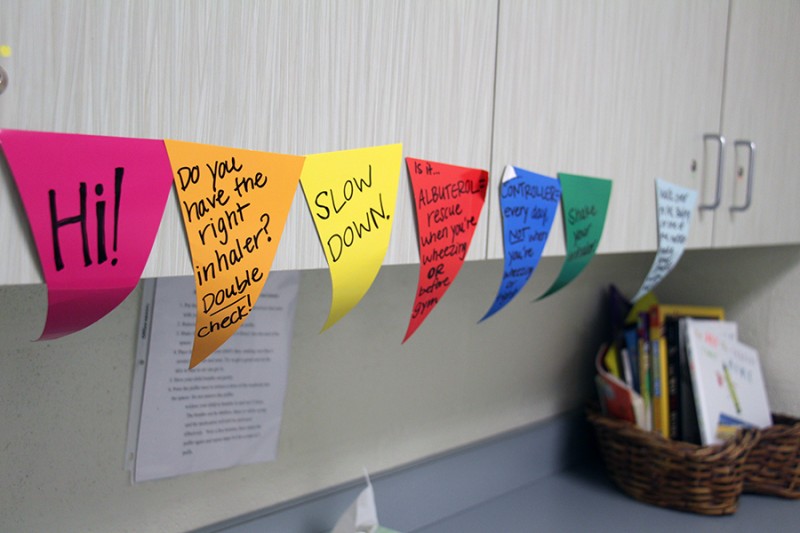

At the Rales Center, students drop in throughout the day to use their daily asthma controller medications under nurse supervision. The center also provides students with spacers, plastic attachment devices that help deliver the aerosol medication. An over-the-door hanging organizer holds dozens of plastic containers storing inhalers and spacers, each container labeled by name. The students have additional inhalers and spacers that they keep at home—which cuts down on the chances they'll accidentally forget their medication.

On their way out the door after each visit, the KIPP kids will typically grab a bag of honeydew from a refrigerator in the corner of the office. Or snag a hug from one of the nurses.

Of the more than 1,500 students enrolled at KIPP Baltimore, nearly 70 percent are enrolled in the Rales Center's school-based health center. Since opening, the center has received more than 35,000 school nurse visits. The program has diverted more than 150 emergency room visits; conducted more than 3,000 screenings for body-mass index, vision, or asthma; and provided more than 100 in-school optometry exams and 200 pairs of glasses.

The center was founded in 2014 by the Norman and Ruth Rales Foundation, which is dedicated to providing children and families from low-income backgrounds with opportunities to thrive through enhanced education, health, and social services. The foundation provided a $5 million, five-year gift to the Ruth and Norman Rales Center for the Integration of Health and Education, the academic home for the project, to pilot the Rales Educational and Health Advancement of Youth model at KIPP. The Ruth and Norman Rales Center for the Integration of Health and Education is housed in the Johns Hopkins Children's Center.

At the start of each school year, the staff at the Rales Center begin their parent outreach and student recruitment, but they allow students to enroll in the school-based health clinic throughout the year. Sherrell Savage, who now volunteers at the school, assisted in the parent outreach on behalf of the health center, and says she plans to continue to tell others about her experiences with the health center.

"The Rales Center has been an amazing benefit for me and my family," she says. "When they opened, they were very intentional about getting to know the students just as young people first and building relationships with students and their families, and then figuring out the best treatment for them. When my kids walk in there, they know the nurses, and the nurses all know them by name. The parents—and the kids—are the best ambassadors for this program."