In a small New Mexico town called Truth or Consequences, a pair of homeschooled brothers are on the hunt for extraterrestrials.

With their mom and a small group of other families, Caleb, 10, and Corban, 6, scour the scrubby desert ground at the base of nearby Turtle Back Mountain, searching for certain kinds of rocks that could be home to microorganisms so resilient and so tough that they might be able to survive outside their rock hosts and live on other planets or moons.

Image caption: Corban Harland, 6, inspects a rock, looking for the telltale green haze that indicates the presence of microbes called extremophiles

Image credit: Darci J. Harland

These citizen scientists were deputized by Johns Hopkins biologist Jocelyne DiRuggiero—who specializes in astrobiology, or the study of the origins, evolution, and distribution of life in the universe—through her crowdsourcing research project, Rockiology. DiRuggiero believes that rocks in deserts and other extreme locations around the world could be home to single-cell microbes that may shed light on whether life could exist outside of our planet.

After all, suggests DiRuggiero, the cosmos is too vast and too crowded with the hundreds of billions or perhaps trillions of galaxies filled with stars and planets for there not to be life out there somewhere.

But the hunt begins at home.

To learn more about these microbes, named extremophiles for the extreme conditions in which they live, DiRuggiero needs to collect samples. To gather those samples, she needs help reaching the most dry, barren places on Earth: deserts, dry valleys in Antarctica, places that resemble other planets.

"We can go to some places and collect rocks, but we can't go everywhere," said DiRuggiero, an associate research professor in the Department of Biology in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences. "We try to be creative and conserve resources."

That's where sleuths like Caleb, Corban, and their mom, Darci J. Harland, come in. While scouting for home-school projects, Harland came across the Rockiology website, which features instructions on what sort of rocks the researchers are seeking, what characteristics to look for, and how to send in photos of the rocks—and perhaps eventually the rocks themselves—along with information on where they were found.

Video credit: Dave Schmelick and Deirdre Hammer

"I've always enjoyed getting kids out into the field to collect data, not just talking about it," said Harland, who is a former public school science and English teacher and university professor of education. "And what better way to do that than to collect data for an actual scientist who needs your help?"

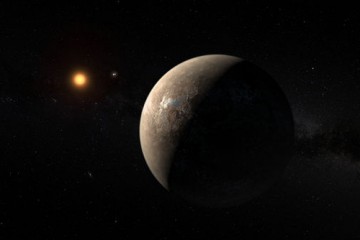

Locations that are potentially rich with extremophile-housing rocks are very dry, very salty, or both. The Atacama desert in Chile, for instance, with its expanses of desolate, reddish terrain—cracked in some spots, littered with stones in others, and broken with jagged cliffs and rock formations—could easily pass for Mars.

DiRuggiero has conducted several rock-collecting expeditions there, discovering a number of Atacama sodium chloride rocks that have been "colonized," as she likes to put it, by microbes. In the exposed innards of a cracked rock, the colonies give away their position in a faint green haze on the white surface. There the creatures find refuge from the more dry, sunny, and windy conditions in the desert.

Also see

So far Harland, her sons, and other homeschool families have taken basic lessons in rocks, extremophiles, and DiRuggiero's work, and they have embarked on sample-gathering expeditions to Turtle Back Mountain.

"We found some colonization and are working now to upload it all to the Rockiology website," Harland said in an email. "Being able to communicate with the scientist on this project has been very rewarding both for me and for the students. They were careful in their data collection, knowing it was 'for real.'"

Microbes that can live in a salt rock might help a scientist learn something about creatures living in, say, briny water. That could be significant for astrobiologists wondering about the prospect of liquid water on Mars, which could be a sign that the place could support life. If water exists there as a liquid it is likely to be very salty, perhaps toxic.

The hunt goes on for more information about extremophiles, the search party now expanded to include anyone who signs on for citizen Rockiology.

Posted in Science+Technology

Tagged biology, cosmology, astrobiology, outer space