In 1945, Frederick Scott used a nickel to make a phone call to the administration at Johns Hopkins University.

"I called and said, 'Do you let Negroes into your school?" Scott recalled in a 2004 interview. "And they said, 'I don't know, we haven't had anyone apply.'"

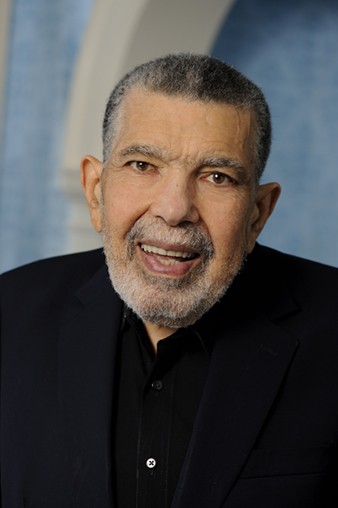

Image caption: Frederick Isadore Scott, Oct. 27, 1927 – July 15, 2017

Scott did apply, and he got in. In February of 1945, he became the first African-American undergraduate student at Johns Hopkins.

On Saturday, Scott passed away at the age of 89. His sister, Patricia Waddy, said he died at The Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore after prolonged health complications.

In his time at the university, Scott was a founding member of Beta Sigma Tau, known to be the area's first interracial fraternity, incorporating members from Loyola University and Morgan State.

He graduated in 1950, after a stint in the Army, with a degree in chemical engineering. Later he pursued a career in publishing and editing for scientific and trade journals, among other pursuits that matched what his friends and family describe as a wide-ranging intellectual curiosity. He returned often to the Johns Hopkins campus, as a popular speaker to alumni and student groups.

Among those mourning his death are members of the Fred Scott Brigade, a Hopkins alumni group that has convened every September for the past two decades, always with Scott attending as the guest of honor.

Scott was not peers with the members of that group—mostly black alumni who attended Hopkins in the late 1960s and early '70s—but they respected him as a trailblazer and honored him by name as a "salute to his life of striving," said the group's founder, Michael Smith.

"He was cutting a path for the people coming behind him," said Ralph Moore, a member of the group who graduated in 1974. "Somebody's got to be first. With each succeeding individual, it gets a bit easier."

In his 2004 interview, Scott was nonchalant in describing his impact on Johns Hopkins, saying his integration on the all-white campus occurred "without a whole lot of fuss."

Video credit: Johns Hopkins University

Nonetheless, he had been aware of the weight upon him as the university's first and only black student. "Oh, boy, that's a lot to carry," he recalled.

Frederick Isadore Scott was born on Oct. 27, 1927, and grew up in West Baltimore with three younger siblings. His father was a postal worker and his mother worked as schoolteacher. His grandfather, Rev. Garnett R. Waller, had been active with the Niagara Movement, which led to the founding of the NAACP.

As Scott recounted in his interview, it was a "smart-ass remark" that led to his entrance to Johns Hopkins. In a conversation with friends one day, he flippantly boasted: "Oh, I can go there if I want to go there."

When his friends scoffed, Scott requested application materials. At the time, he said, he wasn't even well-acquainted with the university.

"You know the name, and you know the campus is somewhere out there, but that part of town was just—you didn't go there," he said.

After taking an entrance exam to secure a scholarship, Scott won admission to Johns Hopkins and started classes on Feb. 1, 1945—just one day after he graduated from Frederick Douglass High School.

"Going one day from an all-black environment to an all-white environment was really a shocker," he recalled in the interview.

Scott attended Hopkins as a streetcar commuter from his parents' home. Aside from the Beta Sigma Tau fraternity—and playing bridge in Levering Hall with a mixed-race group that included Chinese and Jewish students—he described his years at Johns Hopkins as a socially isolated and academically challenging time.

He found a mentor in a black sexton who told him, as Scott recalled: "Don't feel like they're doing you such a big favor, letting you come here. You're doing them as big a favor as they're doing to you."

Also see

Scott took a 15-month hiatus from Hopkins when called to active duty with the U.S. Army in February 1946. He resumed classes the following year, and shortly after married his wife Viola, known as "Vi."

After graduating, Scott worked as an engineer for RCA in New Jersey, then transitioned into publishing and editing. For 40 years he worked for International Scientific Communications, including serving as editor for the American Laboratory journal, according to information provided by his sister.

In his later years, Scott developed an interest in public access television, co-founding the Baltimore Grassroots Media Inc. nonprofit. More recently, he was working on a media project enforcing positive images of African-Americans of all ages, according to members of the Fred Scott Brigade.

Scott and his wife also lived for a time in Blacksburg, Virginia, where they responded to the area's "deficiency in emergency care" by organizing an EMT squad, according to his sister.

The couple spent their last years together in Baltimore, Waddy said, before Viola Fowlkes Scott's death in 2006. In recent years, Scott had lived in Westminster House, a midtown senior community.

Sharon Morris, the director of regional libraries for the Sheridan Libraries at Johns Hopkins, said Scott first came to her attention about 10 years ago when she was working on a history project for the Black Faculty and Staff Association.

The goal of that project—which later developed into the Indispensable Role of Blacks exhibit—was to compile the history of integral African-Americans at Johns Hopkins. When Morris learned of Scott's groundbreaking role, she reached out to get his story.

"Fred was very humble, gentle, and captivating," Morris wrote in an email. "He was patient with our student interviewers, talkative, and had a great sense of humor. What came through was his passion for life, his gentle caring for his wife, and his wide range of interests."

A memorial service will be held at the Providence Baptist Church in Baltimore, located at 1401 Pennsylvania Ave., on Monday, Aug. 7 at 11:30 a.m.

Posted in University News

Tagged obituaries