Writer, farmer, and environmental advocate Wendell Berry says he's "had an easy time of it as a civil disobeyer," evading arrest for the most part throughout his lifetime of activism.

One of the last times he participated in a protest—against mountaintop removal in his home state of Kentucky a few years ago—the governor invited him and fellow activists for a weekend sit-in at the capitol building, where his group made little headway, despite the event's publicity.

"The score between conservationists and the coal industry is 100 to nothing … we haven't got a chance," said Berry, now 82. Yet he still remembers it as one of the best weekends of his life, with bonding among unlikely characters. "A little goodness opened up," he said.

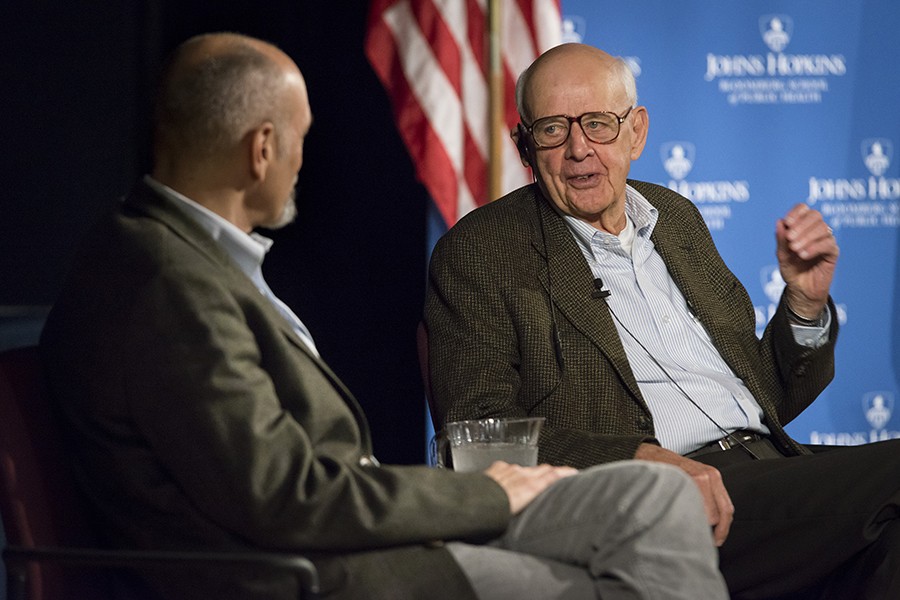

Investigative journalist Eric Schlosser asked why Berry persists in conservation efforts despite acknowledging that he's "on the losing side."

"Well, I just don't want to quit," Berry said.

Schlosser, author of Fast Food Nation, Reefer Madness, and most recently Gods of Metal, sat down with Berry for a conversation Wednesday afternoon at the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health. The event helped celebrate the 20th anniversary of the school's Center for a Livable Future, which studies the relationships between food systems, the global environment, and human health.

Bob Martin, who directs the center's Food System Policy program, called Berry and Schlosser fitting guests, naming their writings among seminal works on food and agriculture.

Berry—who has authored more than 50 works of poetry, essays and fiction—has lived since 1965 with his wife on their farm in Port Royal, Kentucky, near his parents' birthplace.

Image caption: Berry's forthcoming collection of essays, "The World-Ending Fire"

Image credit: Penguin

He touts the virtues of agrarian lifestyles, living off the land, and supporting local economies; and he speaks of the dangers of doing the opposite. In his view, America has tipped toward the undesired state of "the total economy," in which corporations dominate and everything has a price for sale.

Within such a framework, U.S. farmers have become divorced from the food and livestock they're growing, to the point where a dairy farmer must go to the grocery store to buy milk.

"This is insane," Berry said. "How can people take back things they can do for themselves?"

One longtime guiding force for Berry has been the teachings of English botanist Sir Albert Howard, considered a pioneer of the organic farming movement in the 1940s. Howard's writings promote the idea that human farming should imitate nature's growth.

"We've got to study nature," Berry said. "She is a beneficent and bountiful mother, but she's not a very forgiving one. She has punishments."

Schlosser steered the conversation to address the current state of environmental politics and the way rural America expressed itself during the presidential election.

"I'm looking for some hope that this is just a moment and not the beginning, truly, of 'the world-ending fire,'" Schlosser said, referencing the title of Berry's soon-to-be-published book, a collection of his essential writings.

Berry said he wasn't surprised by President-elect Donald Trump's victory.

"The conditions of this election and the Trump triumph have been building up in rural America," he said. "There's these people out there in the country, ... the economy has told them there's no need for them."

However, he described himself as being "on the losing side" of politics, regardless of who leads the country.

"There isn't an agrarian party," Berry said, claiming that "scattered agrarians" are the ones most concerned with the way American land is used.

Though Berry said he believes in the dangers of climate change, he faults the cause for distracting from an even more fundamental philosophy that should guide Americans—"to protect everything worth protecting" and to "stop permanent damage to things worth keeping."

Berry returns today to the Bloomberg School to read his newest essay, "The Thought of Limits in a Prodigal Age." Both of this week's events can be viewed online.

Posted in Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged center for a livable future, farming, environment, writing, food production