Experts in epidemiology and virology gathered Wednesday at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health to discuss Zika virus response in Central and South America and the evidence linking the disease to the abnormally high incidents of microcephaly in Brazil.

The panelists emphasized how little is known of the virus. Colonel Stephen Thomas from the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research estimated that whereas a PubMed search for Dengue virus would return multiple thousands of returns, a Zika virus search would only return one hundred or so research articles, many of which had been published in the 1950s and '60s.

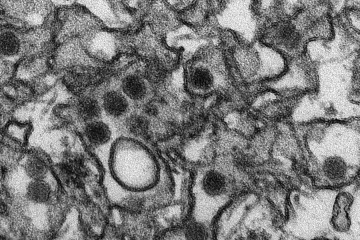

What is known is that Zika is a mosquito-borne illness related to Dengue, West Nile, and Yellow Fever virus. According to the Centers for Disease Control, only 20 percent of Zika cases are accompanied by symptoms, which typically include a fever or rash. The disease has spread to 28 countries and territories, including U.S. territories in the Caribbean.

Also see

But a spike in cases of microcephaly reported in November by Brazil has raised an alarm among public health officials who questioned how the virus affects pregnant women and their unborn children. Thomas Quinn, director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health, said that although Brazil's numbers in the past may have been underreported, national trends show reported cases of microcephaly to be between 139 and 175 each year since 2010. In 2015, that number jumped to 4,074 reported cases.

As of Wednesday, that number has risen to 5,800 cases of microcephaly in Brazil, 3,000 of which are suspected to be related to Zika, said Marcos Espinal, the director of Communicable Diseases and Health Analysis for the Pan American Health Organization.

Watch: Zika virus symposium at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Microcephaly is a fetal outcome where the baby's head is significantly undersized and the development of the brain is limited. Jeanne Sheffield, director of the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, shared a study of 35 infants who exhibited two or more standard deviations in brain or cranial development. MRI scans of the brains of 27 of the infants in the study were made available, and all of them showed abnormalities in their brain development. In all 35 cases, the mothers had lived in or traveled to Zika-endemic areas at some point during their pregnancies, and 74 percent of the mothers reported having a rash during their first or second trimester. Of the 35 infants studied, 71 percent had severe microcephaly with more than three standard deviations in brain or cranial development. These deviations indicate significant abnormalities.

"These are real cases," Sheffield said. "These are ones that make everyone stand up and take notice."

In one case study, the mother began showing Zika symptoms at 13 weeks of pregnancy. Although her ultrasounds at 14 weeks and even 20 weeks of pregnancy showed that her baby had normal brain and cranial development, an ultrasound conducted around the 30-week mark detected brain malformations and extremely calcified portions of the brain and placenta, leading to an in utero diagnosis of microcephaly. After the pregnancy was terminated, an autopsy revealed Zika virus particles in the baby's brain.

Albert Ko, a professor at the Yale School of Public Health, also presented on the fetal cases of microcephaly in areas of the Zika outbreak. His team of researchers began collecting data on Dec. 19 and was able to recruit candidates retroactively, amassing a cohort of more than 700 mother-newborn infant pairs. The team has been working to conduct interviews; gather blood, urine, amniotic fluid, and other fluid samples; and conduct MRI and CT scans of infants where the technology is available.

Results of this study have indicated a prevalence of eye abnormalities and scarring among babies born with microcephaly in endemic areas. Scar tissue on the eyes, Ko said, suggests that an infection or inflammation had occurred in utero and has since scarred over.

"This was actually a surprise to us," he said. "That indicated that [the virus] was affecting [tissues] outside the central nervous system, and also that this may have been a prior infection that occurred and that burned out."

Ko shared a case study of a 20-year-old woman who had normal ultrasounds at 14 weeks and an ultrasound showing few standard deviations at 18 weeks. During her 26-week ultrasound and her 30-week ultrasound, doctors discovered hydranencephaly, wherein the "whole cranial vault was filled with liquid with no residual brain matter," Ko said. She denied having experienced a fever or rash during her pregnancy, but when doctors failed to detect her baby's heartbeat at 32 weeks, the fetal demise was attributed to Zika virus infection.

Even when the mother no longer carries the virus in her blood, physicians have detected Zika in amniotic fluid, which indicates that the fetus has been infected and is urinating the virus out, said Sheffield. (Zika virus has been detected in urine samples of adults long after the virus is no longer carried in the bloodstream, Colonel Thomas reported.) As a result, physicians in endemic areas are offering amniocenteses to evaluate the amniotic fluid for traces of the infection. Though some mothers carry traces of Zika in their breast milk, researchers at this point don't believe the virus is transmitted through breastfeeding.

PAHO and other health organizations have been following the spread of Zika to Colombia, where 35,000 cases have been reported.

"Colombia has a very good laboratory diagnostic platform," Espinal said. "Colombia's going to tell us if this link between microcephaly and Zika is really associated."

The pregnancies of the 2,000 women participating in the Colombian study will reach full term in June.

Posted in Health

Tagged public health, epidemiology, zika virus, microcephaly