Graphic designer Jermaine Bell took the scenic route to his creative career.

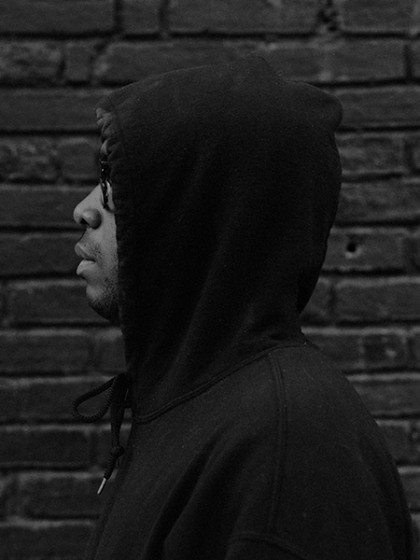

Image caption: Graphic designer Jermaine Bell

Born and raised in Baltimore, Bell tried college for a year in Minneapolis before returning home and working a few entry-level jobs that made him realize he needed to earn a degree. At 24, he put his head down and nose to the grindstone, working at Starbuck's while taking classes at community college before transferring into MICA's undergraduate graphic design program. He continued to work when not in class, adding a gallery assistant internship to his schedule, all while navigating the sometimes frustrating path of being a black student looking to get into a predominantly white field.

Now 32, Bell completed a Greater Baltimore Cultural Alliance fellowship as part the inaugural class of its Urban Arts Leadership Program, and he's currently a Baltimore Corps Fellow and the marketing and program coordinator for Impact Hub Baltimore, the nonprofit innovation lab, business incubator, and community center moving into the Centre Theater in December.

Bell comes to Johns Hopkins University's Homewood campus on Thursday to talk about his career after his journey from community college to MICA as part of the Digital Media Center's Salon Series. The Hub caught up with Bell to talk about why he likes working with smaller nonprofit organizations and the lack of diversity in Baltimore's design and arts communities.

I didn't look up what MICA's undergraduate student demographics are, but I imagine that, like Hopkins, the number of young black students from Baltimore is pretty small. And from talking to a few black Hopkins alums, I get the impression that school can be a little odd—not just being at a predominantly white institution in a predominantly African-American city, but also because so many people come from elsewhere to go to school here that don't have that sophisticated an understanding of the city's racial makeup at all. What was your MICA experience like? And in addition to providing you with graphic design expertise, did going to MICA inadvertently prepare you for the professional life in an industry that, according to an American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA) professional society report, is about 86 percent white as well?

Yes. At MICA, as a transfer student, your group of friends is the other transfers. Students clearly knew we were not like the other kids that were there. I'm bringing in work on laser printer paper because I'm not spending $20 on Arches stock for a mock-up. And you can feel the eyes judging you.

I'm not a person who breaks down, but I was so physically exhausted and getting frustrated because at school nothing I did was ever what I wanted it to be. And I remember one time I was presenting mock-ups for this project I was doing—it was going beyond the branding of the small things and it was going into the spatial design. I was telling [my class] how I went to the [Hampton] mansion in Towson and I was saying how insane it was that all these rich, beautiful things were inside this castle-like place, and that's how the slave owners lived juxtaposed against the tiny, communal stone cabins slaves were forced to lived in. And because I said "castle," somebody scoffed and said, "There's no castles in Maryland." And I replied, "Oh, that's right—it was a plantation." I had to make everyone uncomfortable to make my point. And from then on you become known as the angry guy.

In another class, I was working on my thesis, Cosby Sweater. And, yes, hindsight is 20/20, OK—this was before we know what we do now. The point was to explore black male identity. I was also working with quotes from A. Philip Randolph and Huey P. Newton. But it was called Cosby Sweater and touched on the positive subliminal messages that were conveyed via the Huxtables. They collected art, they were intellectuals, but they were still human beings when they were in their home. That's what I was writing about and looking at. And I was presenting it in class and some of the only standout feedback from students I got was like, "Oh my god, Cosby sweaters are so fun to wear." And the rest of the class was dead-ass silent. That was the extent of critique that I got from my peers.

The professor, Kristen Spilman, was really great—she was really smart and helped me fine-tune what I was trying to say, but the majority of the class was not into it. And that's what being black in higher education is like. People just assume that everyone has this one path to college—right from mom and dad's house into a four-year college, then you get married in a tuxedo and a white dress, then you buy a house. That's not my life and not the life of a lot of people I know.

Did you find that there's a lack of diversity echo in the field itself when you started working?

I worked in an agency and it was like a frat house. It was Mad Men accelerated to 2013. I had a black female creative director, but the creative staff was only seven people, and I was both the traffic manager—meaning every morning I'm hosting a morning meeting with a spreadsheet saying, "You're going to be on this, you're going to be on that"—and I was a designer, so that was a whole different part of my day. So we would be there 14 hours a day, and people were fine with that because that was their life. But because we were always there, people treated [the office] like it was their home. They would come in there wearing shorts and flip-flops and T-shirts. And we were downtown on Pratt Street, around the corner from The Block, and they're [talking about women's bodies] and I'd be like, "There is a woman right here." And I'm a gay man—and I don't know if they knew that, but I wasn't fitting into their culture, but that's the thing. It didn't matter [to them] if I fit into their culture. Being black and gay, I rarely "fit the culture."

How have you tried to find your place in the field?

I joined the AIGA because people seem to think design is either hand-lettering or it's the opposite. It's, "I wear an apron, have a handlebar mustache, I get my hands dirty, and I'm a screen printer."

But there were two projects that really made me change my opinion about design in general. The first project was the materials I made for my partner, painter Stephen Towns' show co | patriot. Stephen had some shows around town, but no one was taking notice of him. People thought his work was beautiful, but there was no writing about it. So when he started planning his first solo show in Baltimore at Gallery CA, which is a malleable gallery, Stephen, my friend Kirk, and I branded the show. We drafted a press release. We made sure the press packet was tight. We styled [Stephen] for press photos, which he hates. The title, co | patriot, is a play on the word "compatriot," and the show was about the duality of African-American life, our interior and exterior lives. The logo was black and white, and I always used red somewhere in the press materials—everything was mailed out in a white envelope with a little strip of red tape closing it, symbolizing the blood that connects us. I created specific LED billboards for the show. The advertising was so good for the show [the Baltimore LED] asked me to give more images of Stephen's work. We aimed for national press, which we didn't get, but he was written up by almost every publication in the city. And he just won a Ruby [artist award] because of that show and he worked on a Main Street beautification project with Christina Delgado of the Belair-Edison [public art project], and Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake gave a speech and toured the neighborhood. He even the did the official portrait of Bea Gaddy at the Bea Gaddy Family Centers in East Baltimore. We helped bring some light to him and his work and his mission.

I was actually going to ask—and I don't want to sound like I'm being too cynical—since the events of the uprising, of course, there's been a great deal of talk about what goes on in the city and how arts and culture fit into that discussion. How have the events of the uprising and the death of Freddie Gray, mutually exclusive events, impacted how black artists are seen or viewed in the city. Has it?

Let me answer that by talking about the second job that changed my life, working at Hopewell Cancer Support, a nonprofit organization. I was hired just to do an annual fund packet for them. They liked my work so much they asked me to come back. I did their spring 5K run for them, some print work, a newsletter, and helped with their Giving Tuesday campaign. And in the midst of this, because I live in Station North, they asked me to meet with Anelda Peters, who lives in Station North as well. Anelda's husband was [the late Baltimore artist and Station North pioneer] Roy Crosse. Anelda and Roy went [to Hopewell] when Roy was in the last stages of his treatment. He was very thin, could barely hold anything down, but he would go there and do yoga and was part of the team who would help fundraise.

You would think there would be a Roy Crosse plaque somewhere in Station North, right? I hear there's something in the works now. But where was the Roy Crosse memorial when he passed last year? I had no idea how instrumental he was in building he Station North community. He was a beloved pillar of the community. I think seeing Roy's face in bronze would help the morale of so many black kids that walk up and down North Avenue—especially the black MICA students.

Seriously—he moved down here from New Jersey in what? 2001? 2002?

In 2002. I mean, my family is from East and West Baltimore, and back then even they would say, "Hell no we're not going down there." But he built a house there, and he was making beautiful things in that house. He had a koi pond on North Avenue. So has it changed for black artists? Hell no. Once you are famous, yes, people love you. But mostly everyday people are overlooked.

I just wrote a piece about Galerie Myrtis and her work with the producers of [the TV show] Empire for Bmore Art. So there's Galerie Myrtis, New Door Creative Gallery, [Baltimore painter/gallerist] Jeffrey Kent is about to reopen a gallery, Jubilee Arts Center, New Beginnings Barbershop, the Reginald F. Lewis Museum, the Great Blacks in Wax Museum, and the Eubie Blake Cultural Center—those are the black arts spaces in a city that is [about] 64 percent black. And artists can't show at Blacks in Wax. So you have five galleries that you have to try to get into as a black artist. I can name six arts spaces in Station North alone. They may show black artists but they are uncomfortable with the issues surrounding "black art." And look what happened to "Madre Luz," Pablo Machioli's sculpture at the Copy Cat, a seemingly liberal arts hub. Why would any black person want to show there after that? My safety is in jeopardy there. My piece is in jeopardy of vandalism.

Was it the experience with the cancer wellness center that made you want to work exclusively with nonprofits if you can?

Yes. Everything I was doing for them was because I loved the women who worked there. And these are all white women, but we could have deep conversations about the work they're doing in addition to talking about all the design work they needed. And just being in this space with them and having them respect my opinion and what I was doing for them, I went into work [thinking], This place is so dope.

That changed my opinion of what work should be. There was no way I could go back to an agency where we'd get a brief saying we're targeting 40-year-old white men who work out. And, because they didn't want to shoot original photos, I would sort through Getty images—because even though we were going after older white men, we were going to go about it by showing them images of young people. So I'd be sitting there all day looking at skinny white people and the most beloved kind of people in advertising, the racially ambiguous, sitting on the beach drinking beer. That was my whole day as a designer.

So when I left the agency and bounced into these older ladies' offices with papers and people everywhere and they just kept wanting more and more of my work because they liked and respected my work and who I was, I realized that's what was missing in design for me: being a human being. Instead, it often feels like it's all about a product. People are products now, and design is just helping to facilitate that. In school, you think you're learning all these concepts and tools to be a better designer, but when you're out in the real world, all they want to do is sell product.

That's why I'm here at the Impact Hub. I know there are a lot of things people can say about Station North being gentrified, but if I'm in a position where I can help put people of color or people who are not ever used in campaigns in projects that might make them feel like they're valuable, I want to be that gateway.

Posted in Voices+Opinion

Tagged visual art, digital media center, art