Contrary to assumptions that disadvantaged neighborhoods trap children in failing schools, a Johns Hopkins University sociologist has found that as a neighborhood's income decreases, its range of educational experiences greatly expands.

Julia Burdick-Will found it was actually children in affluent neighborhoods who stayed close to home for school. In lower-income neighborhoods, kids in search of better options dispersed to dozens of other schools, often commuting alone for miles.

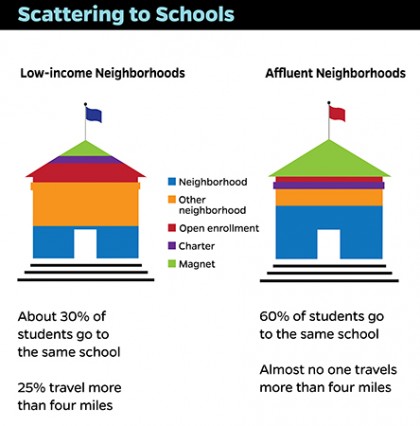

In Chicago neighborhoods with a median household income of more than $75,000, most students attended one of two or three schools. But when the neighborhood median income dropped to less than $25,000, students dispersed to an average of 13 different schools.

"We clearly show that the belief that where one lives determines where one goes to school isn't the reality in Chicago or in an increasing number of U.S. cities," Burdick-Will said. "You have kids scattering everywhere."

Burdick-Will, an assistant professor in JHU's Krieger School of Arts and Sciences and the School of Education, presented her findings at the recent American Sociological Association annual meeting. The conclusions have implications for inequality and social mobility, particularly as nontraditional school choice options like charter schools and open enrollment continue to increase nationwide.

"We think of children in poor neighborhoods as 'stuck.' But they're not stuck in one geographic place," she said. "They're stuck navigating a complicated and far-flung school system."

Burdick-Will examined administrative records for more than 24,000 Chicago Public Schools eighth-graders entering high school in the fall of 2009. The freshmen attended 122 high schools, including standard neighborhood schools that admit students from outside the neighborhood when they are underenrolled, open enrollment schools, charter schools, and magnet schools.

While just over half the students attended a neighborhood school, one-third of them weren't attending their neighborhood school.

Essentially no one in higher-income neighborhoods attended open enrollment schools or charter schools, but in disadvantaged areas, more than 20 percent of students attended open enrollment schools and another 7 percent chose charter schools.

And the low-income students endured the longest commutes to school.

In affluent neighborhoods, almost no one traveled 4 miles to school; the average commute was about 1.7 miles. But in disadvantaged neighborhoods, the average commute for children was 2.7 miles, with 25 percent of the kids traveling more than 4 miles. Ten percent of the low-income kids traveled more than 6 miles.

Burdick-Will found that a student in a disadvantaged neighborhood was also 35 percent more likely to be the only person from their neighborhood at school.

In low-income neighborhoods the problem isn't just access, Burdick-Will said, but the potential social costs of traveling far across the city every day, possibly alone—costs that don't apply to similarly achieving students in higher income neighborhoods.

"We think of choice as a thing of privilege," she said. "But what we see is that there is a privilege of not having to choose."

Posted in Politics+Society