Ten years after Hurricane Katrina barreled into the Gulf Coast region, New Orleans is still contending with its aftermath, and the nation is still wrestling with the economic, political, and racial disparities in American cities that the disaster forced into light.

Whatever the issue—whether crises in housing or the unequal distribution of redevelopment investment—the inconvenient fact is that to this day, African-Americans have endured the brunt of Katrina's lasting turmoil, so much so that the storm and its disastrous aftermath can be viewed as the catalyst for a new wave of black protests, as evidenced by the Black Lives Matter movement.

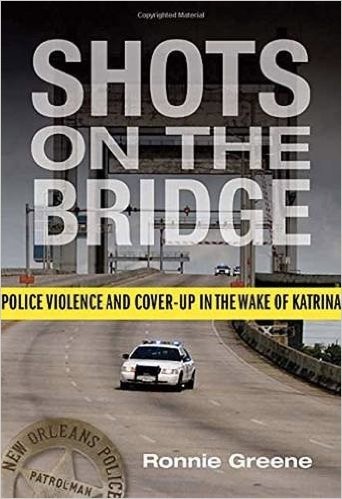

With his new book, Shots on the Bridge (Beacon Press), Associated Press investigative journalist Ronnie Greene—a 2013 graduate of, and now science writing faculty member in, the Johns Hopkins Advanced Academic Programs writing program—zeros in on a Katrina case that highlights another pressing contemporary issue: police brutality.

Subtitled Police Violence and Cover-Up in the Wake of Katrina, Greene's book examines a shocking incident that took place on the morning of Sept. 4, 2005, six days after Katrina made landfall. Two New Orleans families, both African-American, were crossing the city's Danziger Bridge that day when a group of armed men spilled out of a Budget rental truck and began firing on them. When the shooting stopped, two of the unarmed civilians were dead and four others were wounded. (This Times-Picayune graphic provides a detailed timeline of the shooting.)

The men were plainclothes members of the New Orleans Police Department who had responded to an officer-in-distress call. Some of them almost immediately began making plans to cover up what happened, claiming they saw a gun and responded with appropriate force to a life-threatening situation, then inventing witnesses who could attest to those facts. It took a few years for a federal investigation to indict, try, and convict five officers involved, but the presiding judge vacated the guilty verdict. Last week, the five New Orleans police officers were granted a retrial.

Greene says he first came across the Danziger case in the fall of 2011. Earlier that year, he and his wife moved to the Washington, D.C., area when he started working for the Center for Public Integrity—he was a project editor on its Breathless and Burdened series, in which reporter Chris Hamby details how the coal industry's lawyers and doctors denied miners' black lung claims; the series was awarded the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting. Greene knew he wanted to write another book. His first, Night Fire: Big Oil, Poison Air, and Margie Richard's Fight to Save Her Town, followed one woman's grassroots fight against the giant Shell Oil Company after a chemical plant explosion in her small Louisiana town, a years-long journey that took Margie Richard from schoolteacher to environmental activist. So Greene understood the twists and turns a fight for justice often involves. He started looking into the Danziger case around the time he began graduate school at Johns Hopkins.

Shots, recently excerpted at Al-Jazeera America, is a bracingly disquieting read. In fewer than 300 pages, Greene explores why these two families stayed behind, how they ended up on that bridge that morning, the NOPD's history of violence, the disorganized state of New Orleans law enforcement during and after Katrina, and the fallout of that terrible morning on the bridge. Greene will discuss the book, which has received favorable reviews from NPR and The Times-Picayune, during a taped C-SPAN2 interview scheduled to air Saturday night at 7:30 p.m.

The Hub caught up with Greene by phone to talk about investigating police brutality cases, the culture in which such corruption takes place, and the difficulty of seeking justice when cops are the defendants.

In your notes about the research, you say you were first drawn to the case when you saw an AP story about it in August 2011 and knew it would make a good book. What was it about this story that attracted you to it? This is before Judge Kurt Englehardt reversed the decision, so what about the story at that moment drew you to it?

There was one afternoon where I was just looking at the wires and I saw a story out of New Orleans about the conviction of the officers in this really tragic, painful event that occurred just days after Katrina. There were so many abuses during and after Katrina, this was the first time I had seen a story set just on this case. I took a few minutes to read this story and it was a very moving piece because it had information about the victims who were on the bridge, including Ronald Madison, a 40-year-old man with the mental development of a 6-year-old, who had been shot on the bridge. And something about reading that story, I just knew instantly that this was a book. My initial thought was, to the best extent that I can, to stop time, to get a sense of who were the residents on the bridge, who were the officers on the bridge, and how did they get there. Why was everyone still in New Orleans? How did they get to the bridge that day? To call it a tragedy is an understatement. I just knew at that moment that this was worthy of a deep exploration.

How did you start? And I ask because in your notes you talk about the mammoth trove of documents and transcripts and interviews you went through. Did you start by going through initial news reports to get a sense of the timeline? Where do you start putting together something that seems even at first blush fairly complex? And I'm sure the first few layers you unpeeled led you to even more complexities than that.

My instinct told me that this was such a meaningful story to pursue, but when you're trying to work on a nonfiction book there's no guarantee that your hope for a book will become a book. So the way I look at it is you have to do enough research to really have your arms around the subjects enough that you feel you can put together a compelling proposal, knowing that that's just the beginning of the research. So my next steps were trying to do that, to put my arms around what's going on. I had read a bit of the clips, and I had seen some of the lawsuits filed by family of the victims on the bridge. I started pulling up some of those lawsuits and reading the narrative backstories. And this was still early on, I was doing it nights and weekends, apart from my day job and grad school. And then in April 2012 was the sentencing of the officers; the four shooters on the bridge and one supervisor who went to trial were sentenced in New Orleans. I flew down to New Orleans to cover the sentencing, just to get a fuller sense of the story. I went from there and just kept reporting and reporting until I felt like I had my arms around the key elements of what happened.

In the research process, were there any surprises? As in, did you come across something that you didn't expect to give you an insight or a new perspective on the case?

The thing that kept striking me in researching this over a period of three years was how much there was to learn. I felt like every time I looked into one element of the story I was learning something new, whether it was about the officers and the people on the bridge and how they had gotten there that day, whether it was about the history of the New Orleans Police Department and its civil rights cases that go back decades. Learning about the terror and the trauma of Katrina in New Orleans. And, of course, learning about what happened in the case from the sentencing forward—I felt like every time I looked into one element I was learning something else.

Let me give you one example. There were so many tumultuous moments in this story, from the hurricane coming in until that fateful morning, Sunday, Sept. 4. It was almost so much tragedy to take in you couldn't take it all in at once. One of the things I did later on in the reporting was get the transcript of the trial that played out over several weeks in the New Orleans summer of 2011. I read the entire transcript, and every time I read that transcript I learned something new. One of the families that was on the bridge was the Bartholomew family. A mother and a father, they had three children with them, and they had one of their nephews and their nephew's friend. That morning, the mother and father, two of the kids, and the nephew and the nephew's friend were heading out from the decrepit hotel they were staying in. They were trying to get to a store to get some cleaning supplies for the hotel, and also to get some medicine.

The Bartholomew family had stayed in New Orleans because Susan Bartholomew, the mother, had just one van and there were 10 or 11 family members needing to get out. The van's not big enough to take everyone. And she made the decision, "If we all can't go, we're all going to stay." That's why they stayed.

And on the bridge, Susan's arm was shot off, her husband was hit by shrapnel in the head. Her 17-year-old daughter, Lesha, was down by her mother and literally laid on top of her mother trying to protect her as the bullets kept coming. Their nephew, José Holmes, was shot in multiple parts of his body and barely survived. And José's friend, 17-year-old James Brissette, was killed. And the youngest son that was with them is Leonard Bartholomew IV—Little Leonard, they called him, because his dad was Big Leonard.

There's so much tragedy here—the mother's lost her arm, her daughter's trying to save her mother's life in this heroic moment of lying on top of her—that in a way I lost track of Little Leonard. And as I looked into this much later I found that Little Leonard [who was 14 at the time] ultimately was taken in by a stranger and went up to Baton Rouge for a couple of weeks. This stranger, a great Samaritan, took him in, put a notice on the Internet, and one of Leonard's relatives from Texas saw the notice, came to Louisiana, picked him up, and they went instantly to the hospital. This was weeks after the shootings. Little Leonard had no idea what was going on with his family, and his mom, Susan, woke up with no idea where her son was. So Leonard goes to the hospital, sees his mom in a hospital bed and her arm is amputated. He sees his sister in a hospital bed; she can't walk. He sees his cousin, José Holmes, who is like a brother to him, he's in a hospital bed and he can't even talk. He can barely move. And suddenly this teenage boy, who escaped only because an officer fired two shots at his back and missed both times—he looked at his cousin José and basically said, Why wasn't I shot, too?

That moment just really hit me and I didn't get into that moment until years into the research because there were so many things to learn and so many painful, poignant moments that it took me forever.

That leads me a bit into my next question: You're looking at one case, and you're never going to know everything about it, but you do have the luxury of some time and distance from it to pore over it. Did going through this singular case, trying to get a sense of what happened—from Katrina and its immediate aftermath, through the shooting on the bridge, and up to and after sentencing—give you any sense of things journalists should be asking when they're in the midst of reporting a police brutality or corruption case? Did writing this give you any insight into ways to cover or questions to ask when a similar kind of case is ongoing?

I can answer that in two ways. One of them is that while I really focused on those moments on the bridge, it was important to understand those moments in context of the New Orleans Police Department's history. So I went back several decades and looked at some of the really infamous cases of police abuse against unarmed citizens. There are several cases where that happened. One New Orleans female police officer is on death row today. And the Danziger shooting is not the only tragic police shooting after Katrina. The other case, [which took place] just within days of the Danziger shooting and [which] also got a great deal of attention, is the Henry Glover case. There have been cases since. And after these events, the Department of Justice did a really detailed investigation, looking at the current history of civil rights abuses by the New Orleans police, with some really striking findings. So I spent a lot of time looking at those moments on the bridge, but I had to go backward and forward to understand it in context. That would be my advice to researchers—this case is the spine of what I'm looking at, but it fits into a larger story, and that's what I tried to do.

Another thing I would say is keep an eye out for the culture of the department. In this case, there was a cover-up that was starting to be put in play right on the bridge before the paramedics took everyone away. That was laid out in testimony at the trial. One of the people I interviewed is the former mayor of New Orleans and the head of the National Urban League, Marc Morial, who had a very keen interest in this case because of his ties to New Orleans and his current role now. And he said, and I'm paraphrasing, but basically if the police department has corrupt practices, those kick in right away. And I think there's evidence of those kicking in right away here.

I wanted to ask you about that bigger context, because you do a compelling job of providing a background of the New Orleans PD's problematic history and touching on the culture in which corruption takes place. Did your own investigation lead to an understanding of how those things develop and persist? You allude to some things—reform-minded leadership that isn't in place for a long time, court systems that don't punish this behavior when it actually gets to court. I realize you can't make broad, sweeping generalizations from one case, but did having to take a deep dive into this culture and department offer some indications of how these issues develop over time?

One of the things I heard, and I heard this from a former police officer in New Orleans who spent many years patrolling the urban core who is now a lawyer for police, and I heard this from Marc Morial and others, is that it really starts at the top. I don't want to sound cliché, but it starts at the top, from the mayor's office down. Who the mayor picks as his or her police chief really makes a huge difference. I talked to a number of civil lawyers in New Orleans and police watchdogs, and Marc Morial, when he was the mayor, appointed an outsider, a man from D.C. who wasn't friends with officers and came in and, apparently, had a focus of weeding out real corruption. The mayor of New Orleans at the time [of the Danziger shooting] was Ray Nagin, who had not had prior political experience and was a populist mayor who appointed a popular colleague already in the force [to be chief], who was really close with officers. And one thing I heard is, You have to have a culture at the top where the message is sent that these types of abuses will not be tolerated. And I think one thing that struck me when looking at the cover-up is you don't see any sense that the officers involved here were looking over their shoulders at the officers above them. You don't get any sense that there was any pressure from City Hall down to make them go a certain way or not. You didn't see that at all. And I think with a different type of administration, and I'm getting this from multiple different voices, you would see this differently. So the culture starts there, at the top.

I was very impressed by the concision of your storytelling in the book. You're dealing with a wealth of information and you're presenting it tightly. And you do it without trying to add emotion where the facts of the case are doing that for you. And I wanted to ask you to talk a bit about the writing process, because in the past 15 months or so we're seeing a lot more writing about police brutality for obvious reasons, and as much as we see a fair amount of conventional news reporting, we're also seeing a lot of emotionally powered storytelling. There's room for both, but this strikes me as a story where you don't need to add for the emotional weight of it, and the severity of that emotion, to land.

One of the things I always try to say as a reporter and editor, and this would apply to any deep dive, the story is the star, the writer is not the star. What happened on that bridge—the events leading up to it, what happened, and the events after it—was profound, and I didn't need to put anything extra in it. The best thing that I could do is tell the story and get out of the way. Let the story tell itself. My wife essentially told me that when she read some very early drafts, and she was so right. So my challenge as a writer was to gather as much information as possible. Try to keep an eye out for details that are telling or revealing. Learn as much as I could about the people and the place. I drove up and down that bridge so many times just to get a sense of it, and I retraced the steps of everyone as best as I could. But all of that was geared toward letting the story tell itself because, you're right, it didn't need anything more than that. The story is powerful enough that it carries itself.

I wanted to ask because I wanted to know if you have any advice for reporters following similar situations or even cities that are in the grips of watching a case like this play out, because we're now 10 years down the line from this and the case is still in the system and, for many people involved, it has yet to come to a resolution.

That's really one of the striking things to me, to be honest with you. The residents on that bridge were completely innocent. There was one family we talked about; they stayed behind because they had one van. The other family, the Madison brothers, Ronald and Lance, stayed behind because Ronald didn't want to leave his dogs. They were both driven away from their homes by the storm. Each family was on the rooftop waiting and pleading for help. And each [family] that day was just trying to survive. One family was trying to get to Winn-Dixie. The Madison brothers were trying to get back to their family house not far from where they were staying at their brother's dental office, essentially to get on bikes and pedal away. They couldn't get there, so by nature and fate they were drawn together on that bridge the moment that the police raced out. They were good families, good citizens, just trying to survive. They did nothing wrong, yet it's been 10 years and the [case] is still unsettled. That speaks for itself on the difficult road for justice—and experts will tell you this—when officers are on the other side as the accused.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Politics+Society

Tagged books, advanced academic programs, police, writing