Howard W. Jones Jr., a pioneer in reproductive medicine who oversaw the 1965 Johns Hopkins research that resulted in the world's first successful fertilization of a human egg outside the body, then collaborated with his wife—gynecologic endocrinologist Georgeanna Seegar Jones—to oversee the 1981 birth of the first "test tube" baby in the United States, died Friday at Sentara Heart Hospital in Virginia. He was 104.

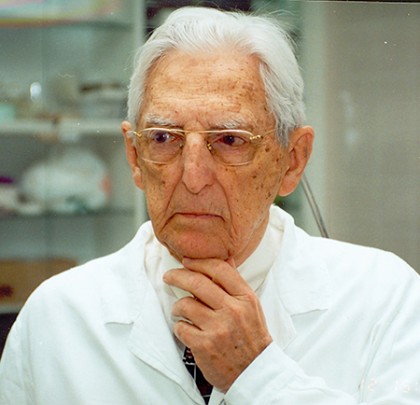

Image caption: Howard W. Jones Jr.

Image credit: Johns Hopkins Medicine

Jones had published his most recent book, In Vitro Fertilization Comes to America: Memoir of a Medical Breakthrough, just last year.

In recent years, Jones also became known for having been the first physician at Johns Hopkins to examine Henrietta Lacks, the 1951 African-American patient with cervical cancer whose tumor cells—classified by researchers as HeLa, using the initial letters of her first and last names—were the first human cell line to reproduce continuously in the laboratory, becoming the basis for studies that have led to some of the most crucial medical advances of the past 65 years.

"Johns Hopkins has lost one of our true giants—as has the entire world of medicine and gynecology in particular," says Paul B. Rothman, dean of the medical faculty and CEO of Johns Hopkins Medicine.

"Dr. Jones was one of the most remarkable individuals I've ever known—with a razor-sharp mind, memory, and perspective that would be the envy of anyone half, or a quarter, of his age," Rothman adds. "His great wit, insight, and humility were well on display when he was here less than a year ago for the dedication of the Howard W. Jones Jr., M.D., and Georgeanna Seegar Jones, M.D., Professorship in the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, at which I was honored to preside. He was a great humanitarian as well as a groundbreaking physician, and we will miss his wise counsel."

Also see: Howard W. Jones Jr., a pioneer of reproductive medicine, dies at 104 (The New York Times)

Added Andrew J. Satin, director of the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at Johns Hopkins Medicine: "Howard Jones was an extraordinary man who, even in his final days, was a key contributor both academically and philanthropically to innovation and discovery in the field of reproductive health. I am honored to have had the incredible opportunity to have met with and corresponded with this legend in our field."

As accomplished as Jones was in the operating room and laboratory, he was also revered as a teacher and mentor who influenced generations of Johns Hopkins medical students. One such physician, Robert D. Chessin, a 1973 graduate of the School of Medicine, recalls going on rounds with Jones and the impact that has had on him ever since.

"The care and respect he displayed with all patients, from the richest people in town to the poorest East Baltimorean, is something I will never forget," says Chessin, a longtime pediatrician in Fairfield, Connecticut.

"He used to ask their permission before he would go ahead and examine them. It always has reminded me never to take examining a patient for granted, that the patient is allowing you to lay hands on them, that it really is a privilege to do so."

Jones was born on Dec. 30, 1910, in Baltimore, the son of a physician. After graduating from Amherst College in 1931, he entered the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Following his graduation from Johns Hopkins, Jones completed his internship and residency in general surgery while working for both Howard Kelly and Kelly's successor as head of Johns Hopkins gynecology, Thomas S. Cullen.

During World War II, he joined the Army and served as a general battlefield surgeon with General George S. Patton Jr.'s Third Army as it fought its way across France and Germany.

Returning to Johns Hopkins following the war, Jones spent six months as a resident in gynecology. He and his wife joined the Johns Hopkins part-time faculty in 1948, maintaining private practices while working at the hospital, and became full-time faculty in 1960.

Jones' work with in vitro fertilization began in 1965, when he helped arrange for British scientist Robert Edwards to come to Johns Hopkins as a fellow to conduct experiments aimed at achieving the first fertilization of a human egg outside of the body, in vitro—or in a medium in a petri dish—something he already had accomplished with mice. Working together and with others, Jones and Edwards succeeded but didn't realize it at the time. Because the criteria for in vitro fertilization of an egg then were different from what later was established, they only reported on their efforts at "attempted" in vitro fertilization (IVF). Years later, examining their study in the wake of subsequent developments, they recognized that they actually had done it.

Due to Johns Hopkins' policy in 1978 of requiring faculty to retire at 65, the Joneses left Baltimore that year and moved to Norfolk at the invitation of Mason Andrews, head of gynecology at the then new Eastern Virginia Medical School. The Joneses arrived in Norfolk on the same day that the first "test tube" baby in Britain was born, and soon established the Jones Institute of Reproductive Medicine. Their efforts succeeded three years later in the birth of the first "test tube" baby in the United States.

Jones also was a pioneer in performing operations on intersexual patients, such as genetic females born with male genitalia. He and other Johns Hopkins specialists eventually co-authored a major text on such cases, Hermaphroditism and Allied Disorders. He also performed some of the first sex change operations for transsexuals.

Jones retired from his medical practice in 2000 to care for his wife, who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease. She died in 2005 at the age of 92.

Although he gave up seeing patients in recent years, Jones continued going to his office at the Jones Institute almost every day, writing papers and books in longhand. He credited his longevity to a wonderful marriage, excellent family life, and a determination to keep working. "The simple message for longevity: Do not retire from intellectual pursuits," he said shortly before his 104th birthday.

"Howard Jones was a devotee of Johns Hopkins for more than 80 years, and he returned annually from 1984 to 2014 to attend and participate in the lectureship that honored him and his wife, Georgeanna," says Edward Wallach, University Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "He will forever be admired as a mentor and for having a profound influence on his trainees and younger colleagues, including me."

Jones is survived by three children—Howard W. Jones III, the chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Vanderbilt; Georgeanna Jones Klingensmith, a professor of pediatrics and former director of the Barbara Davis Diabetes Center at the University of Colorado; and Lawrence Jones, also a physician, both of Denver, Colorado—seven grandchildren, and 14 great-grandchildren.

Posted in Health

Tagged henrietta lacks, obituaries, reproductive health