Psychiatrist Jennifer Coughlin could hear the worry in the voices of the retired NFL players who volunteered to participate in her study of concussions. They were concerned about their mental health, about the potential consequences of the hits they had weathered throughout their careers.

Image credit: Illustration by Brian Stauffer

"A lot of questions remain, so they have a lot of anxiety and fear of the unknown," says Coughlin, an assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. "They asked us if playing certain positions put them more at risk for brain injury, and at what age the brain begins to show signs of inflammation. Many high-profile players have had significant issues with memory, and we've seen some cases of suicide from depression."

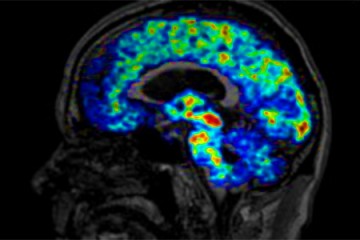

Media reports of such suffering among former football players and their families have driven researchers nationwide to study the long-term neurological impact of contact sports such as football, ice hockey, and lacrosse. Many are trying to determine whether athletes are at risk of developing chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE—a degenerative disease associated with memory issues and possibly dementia—but the drawback is that it can be diagnosed only after death, by autopsy. Coughlin's team of psychiatrists, radiologists, and nuclear medicine specialists took a different tack. They used positron emission tomography, or PET, scans with a brain-injury biomarker to measure the extent of injuries in living brains. With this technology, they hope to learn how well the brain can repair itself after experiencing concussions.

The team started its study in 2015 with nine retired NFL players who had histories of multiple concussions from several decades earlier. The researchers measured translocator protein 18 kDa—or TSPO, a biomarker of brain injury—in six regions of the brain, including the hippocampus, which plays an important role in memory. TSPO levels are normally low in healthy brain tissue but become elevated after trauma to the brain. By looking at areas of the brain with high levels of the biomarker, researchers could see where injuries occurred. Compared to a control group of elderly men matched by ethnicity, education level, and body mass index but with no concussions, they found high levels of TSPO in several regions of the retired athletes' brains. This suggests that repeated head trauma causes molecular changes to brain tissue that remain decades after the trauma. Compared to the control group, the retired athletes also scored lower on some tests of their memory. More recently, the researchers studied a dozen current or recently retired NFL players who reported having at least one concussion. Matched again with a control group, the athletes showed high levels of TSPO in eight of the 12 regions of their brains. Many of the young players scored well, however, on memory testing, leading Coughlin's team to suspect that age plays a role in memory loss along with concussions.

Coughlin's team hopes to continue studying the younger athletes to document changes in their brain tissue over time. They want to know whether the brain works to repair itself and if so, the role the athlete's age plays, since brain tissue is still developing into our early 20s. They want to know whether we can definitively link sports-related traumatic injuries to memory deficits and other psychiatric effects. Ultimately, they hope to offer preventive and therapeutic treatments, including therapies that could manipulate the immune system to speed repair of the brain cells. "The more we understand the way brain cells respond to inflammation and aging," Coughlin says, "the more we can come up with new ideas to help the brain repair itself."

Coughlin's research findings have left her a somewhat guarded football fan. As a Johns Hopkins undergrad, she enjoyed cheering on the football and lacrosse teams.

But she worries about the young adults she treats for mood disorders in her clinical practice. "Many of them play sports," she explains. "They've heard stories in the media about pro athletes having brain injuries, and these are NFL players who my patients look up to. They often ask me, 'Are the hits I'm taking in football going to impact me?'" Still closer to home, she thinks about her two sons, ages 1 and 3. "We have more questions than answers about the risks and long-term effects of brain injuries. I hope we have many more answers by the time my boys are asking me if they can play football."

Posted in Health, Science+Technology, Athletics

Tagged concussions, psychological and brain science, traumatic brain injury, sports injuries