Symphony Number One, an ensemble founded by Jordan Smith, a doctoral candidate in the Peabody Institute's orchestral conducting program, released its third album this week.

Titled More, it's SNO's first album to contain all original works commissioned by the group. More is available via the SNO website, iTunes, Amazon, and Spotify.

The album arrives as SNO prepares for a busy 2017. The ensemble has five performances scheduled this spring, and in October SNO was named one of the Baltimore Social Innovation Fellow by the Warnock Foundation, a local philanthropic organization. Smith plans to use the fellowship to underwrite a series of concerts in and around the Innovation Village in West Baltimore—a process that involves meeting with people and organizations in the community to figure out what such concert experiences should be.

"We're not just going to go into poor communities and tell them how it should be," Smith wrote in an email, adding that "Symphony Number One was founded at the exact same time as the unrest in 2015. From the first note we played, in a rehearsal that was actually cut short by the curfew, we've been aware of our place in the city of Baltimore. We're an orchestra, that most European of European institutions, in a city with deep turmoil and stress. Yet, being a diverse group that roughly tracks U.S. demographics and out-performs our industry, we see the value and the healing potential in the music of the orchestra that ways that cut across culture, income, age, and race. So even as we've been building, we've been devoted to figuring out how to use our work to serve folks all across the city, not just in a couple of isolated central neighborhoods.

"Instead, we're listening," Smith adds. "Fitting, I think, since that's what musicians do best."

More allows listeners to hear what SNO has performed recently. The album contains three pieces the ensemble debuted over the 2016 calendar year: Natalie Draper's Timelapse Variations, Jonathan Russell's Light Cathedral, and Andrew Posner's The Promised Burning.

Posner, a 2015 Peabody graduate, turned to the poetry of activist Wendell Berry for his piece, which is a dramatic, 21-minute-long mediation on human destruction of the environment.

The Hub caught up with Posner by email to talk about nature-inspired composers, conveying agitation in sound, and classical music's role in environmental activism.

Poetry that addresses, celebrates, and reflects upon the natural world abounds; sometimes less well-known are poetic texts wrestling with earth's man-made destruction. What was it about Berry's "The Sabbath Poems" that inspired you, and specifically this piece? Were there any lines or passages in particular that influenced the sounds, structure, or ideas in "The Promised Burning"?

What drew me to "The Sabbath Poems" was their radical honesty about humankind's relationship to the environment. There are a vast number of different moods, perspectives, and themes that develop over the course of the collection, and the majority of them do not address man-made destruction of the earth or explicit environmentalism at all. The collection as a whole presents an autobiographical summation, over more than 40 years, of the nature of relationship in all forms—with oneself, one's family, one's farm, neighbors, surrounding forests, and so on. Many of the poems are of that celebratory, reflective style that has always abounded in poetry; all the more poignant, then, are the poems that shatter any of our remaining delusions about the nature of the particular relationship between humankind and the environment.

These are the snippets of poetry I used to guide my concept for the piece. Musically, they line up with the five major changes of tone and rhythm that occur over the 21-minute span.

I. "I go in pilgrimage / Ruin is in place here" II. "To live as mourner of a human friend" III. "We have ourselves to fear / We burn the world to live" IV. "To mourn an ancient woodland / Grief as landmark" V. "By what blessedness do I weep?"

I get the impression that there's a modest tradition of American composers who draw some inspiration for their work from the natural world, from Charles Ives and Virgil Thompson and on through Aaron Copland, John Cage, and John Luther Adams. Is there a similar lineage at all dealing with environmental crisis? If not, how did you think about dealing with such a pressing issue in a symphonic language that, when it considers the environment, leans toward the celebratory instead of the lament?

If there is a lineage among modern classical composers that specifically deals with environmental crisis, I'm not aware of it. My conceptual inspiration actually tended to come more from folk music and heroes—including Pete Seeger, Willie Nelson, and Gordon Lightfoot—than from anyone who's ever set foot inside a music conservatory. I clearly haven't adopted any of those artist's musical habits, but the directness with which they convey their environmental messages is something I perceive as rare these days. (There are plenty of analogues to that directness with regard to other topics in modern opera).

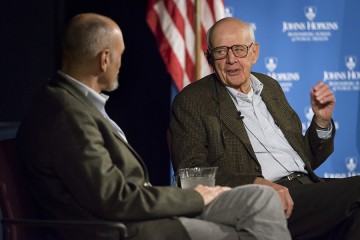

Image caption: Andrew Posner

I found it challenging to devise a musical language that suited both my aesthetic interest at the time and the concepts of the piece. Imitating birdsong only goes so far. What I eventually realized, about halfway through the composition process, was that the piece was not only about environmental destruction, it was also, perhaps mostly, about grief, as is evident from the poetry above. It occurred to me the musical language I employed would need to be flexible enough to address both of these topics, separately and simultaneously.

I think there's also a great deal of agitation, if not insistent anger, in the piece—I'm thinking about the clash of strings, percussion, and what sounds like low-end brass instruments about a minute and 45 seconds in, a tension that returns a few times over the course of the work. Could you tell me a bit about the emotional terrain you're covering in the piece? I ask because even when symphonic music gets angry for lack of a better term—such as in the second movement of Shostakovich's Symphony No. 10, or even the "Dies Irae" from Verdi's Requiem—there's a lyricism coursing through them, and you seem to be aiming for something that doesn't so easily conform to, well, being sweepingly pleasing.

The aesthetics of my piece were informed by two aspects of environmental destruction—scope and finality. It is my perception that our species has never faced any challenges as monumental, consequential, and irreversible as climate change and environmental degradation, and I suspect most climate scientists would agree. I don't think this is evident to most Western consumers, as we are not the primary group exploited in the name of globalism.

The emotional terrain I cover in the piece is a prediction of the grief our society will feel once these issues do become widely evident, and I felt that my typically lyrical musical language alone would be unable to create that emotion. The Shostakovich movement that you mentioned approaches my language much closer than does Verdi's "Dies Irae," but even Stalin and Hellfire pale in comparison to the global environmental catastrophes we are only beginning to experience. My task was to create a wholly original musical paradigm that could adequately address these issues and bind together a 21-minute form.

I consider there to be two overarching moods that bind the piece together: agitation, characterized by quick, reactive passages of repeated gestures; and grief, characterized by states of suspended motion and lyricism. These are clearly separated and distinguishable from one another until the passage around 9:15, after which point they begin to interact and wrestle for control. The agitation seems to emerge victorious at the piece's climax around 15:00, but the bowl gong that follows signals a new, deeper kind of grief than before—grief for a place, or in Berry's words, "Grief as landmark".

This more profound state of absence and suspension continues through the end of the piece and represents the most important part of the piece's message: that grieving a place is not like grieving a person. This kind of grief does not heal with time. It is an emotion most of us have never truly experienced and from which no one in future generations will be spared. Indigenous peoples all across the globe know this very well. In my view, no somber melody nor clever key changes are adequate to express this, and it is beyond the semiotic capabilities of lyricism.

Could you talk a bit about the percussion in this piece, including the piano? I ask because it sounds like you're interested in their force, the physical action of hitting seems to suggest civilization's encroachment and violence to the natural world. As in, I think the percussion is doing more than marking time here, and I just wanted to hear a bit about how you were thinking of using them.

You've read my mind. I would characterize this piece's treatment of rhythm as ritualistic and brutal. On a practical musical level, the inexorable fast notes in the agitated half of the piece highlight the periods of suspension and stillness in the other half, and vice-versa. The earthy tone of the drums seemed to fit the kind of brutalism I strove to create in this piece. In a way, I view every instrument in the piece as percussive—the forcefulness of the strings and brass during the agitated sections creates an air of violence, as does the striking of the bowl gong. You are completely correct to link this to our civilization's war on the natural world.

Can contemporary classical music play a role in environmental activism? Or is a better question why aren't today's symphonies including more contemporary composers who address contemporary issues in their repertoires?

Contemporary classical music can absolutely participate in environmental activism, and in discussing contemporary issues in general. It's just tricky to accomplish convincingly within a symphonic medium without vocalists or multimedia or anything like that to help. This is one of the reasons why I'm so excited about new opera—I think it's the most promising medium for musical activism. The Promised Burning was my first attempt, and I'm sure I'll make many others.

I don't subscribe to the doom-and-gloom narrative about the symphony orchestra's role in 21st-century culture, but I wish that orchestra conductors and managers would do more to seek out younger composers, from all varieties of backgrounds, who write about contemporary issues. I believe music to be unique in its capacity for clear communication about the issues that face our world, but that capacity will remain unrealized for as long as orchestras continue to program concerts that almost exclusively represent the ideas of the long-dead. What is necessary is only a level of sincere care for humanity and the courage to reach out into the unknown. There are thousands of young activist composers in the United States alone, and we will continue to voice our opinions and concerns through our art. I can only hope that orchestra conductors and managers will listen.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged classical music