"Can you move to Washington tomorrow?"

This abrupt inquiry was posed one day in 1965 to James McPartland, then a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University. It came from his mentor, sociologist James Coleman.

And McPartland did head briskly to the capital, one of six scholars to join Coleman on a massive new research endeavor. Tasked by Congress, the team was to undertake the country's first meaningful investigation of civil rights issues in education. They had a year and a half.

"All of us knew the potential importance of this project from the beginning," recalls McPartland, now retired after decades as a JHU sociology professor. "There was a great spirit and intensity to it."

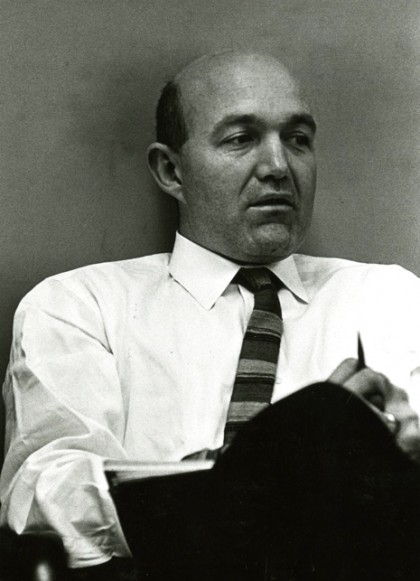

Image caption: James Coleman

Image credit: Sheridan Libraries Special Collections

A half century after the landmark Equality of Educational Opportunity Report (EEOR) came out in July 1966, it remains known as one of the most influential education studies in American history. Defying conventional wisdom, its findings revealed that a student's background and family mattered more for their success than the quality of their school.

"It is still inspiring current reforms," says McPartland, who will be the keynote speaker for next week's Coleman Report at 50 conference at Johns Hopkins.

The event, slated for Oct. 5-6 and organized and hosted by JHU's School of Education, will attract leading educational researchers and policymakers from across the country to reflect on the report's impact and modern implications. U.S. Secretary of Education John King is slated to attend.

"A 50th anniversary is a big deal for a document like this that still has a living, breathing legacy," says Karl Alexander, a retired JHU sociologist who helped organize the conference. He's co-chairing the event along with Stephen Morgan, a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Education at Hopkins.

Civil rights and schools

As a mandate of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the EEOR came together in the midst of a charged political climate, as the country struggled to desegregate its schools. It was thought the research would offer hard scientific proof that school segregation remained widespread, and that black students suffered from inferior resources and conditions in their schools. The Coleman Report did support those points, but its findings were more complex than anyone expected.

The study concluded that the achievement gap between black and white students did not seem to stem from race-based disparities in school resources. Family background, it turned out, was more critical. Also important were the socioeconomic composition of a school and a student's sense of control of their environment.

The researchers had examined data from more than 4,000 U.S. schools.

"Schools bring little influence to bear on a child's achievement that is independent of his background and general social context;" the report read. "And this very lack of an independent effect means that the inequalities imposed on children by their home, neighborhood, and peer environment are carried along to become the inequalities with which they confront adult life at the end of school."

The findings were a disappointment to some, including President Lyndon Johnson, who had hoped to build funding support for his War on Poverty. He expected the EEOR to prove more firmly that inadequate resources, especially in the South, were setting back poor and minority students.

The government released the report quietly on a slow news day before July 4, but over time it gained attention. A group of Harvard scholars, convened to analyze the report, determined that it had "turned a major area of social policy upside down."

The media and policymakers dwelled on one prediction from the study—that black students would achieve higher test scores in integrated schools with sizable white enrollment.

But Coleman himself, in a follow-up study in 1975, declared the practice of busing black students to white schools a failure, largely because it provoked "white flight" and therefore counteracted the intent of racial balance. These findings were controversial, diminishing political support for busing and turning many desegregation advocates against Coleman.

50 years of impact

Five decades after the original report, social scientists have found more sophisticated ways to chart disparities in U.S. education, but those disparities remain nearly as glaring.

At the upcoming Coleman conference at JHU, David Steiner, director of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy and former New York state commissioner of education, will guide presentations on policies since Coleman that have aimed to narrow the achievement gap.

Sociologists Alexander and Morgan have co-authored an article on the report's legacy and its implications in present-day Baltimore. Their piece will introduce a gathering of new reflections on the Coleman Report, available Oct. 5 through a free online edition of The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences.

Alexander spent time with Coleman on the JHU faculty in the early 1970s, before the latter rejoined the University of Chicago.

"I was fresh out of grad school, and to come to his department was very heady business," Alexander says.

During his time at Hopkins, Coleman—who died in 1995—founded the Department of Sociology and, following the EEOR, the now world-recognized Center for Social Organization of Schools.

McPartland, who later directed that center, says it used the Coleman Report's findings as "inspiration for practical reforms" that are still going strong today. Those include the Talent Development High School model, which breaks up large student bodies into more personalized "academies."

Alexander, meanwhile, says he was "steeped in Coleman for all my professional life." For more than 20 years, he taught a Johns Hopkins course on the sociologist's major studies. They continue to inform his current work, which includes organizing the Thurgood Marshall Alliance to encourage greater economic and racial diversity in Baltimore schools.

"Part of the inspiration for this project is what I know to be the evidence from the Coleman Report," Alexander says. "One of the best things you can do for poor kids is help them escape the drag of concentrated poverty in their neighborhood and schools."

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged education, karl alexander, equality, coleman report, james mcpartland