D. Watkins' first book—The Beast Side, which came out Tuesday—is a gripping immersion in the realities promised by its subtitle, Living and Dying While Black in America. It includes a few of his essays mentioned in last fall's Johns Hopkins Magazine profile, his incendiary wit and compact sentences cinematically capturing the lives of overlooked people in Baltimore. It also includes a number of new essays that continue Watkins' verbal immediacy but display an even more palpable vulnerability in piercing stories about the ways in which generations of poverty, disenfranchisement, and capitalism's exercise of power can erode both body and soul.

But there can be a way out, and for Watkins that path begins with reading. In Beast Side's foreword, Watkins notes that he's focusing on literacy broadly defined.

"Telling our stories and educating people are the best things we can do, if we hope to pull ourselves out of this bloody mess," writes Watkins, who earned a master's from the Johns Hopkins School of Education in 2011. "My goal is to write stories that get nontraditional readers excited about reading—as reading saved me."

That's not mere advertising. In addition to his contributions to Salon.com and a recently debuted column for The Baltimore Sun, over the summer Watkins worked with the Inner Harbor Project, which partners with teenagers in social change endeavors, and he's currently working on a mentoring project with Baltimore high school students funded by the city's One Baltimore campaign.

Also see: Super Ambitious: D. Watkins talks books, Baltimore, and his new collection of essays, 'The Beast Side' (City Paper)

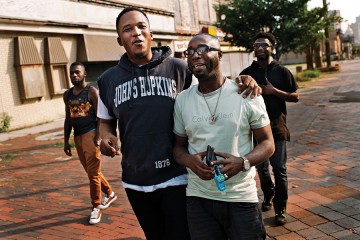

The Hub caught up with Watkins—who launches his book tour today at the Union Baptist Church in Baltimore—to talk about literacy, political consciousness, and trying to find something positive in the well-publicized string of African-Americans being oppressed and killed by law enforcement.

In your New York Times op-ed about Freddie Gray, you write that some people might ask why Baltimore, but the real question is, Why did it take so long? And you allude to Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, and national events and movements that followed those deaths. And I'm old enough to remember when those two Violent Crimes Task Force plainclothes cops killed Anthony Darryl Redd in 1994 here in Baltimore, and there were protests at City Hall then about police brutality. And there's really not, in content or sometimes wording, that much difference between what's being talked about in #BlackLivesMatter's social media activism and the Black Panthers' Ten-Point Program—fair housing, the way capitalism destroys disenfranchised communities, decent education, access to health care, and, one of the points reads, "We want an immediate end to police brutality and murder of black people." I bring that up not as a knock against what's going on now, but to me it's a very clear indication that very little has changed in roughly 50 years. So when you ask Why did it take so long? in your essay, I wanted to know if you could talk a bit about what brings it to a head. I mean, you write that growing up in Baltimore you see incidents like how Freddie Gray was handled by cops all the time. So why didn't it happen earlier? Why now?

I was working on an article that I've never put out called "No Cell Phone Camera, No Peace," because I feel like a lot of these things would not have been taken to trial if they weren't caught on camera. The reason I trashed the piece was because Eric Garner's death was caught on camera and it still didn't mean anything. A chokehold that was outlawed was clearly used on camera, and it still wasn't enough to get an indictment.

So a few things—one, I think the most positive thing that I can take away from all of these negative police interactions and police murders is I think it brings more awareness to the situation. Before, there were a certain [number] of people outside these communities saying, You guys complain, you guys make this stuff up. Just pull yourself up by your bootstraps and live the American dream. Now, they have to sit back and watch somebody get murdered on the 24-hour news cycle over and over and over until it beats them in their heads. And it's sick, and it's sad, and it's disgusting, and they have to digest it just like the people who have to live in those areas.

And this is not just murders—when you see some of those Facebook videos that go viral of the kids who fight, you see how they live. You can see where they're being educated. You see the possessions that they have. So why did it take so long? Technology was a missing link. The world is very sectioned off, even in a city like Baltimore. It's a city of neighborhoods, neighborhoods that emerged out of necessity. You can live three blocks away from a person and never see them, interact with them, or even experience the same reality. A well-off person can be doing amazing things a few blocks away from somebody just trying to figure out how to get from Tuesday to Thursday.

And I look at [police brutality] as bullying. How long does it take for you to bully a person before they actually explode? It took a long time here, but it finally happened. I don't know if we'll see something as wild as the uprising again during our lifetimes, but I still think that energy is still there. So technology was a key in that, and why did it take so long? I don't know, but the end result was social relations enhanced. Now, different people who wouldn't even be open to some of the things I write about are reaching out to me. I get so many emails that start out, "I'm an 80-year-old white Jewish guy ..." or a "I'm a 65-year-old white woman ... ," and these things going on are allowing people to connect. We all need each other in these wars.

In your introduction to The Beast Side you write about how you're tired of the same-old discussions about injustice in America. And that's why, for you, you're shifting toward talking about literacy, about how reading comprehension relates to issues such as poverty and injustice through communication—with other people and, I think it's implied, with yourself, in how knowledge shapes a sense of self. Tell me a little bit more about that—how communication feeds having a better understanding of a situation.

I had a professor at the University of Baltimore and we were covering the Reconstruction era and conversations about slavery came up. And through my readings, I came across something that talked about the basic rules for slaves on a plantation. And one of them was that it was illegal for slaves to read. And that made so much sense. I didn't read for most of my life. I was a slave for most of my life because I didn't know—no matter how much money I made, no matter what I could buy, where I could go, who I could beat up, who I could put pressure on, I was lost because all my ideas were just somebody else's ideas. I just borrowed them—and they probably borrowed them, too, because they didn't read. And they got transferred down to them from another person who borrowed them. So we're not even working with our own set of ideas.

So reading opened my mind up to all different types of things. Like, this is one of the things that people never really pay attention to or they never say this: When you think of African-Americans you think left—you think Democrats, left leaning, liberal ideology. Black people are very conservative, especially when you talk to black people who go to church. They're conservative and the whole idea of anything nontraditional is, like, What? Through reading you become more of an accepting person. You begin to understand that you don't understand, and you'll have a whole life of not understanding, but there's great value in taking that journey because you gain so much.

And reading has done that for me. So I feel like if I can help transfer that magic to somebody else, then I'm doing my part. And that's my part, and I know that's just a small part. I'm not the kind of person who is going to go lay in traffic and go to prison for laying in traffic. I don't even think laying in traffic is a good idea. I think laying in traffic only hurts poor people. I mean, I'm not anywhere close to being rich, but as an adjunct college professor, if I'm driving to work and there's people laying in the street, I can just pull out my phone and go to Blackboard and say, "People are laying in the street, I can't get to class. Read chapters 1-5, go to the discussion forum and leave a reflection, you're responsible for interacting with four different reflections, and then we'll have a bigger group discussion on Tuesday." And I'm going to go home. But if I work for Wal-Mart, and I'm driving down the street and people are laying in the street, I'm calling my job saying, "Look, I can't make it in—there's people laying in the street." My boss might be saying, "That's going on your record, and when you're up for your two-cent raise, I'm going to guarantee you don't get it."

So who are you hurting? You're not hurting the oppressor. You're not hurting the people who keep these systems in place. You're only hurting people that's living just like you. And the ability to think these things out comes from reading and thinking things out and developing a brain that's willing to be accepting but not accept whatever is thrown in front of you.

You don't come out and say so explicitly in The Beast Side, but for me it was humming in the background when reading through it. You talk about the relationship between reading comprehension and the ability to think, but I also felt you were illustrating the relationship between literacy and political awareness, the ability to form your own political awareness. And I think that's something every person goes through, regardless of background—like, I'm not trying to pick on her, but Jana Hunter's op-ed at Pitchfork about segregation and inequality in Baltimore and how it is echoed in the local music scene. Part of me felt, that's great—this fairly well-known local artist is using that platform to talk about the very real things going on where she lives. Another part of me was like, the discussion she's entering is also the result of simply opening one's eyes and recognizing the situation for what it is, one that many local activists have talked about for a long time. So that political consciousness is something that we're not born with, it's a process that we go through. So could you tell me a little bit about what has shaped or informed your political consciousness, as a person and a writer.

When I was a kid, I used to be a really opinionated little asshole. I used to ask a billion questions to everybody all the time. I couldn't wrap my head around the idea that there was no answer—everything had to have an answer. How many pieces of lint could a shirt accumulate in a two-hour period? No, there has to be an answer to that. That can be a good thing because it means you're an inquisitive person, but it also can be very frustrating. So what shaped me was being exposed to a world outside my own world. I remember not really connecting with other people because they lived in certain neighborhoods. And it wasn't a gang thing, it was just, You live on that side of Baltimore? You're soft. You got grass and trees and family members that went to college. That's a soft person. But being exposed to things through literature and experiences opened my mind up and shaped me to have a different opinion.

But I can't front. When I first started following politics, it was straight Democrats, Democrat, Democrat. But now I don't know if I have any strong political affiliations at all.

I mean political not just in the American two-party context, but political in the awareness that if there's a growing service industry instead of manufacturing industry, recognizing that there's a reason for that and there is an intentionality behind a system that facilitated that development.

That part of my education came from being a history major. Some of my articles reach back to some of the research I did when I was a history major. I already knew we were fucked, but from that point on I realized why and how—from everything like how neighborhoods and voting districts are redrawn and what it takes to sustain American capitalism. I realized that what's going on now isn't a mistake. This is a system that works. It doesn't work for you, it doesn't work for me, but it's working for, I don't know ...

Procter & Gamble.

It's working great for them, and they love it. And then you have to realize your place in that system. So when you get this history education through reading, you have the potential to figure out ways for the system to work for you—do you want to be a person that benefits off that? Or do you want to be a person who tries to get in there and create opportunities for people so they can benefit from it, too? You have to pick a side. You can't do both.

I know people who make a lot of money off what I call the ignorance tax. Like guys who sell cars. They'll go to the yard and get a car for $450 and then they'll finance it to some single mom for $6,000. They're able to exploit the system in the same ways banks do. And the single mom might not know any better. She's just happy to be able to get in the car and drive to work and her kids aren't getting rained on at the bus stop. And her not knowing what's going on, and not having the money to be able to go purchase the car herself, she's now sucked into that exploitative system. And that's horrible.

I don't want to be on that side or with anybody associated with that. Though too many people are born in poverty in Baltimore, I still think there's a way to make the American dream work. The key is to redefine what the American dream is. You got to deliver those skills that can make that dream happen. That's reading, that's understanding how the system works. That's understanding how you make it through a fucked-up school, how you make it through a fucked-up neighborhood. It's difficult, but if we can get to a point where we're acknowledging all these issues that are stacked up against us, then more people can experience it. This is why I have to work really, really hard with the young people I work with. I have to believe that I can contribute something so we can push toward something better or I wouldn't be able to do anything.

I wanted to ask about that personal drive for you. You mention that shift toward literacy in the book—how did that contribute to the writing choices you made when putting together the book, the pieces that weren't already published someplace else? Did it frame what you wanted to discuss?

This whole book project wasn't even my idea. You never know who's watching. David Talbot, the founder of Salon, was watching and I didn't even know it. So when he came to me with this idea, I was surprised. I mean, you know where I was at at that time—You're going to give me a check for writing? I haven't got a good one of those in a minute. So I was down with the idea, I was down with working with him, and he believed in the project and worked really hard with me to develop it. I still consider myself a student, I'm still learning. So there was some pressure to write some of the new stuff, there was pressure to go back and edit some of the old stuff, and then there was pressure to get it done really quick.

So you never know who's watching. I'm totally happy with the idea of having a following of high school and middle school students who check for my essays, or who see me on the street, who say, "Yo—ain't you that writer? We read you in class." That's honorable to me, and for them to be excited about it? I mean, I think about when I was their age, and they're already reading and having these ideas, then I know that they have the potential to do way more stuff than I can even imagine. I didn't become a writer until I was almost 30 years old. So to know that they're on the same wave at 14? It makes me feel like something positive can happen.

D Watkins also appears Sept. 25 as part of Red Emma's Radical Bookfair Pavilion at the Baltimore Book Festival and Oct. 22 at the Enoch Pratt Central Library.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged books, baltimore, writing, d. watkins