Although critics knock United States-based companies like Apple, Google, and Starbucks for dodging taxes overseas, a new analysis shows that European companies in the U.S. are enjoying the same sort of tax breaks.

A paper co-authored by two Johns Hopkins University researchers and published today by the Progressive Policy Institute, concludes American companies are indeed getting tax breaks in Europe, but foreign companies in the U.S. are paying as much as 40 percent less federal income tax than their American counterparts.

"European politicians who complain about knowledge-based American companies not paying enough taxes in Europe have a point," the authors write. But, "they are also being hypocritical."

Paul Weinstein, director of the university's graduate program in public management, and Sarah O'Byrne, a program coordinator with the Center for Advanced Governmental Studies, wrote "The Blame Game: Multinational Taxation in an Era of Knowledge" along with Progressive Policy Institute economist Michael Mandel. With international organizations such as Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development working to reform corporate tax rules in developed countries, the writers say the problem isn't as clear-cut as it seems and the low taxes some American firms are paying in Europe appear to be in line with international standards.

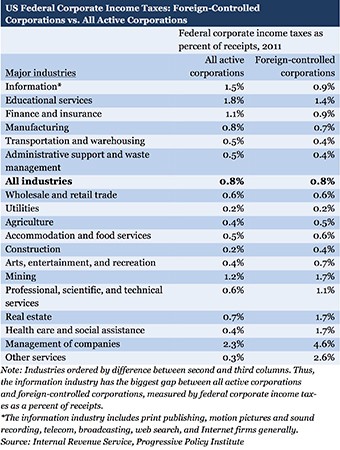

The researchers analyzed Internal Revenue Service data from 2011, the most recent year for which data was available, to compare taxes paid by foreign-owned companies in the U.S. with comparable domestic companies. For the entire information sector, domestic firms paid 1.5 percent of revenue in federal income taxes while foreign companies paid 0.9 percent—about 40 percent less.

Domestic companies also paid "significantly higher" federal income taxes than foreign ones in industries including information services, telecom, motion pictures, securities trading, electronic markets, publishing, electronic markets, and computer and electronics manufacturing, the team discovered.

"[W]e can infer that foreign companies [in knowledge industries] are able to arrange the location of their intangible capital in a way that reduces their taxes," they wrote.

In addition to federal tax breaks, state and local entities "typically dangle a variety of incentives," to foreign firms, the researchers found, including infrastructure improvements, free or below-market price land, and low-cost housing.

The size of these packages vary considerably by location and industry. According to the paper, in 2013, the group Good Jobs First found that 18 of the top 100 economic development packages in the U.S. went to foreign controlled firms.

These strategies adopted at the state and local level are directly comparable to the way that some of the most economically successful European countries, such as Ireland, have been able to build major tech employment bases with low tax rates, the researchers found.

"European criticisms of the taxes paid by American-based companies in knowledge-based industries are in part unfair, although there are clearly loopholes that need to be closed," the authors conclude. "As governments move towards implementing new structures for taxing knowledge-based multinationals, on a broader scale, they are going to have to decide whether they want more immediate tax revenue or more growth."

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged center for advanced governmental studies, tax policy, corporate taxes