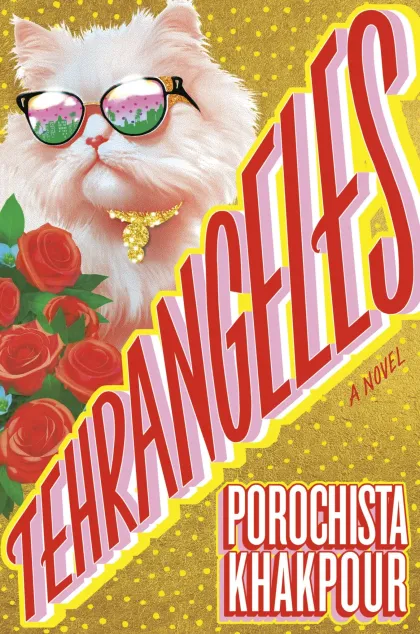

From the March sisters in Little Women to the Bennets in Pride and Prejudice to the ubiquitous Kardashians, there's something about a cluster of sisters that seems to snag our collective imagination. In Porochista Khakpour's new novel, Tehrangeles (June 2024, Penguin Random House), the sisters in question are the Milanis, four uber-wealthy young women, heiresses to a fast-food fortune: gorgeous, motherly Violet, a professional model; Roxanna-Vanna, aka Roxi, a brash, hard-partying influencer; thoughtful, K-Pop-obsessed Mina; and self-confident (and self-obsessed) Haylee. When we first meet the Milanis, they are about to star in a new reality television series that promises to catapult them to national fame. The show will also introduce the broader public to the glitzy world of Tehrangeles, the community made up of people who immigrated to Southern California from Tehran after the 1979 Iranian revolution and became the world's largest cohort of Iranians outside Iran. "If I had to describe our world, I'd say it's hell dressed like heaven, or the opposite," as Mina Milani says.

Over the course of four books of fiction and nonfiction, Khakpour, A&S '02 (MA), has become known for her thoughtful, wry probing of such subjects as anti-Muslim discrimination after 9/11, her battle with chronic Lyme disease, and life in New York City. Tehrangeles represents a departure of sorts: a satire of a world that's so over-the-top that it's dizzying to behold.

The novel, which started as a parody of what New York editors wanted from her, grew into something weirder and more empathetic than its original conception. As the Milani sisters (and their parents, Hoda and Al) negotiate the show's production amid a pandemic, Khakpour explores the perils of fame, the allure of conspiratorial thinking, and the persistence of grief—along with explorations of pet psychics, online fan fiction, and sketchy ayahuasca shamans. As Khakpour writes in her acknowledgments, "Thank you Tehrangelos who came into the Rodeo Drive boutique I was a shopgirl at and made it known they felt so sorry for me. As I smiled and nodded and showed you five-figure handbags, I thought to myself, One day, I will write about you. I never thought that through the exercise I would come to feel for you."

Johns Hopkins Magazine recently discussed the novel, with a detour to pop culture, with Khakpour.

Reality television is a guilty pleasure for a lot of people. What's your relationship with the genre?

I started watching reality television mostly because in 2011 and 2012 The New York Times Arts & Leisure section had me write about it—specifically shows with a Middle Eastern theme. I was also briefly on Shahs of Sunset— I was introduced as [real estate agent] Reza [Farahan]'s ghostwriter over Zoom on it. It was a short-lived stint. I've also had many friends who have been involved on the production end of it, so I've learned a lot.

If the Milani show were real, would it be a hit?

Probably! Not critically but commercially, sure.

You've said this book started as a joke—what do you mean by that?

It really was not a book I wanted to write. It was in response to publishers at the time, when I was shopping around my second novel, saying that they wished I was writing a book about Iranian women. So I gave [this book] an (almost) all-female cast of Iranian women.

When did it start to feel real to you?

I think when I began thinking about Little Women and then living through the pandemic, I got really hooked. It's been through so many drafts—it's come a long way since the draft of it that was sold in 2018 with Brown Album [Khakpour's essay collection chronicling immigrant and Iranian American life] to Knopf Doubleday. I had all the sisters, but the hundred or so pages I had then were mostly centered on Roxanna. I think the pandemic gave me the ultimate perfect setting for their ruin.

"Tehrangeles" is shorthand for a very particular, status-obsessed slice of the Iranian American community in Southern California. It's a world that's decadent, fun, and at times a bit appalling. It's also not the LA that

you grew up in. What drew you to want to write about it? What did your research consist of?

I never lived there, but I visited a lot and I even worked there. It's hard not to be drawn to it—it's hard to look away. I am interested in all things Iranian, so it felt natural. I also think I, more than many Iranian authors, love pop culture and satire, and so if someone had to do it, it had to be me, probably. I just could not believe we didn't have a Tehrangeles novel, you know? It seems necessary to tell that story. And I didn't need to do a ton of research on Tehrangeles since I always find myself there anyway. It was more the depiction of Gen Z girls that I wanted to get right.

The looming prospect of the show spurs the Milanis to interrogate their experiences as Iranian Americans. Many of the characters have mixed feelings about how the show will depict them as "the first Iranian reality TV family." What are the potentials and pitfalls of this kind

of spotlight? Is "representation" always a good thing?

I've often said that the endgame should actually be invisibility. For many years, I was most haunted by pigeonholing. But that was before I realized in the West, people still barely see us. So I think that we should still strive for representation—but I do think it's very Iranian to have mixed feelings about it. After all, we are a huge country very central to the Middle East. And we loom large in the American psyche, especially over the past few decades. People are obsessed with us, it seems, and not always in good ways.

The novel takes place in 2020. I think we're just starting to see the impact

of COVID-19 on literature. Was it challenging to write about the pandemic?

Not really. I wrote about 9/11 pretty immediately after, too. I think a lot of writers hold back from writing about these major global events as they worry audiences are sick of it or somehow don't want to hear it, but I never focus on commercial concerns. I think it's natural to write about things close to you. I lived in Queens during the pandemic, and it was very hard-hit. And I was fascinated watching the influencers unravel around that time, with their superspreader parties and their subsequent cancellations and all that. It felt not only natural, but it gave me the perfect parameters of setting that I needed to complete the book.

Mina, the third-youngest (and most relatable) sister in Tehrangeles has health issues for which, as you write, "there was no one diagnosis." Chronic illness is a subject you've explored in your nonfiction work. Did you always know this was going to be part of Mina's arc?

Also see

Yes, Mina is the character I relate to most, so I wanted her to have a lot of my issues and interests. I had a particular investment in her survival. I also think it's important to have chronically ill and disabled characters in literature, so it made a lot of sense to me to give her that arc.

Without spoiling too much, I was surprised (and, honestly, delighted) that Roxi, the most unapologetically over-the-top sister, got the last word. Did your feelings for her, or for the other characters, change over the course of the decade-plus you spent writing the book?

Yes. The big challenge for me in writing this book was getting myself to actually feel for Roxi. I really did not like her. I found her very hard to write and just so grating. She does so much that I disagree with. She's a true nightmare, and she wouldn't disagree with that. But I knew that if I could develop some genuine affection for her, the book would be on the right track. I tried so hard to root for her. The final chapter was my best attempt, in a way. She's actually a pretty classic tragic heroine. I have a sequel in mind, and her story in that one is quite different, so I hope this book does well enough to allow me to release that second book into the world.

Posted in Arts+Culture