On the evening of October 22, 1962, Americans who gathered in front of televisions to watch Monday's entertainments—the game show shenanigans of To Tell the Truth or perhaps the cowboy drama Cheyenne—were instead greeted with a stern-faced President John F. Kennedy broadcasting from the Oval Office. The Soviet Union, he solemnly declared, was engaged in a "clandestine, reckless, and provocative threat to world peace."

They were sending nuclear missiles to Cuba.

The United States would not tolerate such "deliberate deception and offensive threats," Kennedy continued, announcing that a naval blockade of the island was underway. Thus began a tense two-week stretch when the Cold War nearly became hot, and the era's duck-and-cover schoolroom bomb drills seemed poised for the ultimate test. We later called it the Cuban missile crisis. There was no direct hotline between Moscow and Washington—the so-called Red Phone wasn't installed until 1963—and it could take hours for written communications to wind their way through diplomatic channels. As ships clashed on the high seas, Kennedy hunkered down with military commanders and advisers dealing with a back-and-forth salvo of letters. Deep in the bowels of the Kremlin, his Soviet counterpart, squat, bald-pated Premier Nikita Khrushchev, kept his stenographers busy with a stream-of-consciousness torrent of words. Some of them concerned potatoes. The Cuban-bound Soviet ships, Khrushchev declared, contained only "ordinary potatoes" and that Kennedy will "feel ashamed" to board them and find spuds, not warheads. "If I were in your shoes, I'd be shocked!" he added.

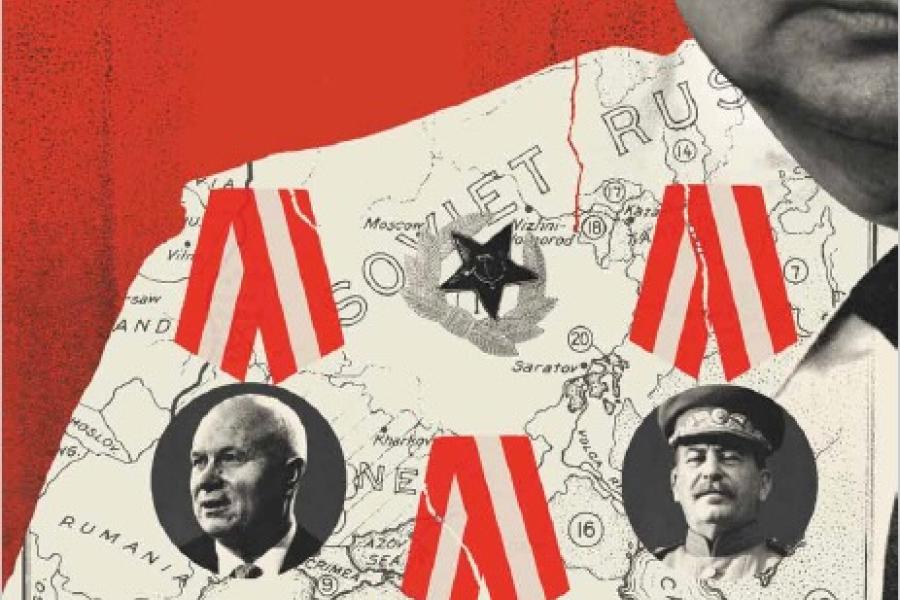

None of this potato talk made it into the official communications that ultimately wound down tensions. A Soviet leader saying such nonsense while U.S. forces were in Defcon 2, the penultimate alert level before Armageddon, reads like surreal comedy. But it's also an intimate glimpse inside the Kremlin that humanizes Soviet leadership, which can too easily dissolve into Boris Badenov stereotypes. And that's why it's important to Cold War historian Sergey Radchenko, professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies in Europe. Khrushchev's potato rant can be found in Radchenko's decade-in-the-writing To Run the World: The Kremlin's Cold War Bid for Global Power hitting shelves in May. The book asks us to rethink much of what transpired—and why—between the fall of Berlin in 1945 and the fall of the Berlin Wall more than 40 years later.

"I think this rambling by Khrushchev, the strange stuff about potatoes, reflects that he's confused, angered, and embarrassed that his ploy has been uncovered by Kennedy," Radchenko says over Zoom from his home in Cardiff, Wales. "He shows the range of completely human emotions, which I think is actually a good thing when it comes down to the peaceful resolution of the Cuban missile crisis. Because if Khrushchev was a calculating unemotional machine, we may have well ended up in nuclear exchange."

Radchenko speaks with a subtle Russian accent, a byproduct of his hardscrabble childhood in Soviet Siberia (more on this later), and is an affable academic—as comfortable talking about his daughter's harp recitals as he is about Joseph Stalin's bloody machinations. While academic postings had him living in China for several years, he wrote two well-received books about Sino-Soviet relations based on his unprecedented (and short-lived) access to Chinese state archives.

About a dozen years ago, Russia began opening its archives and declassifying reams of Cold War documents, including heretofore unseen notes, memorandums, telegrams, and back-channel communications to and from Soviet leaders. If this move doesn't seem on-brand for Vladimir Putin, Radchenko points out that the Russian president considers himself an amateur historian and probably hoped that details within this blizzard of paper could bolster his own skewed view of the Russian experience. The materials—such as Stalin's handwritten notes and thickets of Khrushchev's dictations—provide a peek behind the Iron Curtain.

"You become something like a psychiatrist listening to these people—their frustrations, desires, and hopes from day to day," Radchenko says.

Along with fresh source material, Radchenko brings a fresh perspective to the project. The first histories of the Cold War, he says, were written in the 1990s by Western academics. Their tone was triumphant. Or, as onetime SAIS Professor Francis Fukuyama put it, the Cold War's pro-West conclusion represented the "end of history."

"I come from a generation of historians for whom the euphoria of the end of the Cold War has been replaced with a growing sense of disappointment that it did not actually usher in a brave new world," he says. "I also take an unusual approach of linking the Cold War to the present. It connects straight up to Putin."

When did the Cold War start? The book suggests Sept. 11, 1945. That's when the first post-war Conference of Foreign Ministers convened in London, and Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov said nyet to signing every proposed peace treaty necessary to usher in a post-war Europe. The Soviet Union had always been a curious World War II ally in the fight against totalitarianism, but as the adage goes: The enemy of my enemy is my friend. Erstwhile ally "Uncle Joe" Stalin was morphing into an adversary. Secret telegrams released from the archives show him calling the shots from Moscow, micromanaging Molotov the whole time. "In Stalin's eyes, giving even a little bit of ground would lead the Americans into deciding that pressure can force him to make concessions," Radchenko says.

Clocking in at almost 800 pages, To Run the World hits all the Cold War milestones: Sputnik, the Berlin blockade, the U-2 spy plane debacle. It also offers lesser-known tales, such as Fidel Castro's 1960 visit to the U.N. when he got into a fight over costs at his posh midtown New York hotel and decamped to a Black-owned hotel in Harlem. (Communist leaders made much hay out of highlighting America's racial disparities.) And then there's the 1958 meeting between Khrushchev and Chinese leader Mao Zedong that took place in the latter's swimming pool, fully detailed now for the first time. "You have these two wannabe Communists sitting in the swimming pool talking about how they will blow up the United Nations and construct a new United Nations out on an island in the ocean, and how in the future, Communist toilets will be made of gold," Radchenko says. "You read it and think they're crazy. But it does give you a very intimate portrait of their ambitions. And their delusions."

What you don't see a lot of in these archived materials, and hence the book, is ideology. Espousing the glories of Marxist-Leninism and boasting how the Soviet Union would crush the greedy imperialists and create a global workers' paradise were more the stuff of canned speeches. "Soviet leaders themselves did not necessarily see ideology as defining their foreign policy behavior," Radchenko says. All their talk about being the people's champion clashed with their on-the-ground actions: invading Hungary in 1956, crushing the Prague Spring in 1968, marching into Afghanistan in 1979.

"If everybody would embrace Communism and it was such a great idea, then why do you have to send tanks into Hungary to impose it on people?" Radchenko asks.

If it wasn't dogma that motivated the Soviet leadership, what did? They sought security for the regime and reveled in notions of prestige and greatness. Ultimately, Radchenko settles on "legitimacy" as a key driving force. Not a sense of internal legitimacy as proffered up by just-for-show elections (which Putin is still holding), but legitimacy on the world stage. And that legitimacy had to come mostly from the United States treating the Soviet Union as a superpower—an equal partner on the world stage with the right to throw its weight around.

"From Stalin onward, they really prioritized recognition of their gains and their position by external powers because that recognition endowed their gains and their position with legitimacy," Radchenko says.

China's emergence on the world's stage by the late 1950s complicates things. When Mao proclaimed the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, he recognized they were the new Communists on the block. Stalin was the big brother. "According to Mao, Stalin was this wise revolutionary and was one of the prophets of socialism," Radchenko says. Stalin's successor, Khrushchev, was another matter. With scant history as a revolutionary, "he was a clown as far as Mao was concerned," Radchenko says.

With China's rise, the Soviets faced a dichotomy and tried to ride an improbable see-saw. "On the one hand, they desired to be recognized as a great power by the United States," Radchenko says. "On the other hand, they wanted to be recognized as the leader of the so-called revolutionary world, mainly by the Chinese. Whatever policy they pursue, whether it's détente with the West, missiles in Cuba, or the Berlin Wall, they'll look over their shoulder and see what the Chinese think about it."

Between his fluency in the requisite languages (English and Russian, of course, but also Mandarin and Mongolian) and his fortuitous access to state archives, Radchenko is perfectly positioned to be a Cold War authority. But his scholarship is also grounded in his lived experience as a Soviet citizen.

The family lived on Sakhalin Island, a subarctic island a little larger than Maryland located off Russia's far east coast. To paraphrase the writer Anton Chekhov, who endured a visit in the 1890s for a travelogue, Sakhalin doesn't have a climate, only bad weather. Think of it as Siberia's Siberia. Kremlin leaders in Moscow—multiple time zones to the west—made it a militarized border area. Travel to and from was highly restricted. Sakhalin's Cold War claim to infamy came in 1983 when it was where a Soviet fighter plane shot down a South Korean airliner that had errantly strayed into Russian airspace. All 269 passengers and crew were killed.

"We lived on the fifth floor of this dilapidated apartment that was literally falling apart," Radchenko says. Hot water was nonexistent and electrical service fickle. Heck, even cold water was a sometime thing, and the family planned accordingly when it flowed. "We would fill the bathtub with water so that you could use it later to wash stuff," Radchenko recalls.

He is quick to point out his proletarian bona fides: His father spent long stretches at sea with the Soviet fishing fleet, and his mother worked in a cardboard box factory. ("There are no academics or professors in my background," he says.) The factory connection proved pivotal in nudging him toward academia because through it he secured a ready supply of one commodity: books. "As a kid I was just reading, reading, reading," Radchenko says. The family always brought home state newspapers such as Pravda—but mainly because toilet paper was just another thing the shops lacked.

You could say his career as Cold War scribe began at age 7 when he wrote a letter to President Gorbachev. "I was complaining about some aspect of life in the Soviet Union," Radchenko says, the specifics having been lost. (In any event, his mother thought it wise not to put it in the post.) He was 11 in 1991 when the Russian tricolor replaced the hammer and sickle flying over the Kremlin. Life on the island got worse: "It rapidly deteriorated into a real Wild East with high crime," Radchenko says. But he might still be on Sakhalin eking out a meager existence if not for an improbable, globetrotting chain of events that kicked off in 1995 when a U.S. student exchange program brought him to, where else, Texas.

Before long, this denizen from the land of atheistic Communism who'd worn the red scarf of the Soviet Young Pioneers (think, Communist Boy Scouts) was enrolled at East Texas Baptist University. Learning that the school had a Hong Kong affiliate, he soon elected to head east and learn Mandarin. The London School of Economics and Political Science came next, his studies challenged by poverty (he often slept in the college computer room) until the Open Society Institute offered him a fellowship to teach in, where else, Mongolia, where he lived for a few years while finishing his PhD.

Given the cataclysmic outcome of a full-on nuclear war, succinctly encapsulated in the acronym MAD (mutually assured destruction), Radchenko's book shows how the fate of the planet and the billions living upon it came down to personal relations formed among a handful of leaders with access to the launch codes. Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev led the USSR between 1953 and 1982, a stretch of nearly three decades, during which the U.S. had eight different presidents—and so eight opportunities to make human connections that might keep fingers off buttons. Relations wax and wane, but the presidents the Soviet leaders ultimately never warmed to include Truman, Johnson, and Ford, as well as Carter, whose human rights agenda annoyed the Soviets, Radchenko says. "It was counterproductive because it didn't help the human rights situation in the Soviet Union and it showed that the Americans were arrogant and trying to teach the Soviets how to live."

In contrast, Brezhnev and Nixon enjoyed a frenemy bromance before the world's cameras. The Soviet president went out on a limb inviting Nixon to Moscow in 1972 while bombs were raining down on Vietnam. Nixon returned the favor the following year, and Brezhnev visited Washington, Camp David, and California. During the trip, Nixon presented Brezhnev with the keys to a new Lincoln Town Car. But beyond the public backslapping, they got some things done, such as the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty. "Brezhnev treasured his partnership with Nixon much more than any ideology prescriptions," Radchenko says. "That's because he regarded Nixon as a peer whose recognition he craved because it added to Brezhnev's own sense of legitimacy and power."

It was an improbable pairing given Nixon's history of red-baiting, but his high-profile bread breaking with a sworn enemy served as a distraction from his own issues: the quagmire of Vietnam and his eventual descent into the swamp of Watergate. Indeed, after the scandal began sinking his presidency, documents from the archives show Brezhnev trying to help. "He asked the head of the KGB if we could help Nixon somehow," Radchenko says. "Did they have something against Nixon's enemies?" Brezhnev's health deteriorated after 1974, and senility set in. His image in decline—glassy eyes beneath exuberant brows reading Soviet boilerplate in a monotone—can stand in for Moscow's sclerotic leadership. A pair of short-lived, wizened men led the USSR after Brezhnev's death in 1982 before 54-year-old Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in 1985.

And Gorby inherited a mess, the book shows. Soviet shops continued to offer little for buyers, and the developing world had fewer and fewer buyers for the promise of Communism. Gorbachev rightly enjoys a reputation as a domestic reformer, but Radchenko also sees a lot of continuity in his priorities—essentially playing Brezhnev's game of global grandstanding, such as with his call to eliminate all nuclear weapons. "He wasn't serious about it," Radchenko concludes. "He was a politician, and he would know how difficult that would be." This last Soviet leader essentially launched an eleventh hour peace offensive to rebrand the USSR on the international stage—a sort of geopolitical New Coke moment. The benevolent bear. Radchenko got to meet and interview Gorbachev and the pair shared a chuckle over the letter the young Sakhalin islander tried to send to him. The Soviet Union was over by then.

Some historians and scholars, including Radchenko's SAIS colleague Professor Mary Sarotte, argue that the United States and the West could have initially done more to support Russia and its fledgling democracy. Radchenko has some sympathy for these arguments, but in the end he's blunt on who's to blame for where things ended up. "The Russians should just recognize their own failures and stop blaming them on others," he says. In the wake of Communism's collapse, Russia became a "a corrupt wreck of a country" that still found time for "imperialistic tendencies," such as the 1994 invasion of Chechnya. "The Russians should learn to accept that they have certain imperialistic proclivities that scare their neighbors and create problems for their foreign policy."

And here we are. History hasn't ended; it's being written in Ukraine's smoking cities and the grim trench warfare scarring its wheat fields. Putin calls the collapse of the Soviet Union a "geopolitical catastrophe." The ex-KGB man is certainly nostalgic for the days when the Soviet Bear strode mightily across the globe. He doesn't even have to pay lip service to any complex political ideology. There's no Das Kapital in the background, just the strongman's playbook: rabid nationalism seasoned with appeals to "traditional values." (One throughline from the Soviet Union to Putin's Russia is a national dependence on revenue from oil and gas exports.)

Also see

And as for the legitimacy his Soviet forebearers sought in world affairs? Putin's turned that on its head. "He has set himself up as almost a leader of a kind of anti-American coalition of various states in the global south and so that is a legitimating aspect for him," Radchenko says. "He's chosen this confrontational policy with the United States saying, OK, if you don't recognize us as a partner, then we are happy to be recognized as an adversary."

For the book's concluding chapter, Radchenko turns to not the archives but the bookshelf and the sublimity of Russian literature: Dostoyevsky's Crime and Punishment, with its impoverished student antihero Raskolnikov who murders an elderly pawn broker with an ax.

Am I a trembling creature, or do I have the right? runs one of Raskolnikov's internal monologues as he flirts with the notion that he possesses an inherent exceptionalism freeing him from conventional morality. Putin's 21st-century rewrite swaps the ax for cruise missiles.

"The difference between Raskolnikov and Putin is that ultimately Raskolnikov cannot live with the guilt of having committed the crime, and he drops on his knees and kisses the ground and sort of asks the world to forgive him," Radchenko says. "And Putin is not ever going to do that," he adds, "because he's got nuclear weapons."

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged soviet union, russia, cold war