As a kid, Levert Brookshire III remembers running away from his father's house. After his parents separated when he was 7, he split his time between them. But around 11 years old, he began sneaking off to see his mother, with whom he had a deep connection, to escape his father's rigidity. Now in his 50s, Brookshire still describes himself as a mama's boy.

"It's always been that way," he laughs.

His desire to make her proud endures. But it was during that time, bouncing between households, when Brookshire got involved in the streets around San Bernardino and Los Angeles. He wasn't committed to the lifestyle at first, he says. Instead, he was drawn to the persona. He possessed a dangerously common mix of qualities he still sees in youth who grow up in low-income, low-opportunity environments—a lack of hope, a deep yearning for approval, and no belief they can succeed in anything else. That blend, he says, convinces many to "play gangsters" whether they want to or not.

"You don't have much of an identity to cling to," Brookshire says. "You really don't have nothing to be proud of. And so, the gangster life, it becomes what you hear at the dinner table, with your parents, teachers at school. Everyone knows the bad guys in the neighborhood. Everyone's fascinated by that."

Brookshire's path dead-ended in an Arizona prison. In his cell, he looked back on what he'd hoped his life would be—and grew suicidal. The sense that he'd disappointed his mother, now much older and living on disability, felt too heavy to bear. So he began penning a goodbye to her.

His plan never came to pass, in part because he couldn't stop writing. He estimates the letter ended up running more than 30 pages. In what was supposed to be his suicide note were his life's hopes and regrets, released on the page as he faced down decades of incarceration. He also began writing about his life after prison.

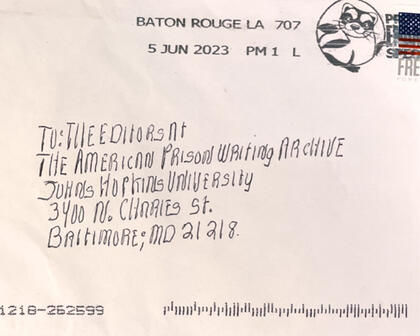

He didn't know it at the time, but his writing would connect him to that future, beginning his journey of laying out a detailed post-release plan that he follows to this day. Anyone can read some of them: More than 40 of his letters and essays live in the American Prison Writing Archive.

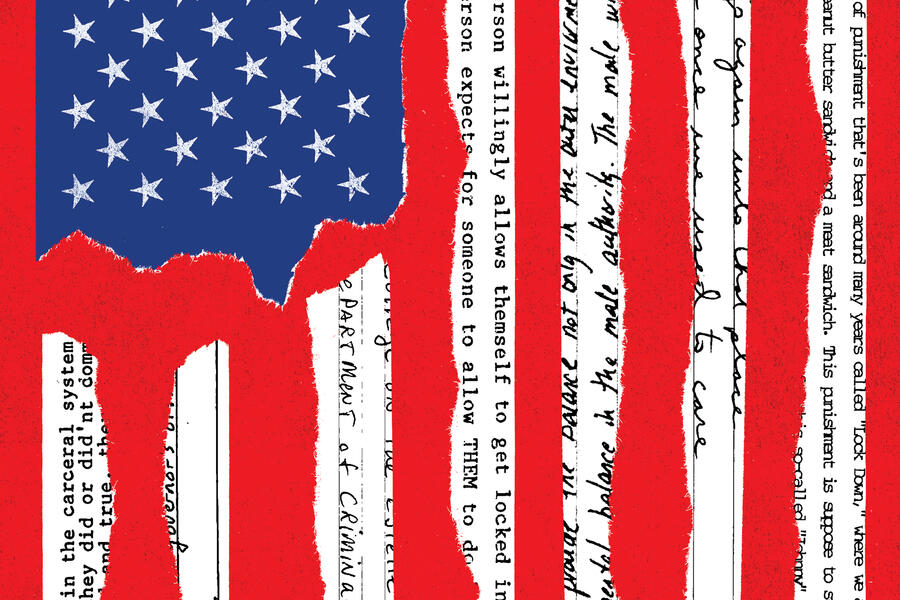

Now housed at Johns Hopkins University, the digital archive hosts nearly 4,000 pieces, each submitted by an incarcerated writer. It offers an unfiltered glimpse into the massive and troubled United States prison system, one that prison corrections departments often work diligently to keep from public view. And while such a collection might sound dispiriting, the writings showcase a panorama of human feeling and complexity—the misery of watching one's individuality deteriorate, the joy of creating theatrical productions, the strangeness of Sarah Palin making a prison visit—much of which is missing from common media narratives about prison.

"There's a body of expertise and beauty and creativity and ways that people are able to be keen observers," says Vesla Weaver, a professor of political science and sociology at Johns Hopkins and the archive's director. "They have unmatched insights into the world because they've lived at the receiving end of institutions that often fail them and have had to build from within those crevices ideas, aspirations, new ways of surviving, ways of giving back to one another."

Used by researchers, educators, advocates, and anyone interested in learning the realities of prison, the archive offers a home for those who rarely have a chance to express themselves to be valued and—ideally—understood. The writing serves as prison oversight and human insight, a window into the system and the souls.

"I literally shed tears when I first saw my writings inside [the archive]," Brookshire says. "The only way I can describe it is 'humility' because I know the person I was, and I know where I was at when I wrote those exact words."

The archive's creation began in 2006, when educator and author Doran Larson started a writer's workshop in Attica, the infamous upstate New York prison. Though men often came and went from the writer's group because of releases, transfers, or disciplinary problems, Larson remembers "a core of about seven or eight men that kept coming back."

"And that's really what kept me coming back: their consistency and dedication to the work," he recalls.

Exposed to these deeply emotional and creative works, Larson crafted an undergraduate course on American prison writing at Hamilton University, where he's a professor of literature and creative writing. During summers spent reading at the Library of Congress, he found little reflecting present-day prison life.

"The textbook I wanted to use basically didn't exist," Larson says.

Bereft of options but convinced of the quality of the work, Larson put out a call in 2012 for writing submissions through Prison Legal News, a publication distributed inside. He received 154, turning more than 70 of them into the book Fourth City: Essays From the Prison in America (Michigan State University Press, 2014).

The book's release didn't stop the submissions. Around half a dozen arrived each week, creating what Larson describes as "an ethical problem": a growing collection of writings with nowhere to put them.

"People would put in their cover letter: 'I know the deadline's passed. I know you're not going to be able to publish this. I just want someone to hear my story.'"

From these submissions, the American Prison Writing Archive began. Initially hosted at Hamilton, the project survived for years with a small staff and a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. As the archive grew, it became clear that while Hamilton valued the project, the liberal arts school simply didn't have the resources to keep it going.

Larson began searching for other possibilities. Around this time, colleagues of Larson's received a grant from the Mellon Foundation to launch a digital humanities project. Armed with both funding and a thriving archive, he just needed an institutional partner.

Enter Vesla Weaver.

For years, Weaver had studied prisons as an essential space for understanding U.S. democracy. Despite being taught politics that valued freedom, Weaver saw a huge portion of the country facing intense repression.

"The lived experience of the people I was talking to basically had no resemblance to the things that were being taught in American politics textbooks," Weaver remembers. "And at that time there wasn't even a mention of incarceration or prisons as a crucial site of the deployment of state power."

The two academics paired up, with Larson as the program executive, Weaver as the director, and Johns Hopkins as the new home.

JHU now hosts a one-of-a-kind collection, "a living archive" as Larson calls it, which gathers work not easily accessed. But its value runs deeper than that. Exploring the array of entries—essays, cultural criticism, poetry, and more—exposes one to an incredible breadth of experiences and emotions not often seen in portrayals of prison.

"I wish you could see into the hearts of these actors and poets," Beverly Jaynes wrote in 2017 of theater and poetry classes she took inside the women's prison in Vandalia, Missouri, "to see their gained self-confidence from meeting challenges and reaching goals, to see their joy in understanding their ability to take direction with self-discipline, to see their bonding and how far they've come together in personal growth."

In "Federal Felines," from 1993, the archive's oldest piece, writer John L. Orr chronicles a tense stare-down with another prison resident at the Federal Correctional Institution Terminal Island, a low-security prison sticking out into the Los Angeles harbor. That resident, it turns out, is a cat, and the rest of the story unfolds as Orr's tender reflection on the surprising fulfillment of caregiving and the meaning found in moments free from society's labels.

"The nursery became a refuge for me," Orr writes of the cats' makeshift home. "An island on an island, and l retreated to its confines every chance I got: writing letters, reading, and just to escape the desolation of the general population. Slowly the kittens accepted me and occasionally used my legs as scratching posts if I didn't flinch. I guess I was part of their playground."

Many of the reflections in the archive grapple with the full complexity of incarceration, with dozens of writers pointing out the absurdity of violent, destructive institutions advertised as spaces for personal growth and reform.

Writing from the notoriously violent Alabama prison system, Donald D. Hairgrove in a "A Single Unheard Voice" broke down the miseries the system inflicts—from violent officers to deprivation of contact—while presenting it to the taxpaying public as a place for people to change.

"Far from rehabilitating or 'correcting' past errors, it constitutes a setting that helps drive people to anger, frustration, and despair," Hairgrove wrote in 2015.

At the same time, writers wrestle with their own mindsets, investigating themselves and their behaviors.

"Through Zen Buddhist meditation and contemplation," writes Diana W. in an essay from an Alaskan prison, "I have learned about myself—all the ugly, dark, and scary stuff: the fear, self-pity, anger, and deep sadness; and, surprisingly, some good stuff too: a sense of humor, intelligence, compassion, and true remorse."

Brookshire himself embodies this experience, writing about society's vicious treatment of the poor and mentally ill in one passage, then saying he deserved consequences for his behavior soon after. Yet he, like many incarcerated people, says that none of what he needed for meaningful change could be found inside.

"It's not an environment for learning," Brookshire says, "It's not an environment for teaching, and it's not an environment for growing. You have to make it an environment for growing."

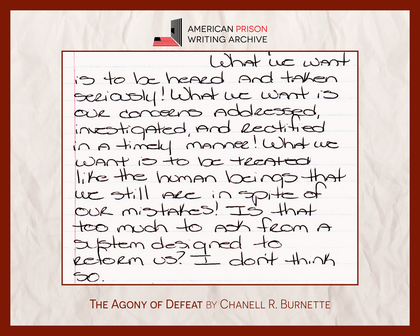

That tension—between understanding the need for rehabilitation and experiencing its near impossibility inside—is perhaps best encapsulated by Chanell Burnette.

"I am simply a human being who has made a very costly mistake," she wrote from Virginia in 2019, "and am making the best effort to understand why we all do the things that we do … and also a desperate attempt to open the eyes of those in charge of passing judgment on us."

If there's a throughline in the archive, it's a powerful desire to be viewed as human. Piece after piece beckons the reader to understand incarcerated people as people, complete with the same talents, desires, and flaws as everyone else. This acceptance, many pieces assert, would make the public's faith in punishment much harder to sustain.

That punishment extends to prison communication itself. Ostensibly to prevent contraband from entering facilities, prisons and jails have increasingly adopted mail scanning: a process by which the system itself or a third-party contractor digitizes mail and sends it to the incarcerated person, often completely disposing of the original paper copy. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, at least 14 states deployed the practice between 2017 and 2022 alone. The federal system and many local jails have done the same.

This crackdown extends to reading as well, with many facilities prohibiting books sent by anyone other than approved vendors, or banning books entirely. PEN America, a nonprofit supporting free expression, analyzed the 28 states reporting information on banned books and found more than 22,000 titles banned in Florida's prisons and more than 10,000 in Texas'. These restrictions are growing more common, decreasing the ability of incarcerated people to communicate with loved ones, limiting their options for positive forms of expression, and cracking down on a key method of prison oversight.

"It's all part of cost-cutting and efficiency," says Yukari Kane, co-founder, CEO, and editor-in-chief of the Prison Journalism Project. "I think part of the impetus for that was the labor shortage [in prisons] after the pandemic. And as they've done that, they've realized that doing that allows them to control information a lot more."

The Prison Journalism Project was also inspired in part by the pandemic. Kane and PJP co-founder Shaheen Pasha were teaching journalism in prisons. When prisons and jails cut off visitation at the dawn of the pandemic, information from inside became even more scarce, all while the virus and staffing issues were decimating facilities.

PJP's newspaper and the stories it helped place in other outlets became one of the few ways the outside world learned of the devastating effects of COVID-19 on prisons.

Like many with incarcerated loved ones, Mc?kenna Deluca sees access to literature inside mingling the political and personal. As co-director of the Claremont Forum's Prison Library Project, she helps ship thousands of books each month to incarcerated people and sees firsthand the power of creativity inside.

"My dad was incarcerated when I was in high school," Deluca says. "He's since passed away, so I'm kind of doing this in memory of him. But also, when he was incarcerated and got out, he kept saying [he'd] not gotten involved with gangs or any other kind of malicious activity because he was reading all the time."

Increasing opportunities for education and expression are how society shows the people inside we still care, she says.

Even when those inside can find time and space to consume or create literature, its survival is not guaranteed.

Brookshire remembers "meticulously" writing pages and pages of deeply important thoughts, only to have them destroyed during a confrontation or a move.

"Sometimes we've had people send us a 200-page manuscript, and they say, 'I know that you may not be able to take this. Please don't send it back. It'll get destroyed,'" Weaver says.

Bringing visibility, security, and respect to prison writings is a primary goal of both Weaver and Larson. For Larson, the American Prison Writing Archive represents a sharp turn from seeing incarcerated people as problems to seeing them as a vast resource of creativity and experience, able to help society answer difficult questions.

"What the archive is seeking to do is to turn that around and say, This is a pool of incredible human resources for understanding not only the criminal legal system but literally every factor that leads people into this system," Larson says.

For Weaver, it's a way for the country to look at itself, to question rigorously whether we live up to our ideals.

"We'll be able to have a collective testimonial account that wasn't focused on one prison. It was a mass of writing that is better than any social survey poll of incarcerated people. I mean, the power of the archive is that," she says. "We don't tell people what to write about or what to say. And yet, through their writings, we have amassed an incredible documentary evidence base."

That sense of treating incarcerated people inside as unique personalities, rather than as a monolith, infuses Deluca's ambitions, too. She's seen change come about when "we looked at this one individual—if we could change this person's life and they could change that person's life—more on a one-on-one basis, instead of a collective 'you' or 'other.'"

If the crackdowns on prison communication make prison seem even more isolated, they also make the archive and other endeavors to give prison writers outlets that much more valuable. The archive is part of a small but notable boom within prison journalism and writing, with new organizations, such as PJP and Empowerment Avenue, training and publishing prison journalists. Outlets like Prism and The Appeal also offer publishing opportunities. The Marshall Project launched News Inside, a free publication for incarcerated people, and recently prison newspapers have started growing again.

Still, the challenges seem to grow as the archive does.

A team of eight now runs the American Prison Writing Archive, opening about 700 submissions per month and responding to each. Together, they navigate thorny ethical questions.

"What happens when a journalist comes along and wants to republish some of the work and the person has died?" Weaver asks. "Or they're transferred to the prison hospital because they've been beaten up or neglected, or we can't get back in touch with them for whatever reason? What happens when what they write could expose them to further retaliation and violence?"

Larson and Weaver both teach with the archive. For those inside, its value keeps revealing itself to new writers.

What Brookshire wrote continues to guide his life, starting all the way back to the letter to his mother. Together, his writings collectively chronicle his new understanding of society and the "elaborate charade of the so-called gangsta's code." And across nearly four dozen pieces, he painstakingly plans his life after prison. Slowly, the obstacles before him seem more solvable. Possibilities inch closer.

Also see

Now a peer support specialist with Community Bridges, a nonprofit in Arizona, Brookshire hopes those who discover the archive will see what he calls the "absurdity" of prison but also the power of providing people inside with an opportunity.

"It gives life. That's life for people who are in a dark place," he says of being in the archive. "Just know [the writers] are sitting in a room where they're supposed to be depressed, where they're supposed to be downtrodden, where they're supposed to be melancholy. But yet that beautiful creation came from their head through their arms through the tip of their pen onto that paper. And that's what you read. And that's beautiful to me."

Larson and Weaver say the archive doesn't need a hard sell. Just give it a try, and you'll understand why it's needed. "I tell my students: It's like walking into a dark room that's full of furniture, and you have to arrange the furniture," Larson says. "But first you're going to have to bruise your knees badly by just running into it. … When they go into the archive, they're getting their moral compasses so thrown off balance because it just doesn't fit the world that they believed they operated in."

The archive also represents a microcosm of the country: birth and death, meeting and parting, violence and redemption, labor and segregation, attempts at change both successful and thwarted.

"It's so much more than just, 'This is the injustice of these institutions,'" Weaver says. "It's people who have seen a range of failures, even before they got to prison. So to me, it's a story of America—all wrapped up in this one place." For others, it's something they carry with them.

"I know that [my plan] would always slip my mind if I didn't have it written down," Brookshire says. "If I forget, I could look at my master plan. It'll always be posted in that archive. And I'm literally living it. Now I'm just living what I wrote."

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged writing, prison-industrial complex, incarceration, prison reform