For 50 years, Howard Bartner, Med '58 (Cert), '69 (MA), commuted from his home in Bethesda to Baltimore, to teach ophthalmological illustration in the Department of Art as Applied to Medicine at Johns Hopkins. Because Bartner had a history of vertigo, the commute usually involved his wife, Elayne, and a colleague from the department, who together performed a kind of baton-pass of the beloved professor.

But even with such diligent delivery, Howard was almost always late, according to a former student who is currently director of the AAM department, Cory Sandone, Med '86 (MA). "Howard had his own sense of time," Sandone remembers, before clarifying. "He was never on time, but he was always present."

Although Howard died in 2018, his legacy will remain very much present in the department. His family recently established the Howard C. Bartner Scholarship, which will support deserving students as they work toward their Master of Arts in medical and biological illustration, one of only four programs of its kind in the country.

Howard Bartner was born in 1931 in New York City. According to Elayne, both Howard and his twin brother, Walter, were "very artistic." In 1954, Bartner earned his bachelor's degree in fine arts from Temple University, intending to be an art teacher. Medical illustration wasn't on his radar until an acquaintance of a roommate mentioned the program at Hopkins. Bartner scheduled an interview with Ranice Crosby, Med '40 (Cert), A&S '73 (MLA), then director of the department. She was impressed by Bartner's portfolio but told him he would need more science credits to be admitted. Back to Temple he went to earn his Bachelor of Science degree.

In 1955, Howard began his studies at Johns Hopkins, where his skill for medical illustration quickly became apparent. "When artists speak about the quality of another artist, we often use the adjectives 'creative,' 'gifted,' or 'talented,'" colleague and AAM Professor Emeritus Gary Lees said in his eulogy for Howard. "When speaking of Howard's artistic qualities they are elevated to 'consummate' and 'superlative.'" Sandone says Howard's illustrations were "breathtaking in their apparent ease of execution," even though each piece "had emerged from a meticulous process of measuring and sketching and a laborious series of revisions for accuracy and clarity."

At Hopkins, Howard hit his stride professionally—and personally. During the second year of the program, Howard attended a lecture on the Dead Sea Scrolls, where he asked a friend to introduce him to the "blonde lady" who caught his eye. That blonde lady was Elayne. She remembers the first flowers Howard gave her, and how, when she lamented their fading, he painted a watercolor of the bouquet, to preserve it forever. The painting still hangs in her living room today.

After earning his certificate in medical illustration from Hopkins in 1958, Howard landed a position at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, where he and Elayne moved their young family. Five years into the job, at age 32, Howard was promoted to chief of medical illustration, a position he held until his retirement from NIH in 2000.

Around the time of Howard's NIH promotion, his old friend and mentor Ranice Crosby called. The instructor for the ophthalmological illustration course had retired; Crosby wanted Howard to take her place at Hopkins. During the next five decades, Howard would teach 235 students, including 25 from other programs who sought Howard's renowned instruction.

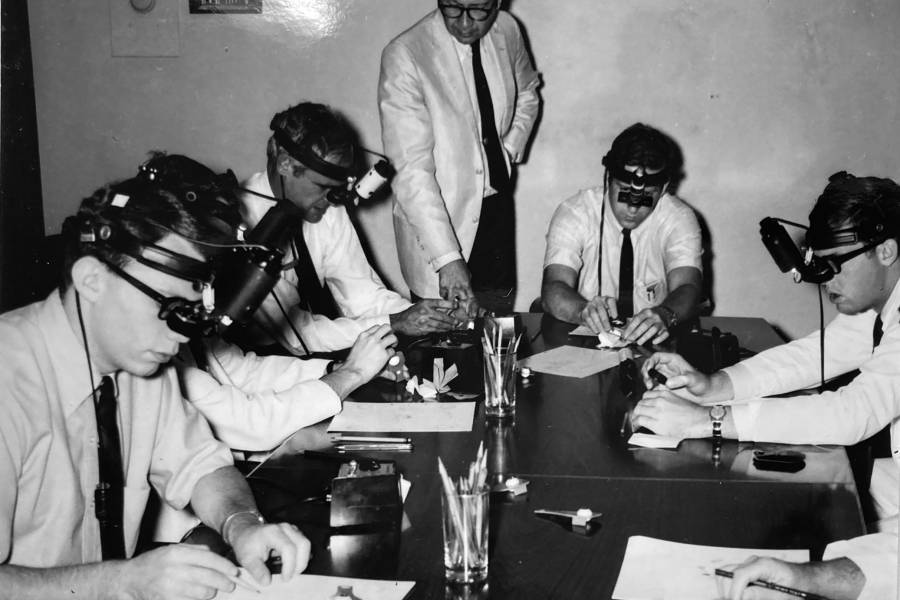

That ophthalmology course—the final class of the program—became a rite of passage. "The best thing about the course was that Howard's teaching reinforced all of our fine arts training," says Sandone, "reminding us that despite all the anatomy, medical knowledge, and understanding of science we had mastered in the program, we were artists at the core."

To pass the course, students had to complete surgical illustrations after observing a procedure at the Wilmer Eye Institute and consulting with the surgeon. But arguably the most the nerve-wracking part of the assignment was Howard's critique, which he offered over lunch at his home in Bethesda, making sure "all details of the surgery were understood and the story was arranged in the clearest possible fashion," according to Juan Garcia, Med '95 (MA), another former student of Howard's and an associate professor in the department.

Howard had high standards for his students, but he held himself to the same ones. When the AAM department approved a master's degree, Howard completed a master's thesis in 1969, purely out of devotion to his craft. Elayne recalls that one of Howard's proudest moments was receiving AAM's Max Brödel Award for Excellence in Education surrounded by 40 of his former students. "I know how much he loved the department," she says.

Indeed, after his first week on the job at NIH, back in 1962, Howard wrote to Crosby, "I think only after you leave Hopkins do you finally realize how adequately you've been prepared."

Thanks to the Bartners' generous gift, many more medical illustrators will come to enjoy that same realization.

Posted in Alumni