When Tracy Walder decided to pen a memoir about her six years with the CIA and FBI, her book agent sent her the names of more than a dozen professional writers who could help. The one who caught her eye was Jessica Anya Blau, A&S '95 (MA), author of four novels about young women in extraordinary circumstances, including a college student who finds herself on the run with a Wonder Bread bag full of cocaine. "I remember Googling the crap out of Jessica, finding her books, and loving them," Walder recalls.

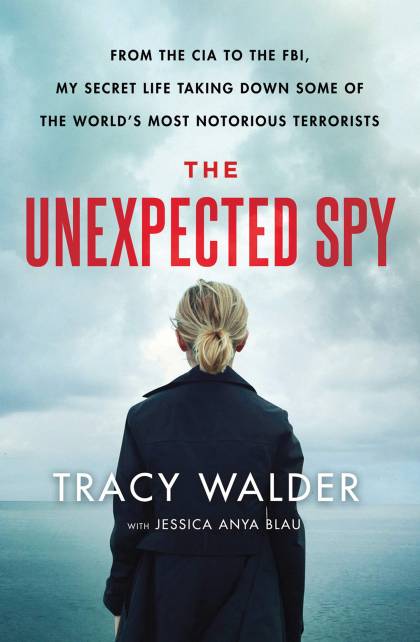

Walder called Blau to sketch out the basics of her story, which would become The Unexpected Spy (St. Martin's Press, 2020). As a senior history major at the University of Southern California, Walder thought she might become a teacher. One day, she biked from her sorority house to a campus job fair and on a whim dropped off a résumé at the CIA table. To her surprise, she was invited for a series of interviews and was offered a job as a staff operations officer upon graduating in 2000. She started in the agency's counterterrorism division, studying grainy satellite images of the mountains, caves, warehouses, and safe houses where al-Qaida operatives gathered.

By chance, she was assigned to work on a highly classified program—she is barred from giving its name—about two weeks before September 11, 2001. The terror attacks brought new urgency to the agency's work, as Walder and her team hunkered down in a room she calls "The Vault," scrutinizing drone images of suspected terrorists to deduce their networks and plans. President George W. Bush often stopped by; CIA Director George Tenet would bring the team doughnuts and coffee, an unlit cigar dangling from his lips.

Walder spent many months at an undisclosed location in the Middle East. She describes leaving an American military compound in the trunk of a car so as not to attract attention, then being taken to interrogate a terror suspect in a former warehouse. He offered her tea—although he had none—she handed him an orange, and she somehow managed to elicit vital secrets from him. She prevented several chemical attacks and raced old cars around a CIA training camp as part of a class nicknamed "Crash and Bang." After four years, eager to have a life outside of work and spend more time in the United States, she left the CIA and joined the FBI. There she says she was the victim of sexism, being denied deserved job opportunities, and left after a year and a half. She eventually began teaching at a private, all-girls high school in Dallas, where she established a class in national security and inspired dozens of girls to go into the field.

Hearing Walder recount her experiences during that first phone call, Blau was smitten. "It's almost like dating," she says. "We started talking and I was thinking, 'Oh my God, this is the coolest person I've ever met.' She's incredibly modest and doesn't have a sense of her greatness. As we talked, little details would come out that she didn't think were a big deal, like she would casually mention a bomb going off."

Those surprising moments continued to unfold over long phone calls and occasional meetings in Dallas, where Walder lives, and New York, Blau's home. Blau had previously ghostwritten four books, which she considers a good exercise in experimenting with perspective and voice. "It's liberating to write in someone else's voice," she says.

In turn, Walder made it clear that she wanted Blau to be a collaborator, not a ghostwriter, on Unexpected Spy. She poured out her memories in a Google document, and Blau molded them into a narrative. In time, their thoughts began to converge. In one passage, Blau wrote that Walder ate grapefruit at diner breakfasts with colleagues because she was afraid the strange hours she kept could lead her to contract scurvy—this was true, but Walder hadn't said it. "It was like she was in my brain," Walder says. Walder, too, found herself thinking more like Blau. She began to realize the sorts of anecdotes and details that would move the narrative along. "Jessica asks the best questions of anyone I ever met," she says. "She knows how to ask the question to lead you down a path you didn't know how to go down."

After eight months, the two had a draft, but the real challenge still lay ahead. "When you leave the CIA, you sign a nondisclosure agreement that anything you write about the agency has to be approved by the publication review board," Walder says. She was worried the agency would quash the project entirely. So when the draft came back heavily redacted, Walder was delighted it could be published. Blau, on the other hand, was despondent. "There were whole chapters that were blocked out except for one word," she says.

The women began work on a second draft. That, too, received substantial redactions, but Walder, Blau, and their editors made the decision to publish it as is, the bars of black scattered across the pages heightening the sense of intrigue. Among those who found Walder's story compelling is Ellen Pompeo, the director, producer, and Grey's Anatomy star. She purchased the rights to the book and is working to adapt it into an ABC series.

Walder and Blau still stay in close contact, chatting every day or so. To Blau, who is finishing work on two novels, Walder is equal parts patriot and feminist inspiration. "You can be a woman who likes the color pink and still be a badass," she says.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged book review, new releases, summer reading, summer reads 2020