I didn't know those gates could open. For 17 years, I've posed for many residency class photos in front of the massive, ornamental cast iron gates on Broadway, steps from the iconic domed Billings Administration building. But on the most beautiful March day that anyone could ask for, those gates were flung open. A man in uniform gestured to me to drive around the circle and stop at the tent under a magnolia tree. Beneath exquisite pink blooms, a woman in full personal protective equipment confirms my name—and then my COVID-19 test is performed.

Rewind to five days earlier, a Monday. I had just started a regular service week at the Johns Hopkins Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, where I was leading a group of trainees who were learning how to care for critically ill children. But this would not be a normal training period. The World Health Organization had just declared COVID-19 a pandemic. Schools and businesses closed. Our friends and families now mostly worked from home. But in a pandemic—no different from a snowstorm that brings everything to a standstill—we caregivers confront our calling to take care of the sickest patients in the region.

Morning rounds were conducted in a larger circle to achieve social distancing. Parents were asked to meet us outside the rooms to limit a patient's exposure to staff. We did everything we could to protect our little patients. The week pressed on, with the ups and downs that we are so used to in pediatric critical care medicine. By Friday, my shoulder aches seemed just a routine part of a busy week with long hours. Better safe than sorry, I thought, and went straight home to our guest bedroom without interacting with my family. The next morning, I got a text from a colleague I had worked with closely all week, who had a nagging sore throat. "I'm positive," he told me. Suddenly, the muscle aches weren't just a regular week's toll.

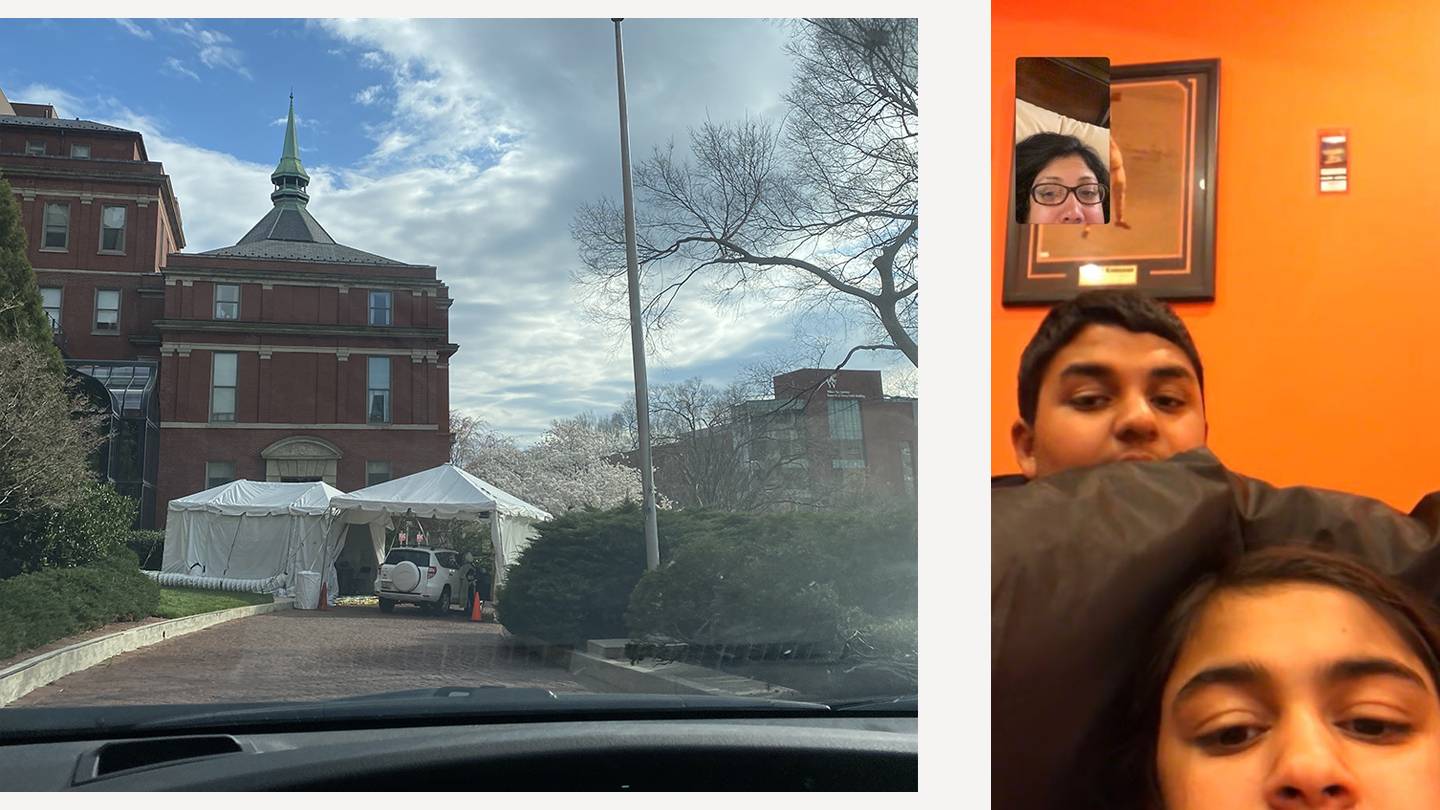

Image caption: Left: Kudchadkar waits to be tested for the coronavirus at the drive-through testing facility set up on the university's East Baltimore campus. Right: Craving togetherness, Kudchadkar and her children FaceTime during her illness. But the screens are no match for real connection, the family soon learns.

Image credit: Courtesy of Sapna Kudchadkar

And that's how I found out the gates do open. After my nasal swab, I went home and isolated myself a second night, just in case the test came back positive. The fever and cough started a few hours later. Within 24 hours, what I already knew was confirmed, and my husband set my room up for quarantine. He gave me a large garbage can, a mini microwave, a yoga mat, and a case of bottled water to get me started. A tray outside my room for meals. After all, I had to protect my family from getting sick. Even before my illness, I would change my clothes and shoes at the office, and shower first thing when I returned home. My kids already knew no hugs were allowed until my decontamination routine was complete. But what had been a daily 15-minute process was now 14 days of no in-person contact. My daughter lamented over our first FaceTime of quarantine: "I didn't even get to hug you this morning before you left."

Isolation life started out pretty easy. My world became a series of FaceTime, Zoom, Words With Friends—all screens, all the time! My 11- and 14-year-old are used to me traveling, so how hard could this be in the same house? I was blessed, compared to many, to have a "mild" form of disease. I could get lots of rest between bouts of overwhelming fatigue, chills, and coughing fits. What I wasn't expecting was the weakness. By Day 4, even five minutes of gentle yoga felt like a marathon. By Day 5, my sense of smell had disappeared. On Day 6, I began posting about my experience on Twitter, using #SapnasCOVIDDiary to provide my peers and the public with personal insight about a disease impacting all of us. And, I realize now, I was writing to cope with my own emotions. By Day 9, my symptoms were resolving, but I started feeling a sense of despair that I couldn't place. That same day, my daughter broke down crying while we read a book together on Zoom. "I thought I could last 14 days, but this is really, really hard," she sobbed. And then it hit me—I was suffering from a loss of human touch.

Human touch. It's amazing how things come full circle. When I'm not taking care of kids in the hospital, I research how early physical rehabilitation can improve their outcomes. In fact, every trainee who works with me knows that all children in the PICU, no matter how sick, should be prescribed "therapeutic cuddles." Human touch is the essence of being—no matter how young or how old you are. So on Day 14, my "big reveal," that first cautious hug with my son (how can I be sure I'm not still infectious?) felt like pure bliss.

Image caption: Left: Kudchadkar's family has participated in volunteer efforts across the university, including, here, preparing hand sanitizer bottles for distribution among Johns Hopkins health care workers. Right: Kudchadkar herself has donated her blood plasma, which can be used to prevent and treat COVID-19.

Image credit: Courtesy of Sapna Kudchadkar

I was one of the first 200 cases of COVID-19 diagnosed in Maryland, and a lot had happened in the intervening 14 days. Two hundred cases became 3,000. The disease was fortunately still largely sparing children, so I was deployed to assist my adult ICU colleagues. Secretly, I was both thrilled and nervous. I would finally have a chance to make a difference on the front lines. But was I ready? Was I immune? How would my colleagues feel around me? My first day attending in the adult unit, my team introduced themselves. There was a surgery resident, a cardiac surgery nurse practitioner, a transplant nurse practitioner, and me, a pediatric ICU physician and anesthesiologist. We may have seemed like a motley crew, but what happened was extraordinary. It was as if we had worked together for years, teaching each other from our respective expertise and doing our best for sick patients. We quickly learned through our own eyes that COVID-19 can be unpredictable: sudden cardiac arrest, heart failure, and blood clots in the lungs.

There were also the predictable, short- and long- term physical and cognitive impacts, but worse than we had ever seen before.

With COVID-19, the game is very different. Our usual intensive care rehabilitation is limited by the need to isolate patients in their rooms. With no family allowed to visit, and staff in masks, gowns, and gloves 24/7, patients completely lose human touch. The elderly woman with dementia, the 40-year-old marathon runner. No one is immune to the severity of COVID-19 and the isolation it brings. We learned to revel in the bright moments and tried to fill the role of family. I recall talking with Mrs. F about her favorite show Gunsmoke (which my parents also love) and ordering Mr. M's favorite Indian comfort food. But the dark moments are overwhelming. It's hard to forget holding the iPad for a man's last conversation with his wife or comforting a daughter who can't be with her mother in her final hours. In addition to deep sadness in those moments, I came to terms with an unexpected emotion: survivor's guilt. Why was I so lucky, when so many weren't? I still struggle with this question to this day. There may never be an answer, but there is a way to make it better.

Surviving COVID-19 has spurred me to look for every way possible to give back, to pay it forward. My kids and I now volunteer to make personal protective equipment for health care workers. I curate the latest COVID-19 research for my colleagues, both locally and on social media. I enroll in every research study that I can find to advance our knowledge of and therapies against the disease. And I donated a liter of my plasma, rich in COVID-19 antibodies, to help a critically ill patient who wasn't as lucky as me. Most importantly, I go back to work each day, to fight this disease for the patients who continue to come through our doors.

Posted in Health, Voices+Opinion

Tagged coronavirus, covid-19