I've never seen the cinematic version of Charlotte's Web. I also skipped Harriet the Spy, The Secret Garden (movie and TV), Pippi Longstocking, and Tuck Everlasting. I scorned Shirley Temple in The Little Princess and Selena Gomez in Ramona and Beezus. As a child of the 1970s and '80s, I couldn't avoid NBC's Little House on the Prairie—though a shirtless Michael Landon rendered the series unrecognizable, anyway—and despite my love for Laura Dern, I have yet to see 2019's Little Women. (I skipped the 16-odd other adaptations, too.)

Image credit: Courtesy of Lizzie Skurnick

It's not because I'm a purist, or a stickler, or I don't think books should be made into movies. I love both versions of Jaws. But when it comes to the books I read as a child, I just can't tolerate it.

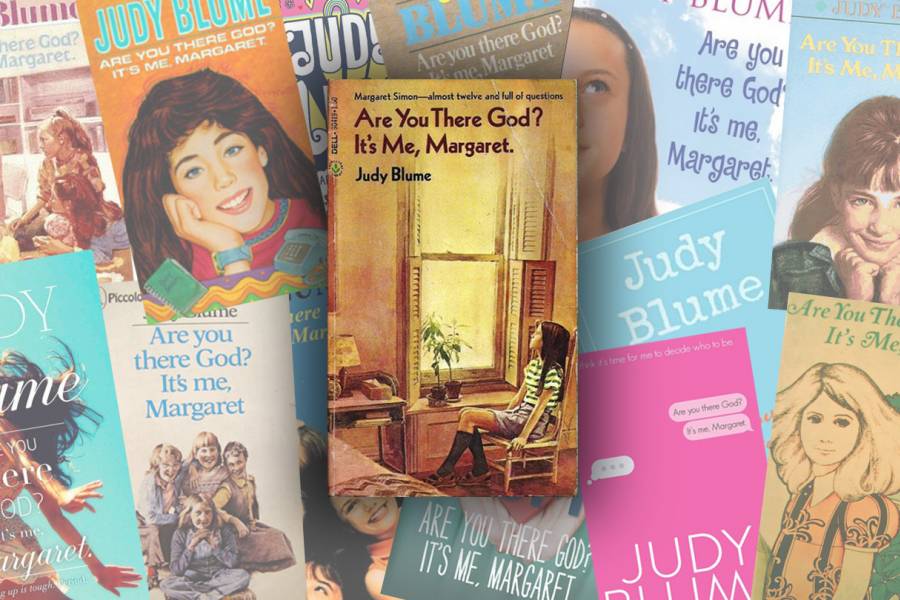

You will not be surprised to hear that I greet the news that Judy Blume has finally sold the film rights to Are You There God? It's Me, Margaret with, to put it mildly, mixed feelings. The book, at 50, is only four years older than I am. And I worry that any rewriting of the book will become, to some extent, a rewriting of my childhood.

When you are a child, reading fuses into your own experience. The books I read as a girl, how characters looked, how they sounded, how the book felt, were a particular alchemy of my experience and imagination.

I already have my Margaret. She is on the cover of the 1981 Laurel Leaf edition—the one I read to shreds—and she is rendered with Hans Holbein–like precision, down to the buckles of her sandals. In my head, the house she moves to in New Jersey looks suspiciously like the one across the street from my childhood home in New Jersey, and her mother like the lady in the "Palmolive: Softens Your Hands While You Do the Dishes" ad of the time. I can even see the distinct way her grandmother holds her purse as she tells Margaret: "If Mohammad won't come to the mountain, the mountain will come to Mohammad."

Readers reify all novels like that, bringing text to flesh. I can see my secret garden's ivy-covered door, my Ramona's haircut, the kitchen where Harriet eats her tomato sandwiches. I set wardrobe and lighting, choose the location and soundtrack, do my own casting and blocking. Not even a visit to the actual house of Louisa May Alcott would disabuse me of the garret in my head.

Today's young adults have a relationship with their books that is unimaginable to the readers of my era. A glut of streaming services and studios has made film deals from bestselling YA books a foregone conclusion. Just look to Harry Potter, or The Hunger Games, or the forth?coming Binti series on Hulu, based on the books by Nnedi Okorafor. For readers today, part of the experience is to see the meticulously described details come to life, whether in a movie or a visit to Diagon Alley at Universal Orlando Resort.

This collective experience is not entirely new. In 1841, American readers swarmed ships carrying the last installment of Dickens' The Old Curiosity Shop, begging British sailors to tell them whether Little Nell was dead. If Dickens fans could have visited an animatronic Nell on her deathbed, they would have—and then swung by the gift shop.

The difference is that now the reader takes an active part in the official adaptation. YA authors announce their HBO, Netflix, and Hulu deals to followers on Twitter, and fans stream into the comments section with casting suggestions and congratulations. That kind of collective power was unthinkable when Margaret was published. Then, there was no expectation the book we were passing around at sleepovers would be made into a movie. (Especially if that book was Forever.) We readers certainly had no influence. An author barely did. As Lois Duncan joked after she saw the bloody remake of her 1973 thriller I Know What You Did Last Summer, she had to sit to the end of the credits to make sure she was in the right theater.

Also see

But Blume has released the rights at a time when it's finally standard for a YA writer to be a consultant to the project's script, if not a co-writer. (As Okorafor will be on Binti.) Margaret is a far more elusive creation than a Golden Snitch, but that doesn't mean her movie version will be an insult to the original. Who's to say that now, whatever and whoever Margaret becomes, she won't be powerful in her own way?

Still, there is one question every reader will want answered. In 2006, Blume updated Margaret's Softie pad with a self-adhesive maxi, apparently to make the book more accessible to modern readers. An uproar ensued. Now, we will all want to know—how will Margaret's menarche be updated? I can already see the commenters storming Twitter: "@judyblume, please tell me Margaret's pad still has a belt" and "@judyblume, can she use Thinx BTWN?" For the first time, the answer to that question alone might get me to the theater.

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged personal essay, judy blume, summer reads 2020