The Kit Kat Klub dancers are going nuts. They slink around the stage, kick their legs into the air, and twirl around. Two dancers cradle briefcases ostensibly full of cash. All the while, their club's emcee sings about money's ability to buy happiness, nice things, and temporary companionship. They finish this catchy love letter to everything being for sale with the emcee standing center stage, encircled seductively by the dancers.

At least, that's the idea. The group of about 10 young men and women rehearsing the choreography for the song "Money" in the musical Cabaret are discovering it's easier to aim for a ruckus than it is to raise one onstage. They're gathered inside a black-box theater on the Homewood campus on a Saturday afternoon in March, four weeks before the Johns Hopkins Barnstormers opens its spring 2019 musical. This production marks the 100th anniversary of the undergraduate-run theater company's founding, and they're going big for the occasion. They're building a two-story set inside Swirnow Theater, the company's main stage since 2001. They've hired a few Peabody and professional musicians for the 13-member pit. All told, more than 60 students are working on the production in some way.

Director Max Hunter is the only nonstudent at rehearsal today, hired by the Barnstormers nine-member executive board in February. He watches from one of the theater's seats and asks Samantha Albstein, the company president and Cabaret's choreographer, "How are you feeling about that?"

Albstein, who also plays one of the Kit Kat dancers, grimaces. "Not good," she says.

Stage manager Shireen Guru sits stage front at a table with a laptop and what looks like a copy of the script and score absolutely overrun with notes. She calls for a quick break, just long enough for the cast to grab a swig of water and get comments from Hunter and Albstein. The cast, clad in combinations of sweats, T-shirts, tights, shorts, sneakers, and dance heels, falls out of formation. Some grab phones, others lean against parts of the set. Another 10 or so undergraduates are scattered around the theater's seats. Some watch the rehearsal, some click and scroll through smartphones, some have laptops open and do homework. They're the student producers and members of the backstage tech and build crews. The two-story set isn't complete yet. The stairs to the second floor aren't load-bearing, so tape keeps actors from climbing them. Some parts of the set are painted black. Recently. Two members of the build crew see the actors leaning up against it. One asks, "Do you think that's dry?" The other shrugs. "Probably?"

In some ways, Cabaret, the 1966 musical about party people in decadent 1930s Berlin, is an old-fashioned, razzle-dazzle musical with lots of singing and dancing. It follows Cliff (played by Zach Galvarro in the Barnstormers production), an aspiring American writer who, shortly after arriving in Berlin, falls in with the freewheeling Sally Bowles (a powerful Sophia Diodati), an English dancer at the Kit Kat Klub who never wants the party to stop. The nightclub promises a never-ending variety of sex—guy and gal, guy and guy, guy and gal and gal—booze, drugs, and more booze. All this debauchery takes place as the National Socialist German Workers' Party emerges in the story's background.

It's a difficult musical for any company to pull off because the tonal shifts it requires demand thoughtful attention to details. Moving from nightlife to Nazis isn't something to be handled lightly.

A theater's production process can look like an only slightly organized runaway train from the outside. A bunch of wood, paint, and stuff gets turned into a set. Thrift store clothes, fabric, and thread become a wardrobe. And a group of people who start out reading lines from a photocopied script butterfly into flesh-and-blood characters living during a precarious time. Postures are tweaked, accents refined. Emotions explored, honed, and unleashed.

Image credit: Frank Hamilton

The Barnstormers, a group of roughly 125 undergraduates, do this five times over an academic year. And by "this," I mean everything associated with budgeting, managing, programming, promoting, and running a theater company. Its executive board submits a budget proposal for the school year to Student Activities Commission—in recent years, around $12,000 total—and, once approved, the students do everything else.

"If the Barnstormers were to say, 'We're not doing any more plays,' no administrator or anybody would say anything to the contrary," says Nick Xitco, the organization's publicity manager, who also plays keyboard and accordion in the Cabaret pit. "The only reason we continue doing stuff is because we love it and love working together."

Xitco is a Class of 2020 computer science major, and like a majority of Barnstormers, he's not considering a full-time theater career. Hopkins doesn't have a conventional theater or performing arts department—in 2004, actor John Astin, A&S '52, a former Barnstormer, reestablished the Program in Theatre Arts and Studies, which offers a minor—and the university doesn't typically attract young people interested in pursuing such a career path. While some Barnstormers have forged theater careers, on the whole, they end up as doctors, engineers, entrepreneurs, lawyers, politicians, professors, researchers, scientists, and writers.

Doing theater helps them get there. In conversation with 20 current and alumni Barnstormers—they use the name to refer both to the company and themselves—they run through a list of things they've learned through the company: budgeting, collaboration, conflict negotiation, leadership, peer mentoring, public speaking, time management. These skills are learned by doing, and before Cabaret's opening night, the cast and crew will put in more than 250 hours exercising those skills during rehearsals, set building, and production meetings. That number doesn't include the individual time cast members put into creating the weekly rehearsal schedules around everybody's class times and commitments, or the time publicity manager Xitco puts into creating posters and online advertisements, or what Albstein puts into choreographing the show for a range of skill levels.

Students, however, don't get involved with Barnstormers to pad re?sume?s. And understanding why students devote so much of their lives to making theater goes a long way toward understanding how a performing arts organization has lasted a century at America's first research university. Students, especially Hopkins students, don't invest untold hours of their free time into an activity unless it means something to them.

Following the brief break, Albstein works on the choreography with the women dancers, and Hunter takes the two male dancers and emcee (Frank Guerriero) into the lobby to go over their parts. Albstein and the women walk through a few tricky moves, taking time to figure out where to orient themselves onstage. About 15 minutes later, Hunter and the guys return, and they go through parts of the song a few more times before running through the entire thing. They're rehearsing along with a recording, and only kinda/sorta singing along. The result is much better this time.

"That was great," says stage manager Guru. "Now, do it again."

Company president Albstein, A&S '19, loves musical theater, and did theater in high school, mostly musicals. (Note: All titles refer to the 2018-19 year; a new board was voted into office in the spring, and it will oversee the 2019–20 season.) She knew about Barnstormers because her brother went to Hopkins, and she found out the company does a musical every spring from its website. "To be honest, I was sort of obsessed with Barnstormers before I even got here," she says.

Albstein double-majored in math and psychology with minors in music and theater arts, and her story is similar to those of a number of current and alumni Barnstormers I interviewed: a young person who had done a fair amount of community or high school theater, who wasn't going to study theater in college but still wanted to do it. They learn about Barnstormers before arriving at Hopkins or when they get to campus, and find their way into the group during their first year. The company becomes their main extracurricular activity and social group. And they love it—and their fellow Barnstormers—with the passion of a thousand suns.

Technical director and rising senior Laura Oing leads the crew that built the Cabaret set; she got involved in theater's tech side in middle school because she didn't consider herself a performer. Octavia Fitzmaurice, A&S '19, acted in high school and wanted to continue performing at Hopkins; with Barnstormers, she's also directed a few of the Freshmen One-Acts.

And vice president of professional productions Julia Zimmerman, A&S '19, started working at a community theater in her Connecticut hometown when she was 10. She was a backstage runner who flitted between stage and dressing rooms to fetch actors. At 11 she became a production assistant for The Wizard of Oz, which, she says, "mainly meant being in charge of the dog, which was fun." By the time she was a teen she was stage managing productions. She's an anthropology and art history major who came to Hopkins for the Program in Museums and Society. She produced Cabaret, attending just about every rehearsal and meeting of the entire production process. "It's a joke around Barnstormers that I've been doing this for a decade," she says.

This simple desire to do theater is what first drove students to create the company. When the Johns Hopkins University moved from downtown Baltimore to its Homewood campus in 1916, it didn't really have much in the way of student performing arts organizations. In early 1919, as reported in the Feb. 4, 1919, issue of The Johns Hopkins News-Letter, 12 students formed the Johns Hopkins Dramatic Club. For its first play, it chose George Bernard Shaw's You Never Can Tell, a comedy of errors about a mother and her three children returning to England after an extended stay abroad. Men were cast in all roles, including as women. It was directed by Clementine Walter, who the News-Letter notes "has studied for two years in Paris." It opened May 7, 1919, at the Albaugh's Theatre, which was located in midtown Baltimore.

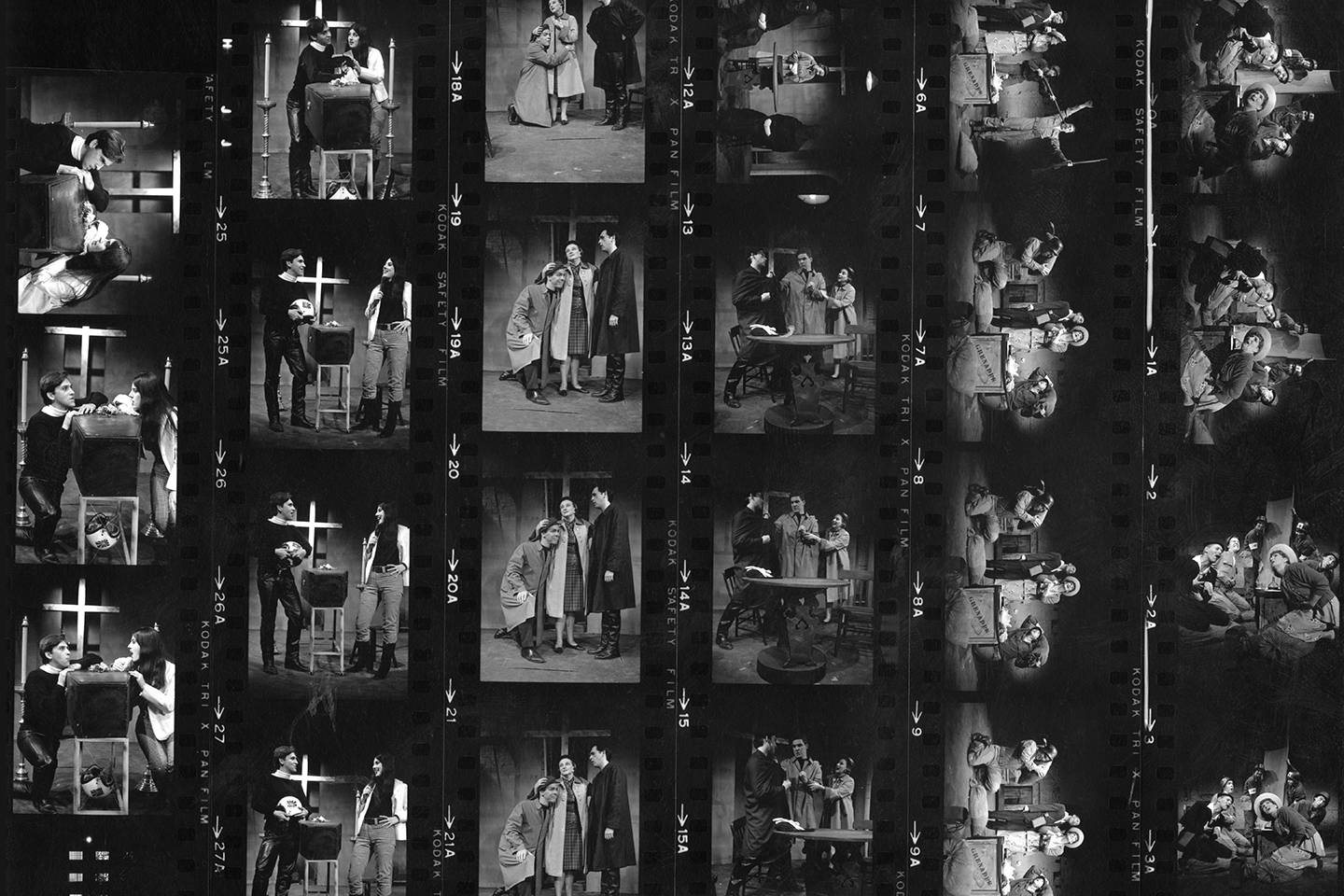

Image caption: Contact sheet from the Barnstormers' 1966 performance of Arrabal. Photographed by William C. Hamilton.

Image credit: Ferdinand Hamburger Archives, Sheridan Libraries, JHU

The Dramatic Club became the Barnstormers in 1924, taking its name from the barnstorming stunt pilots popular at the time. Casting women from other local colleges started in the '30s, and would last until Hopkins went co-ed in the 1970s. By the 1980s and '90s, Barnstormers settled into the production schedule it pretty much adheres to today—a freshman orientation show, Freshmen One-Acts, and a mainstage drama play during the fall semester; an intersession play; and a mainstage spring musical—and served as the crucible for other theater groups, such as the sketch comedy-oriented Throat Culture and student-written Witness Theater, that grew out of Barnstormers.

In recent years, Barnstormers have produced popular musicals such as Legally Blonde, Spring Awakening, and Pippin. "These are all shows that have had prominent Broadway, touring, and regional productions in the last 10 years," notes Cabaret director Hunter, a New York–based actor and director. He'd directed Cabaret before, and during his interview process with the Barnstormers executive board, they asked him what his take on it was, and he appreciated that they were looking for something slightly different.

For one, some men who've famously played Cabaret's emcee tend to be sexually fluid. Think Joel Grey from the original Broadway production and 1972 movie adaptation or Alan Cumming in the 1998 and 2014 Broadway revivals. Undergraduate Frank Guerriero, the Barnstormers emcee, looks like he could play point guard. "This emcee has more in common with American Psycho's Patrick Bateman and all the cliche?s and stereotypes that we identify with that kind of masculinity," Hunter says, adding that Barnstormers wanted to explore "what those tropes mean, what we can say about power, the state, and the darker energy the character embodies."

Image caption: Frank Guerriero's plays the emcee in Cabaret

Image credit: Frank Hamilton

Barnstormers didn't idly pick Cabaret. Hours, months, and sometimes years go into choosing their seasons. Members of the company can submit up to two plays or musicals for the following season, creating a long list of 20-25 titles. At an hours-long spring meeting of the entire company, those titles get whittled down to six options each for the fall play and spring musical. Over the summer, the executive board examines that list pragmatically: How much do rights cost? What's the size of the cast? What old props could be used or repurposed? Does the company have enough male singers for this show? If we did something serious this year should we do something light next year? And so on.

These are the same programming questions every theater company asks itself. Sometimes it takes a while for ideas to become realities. "I knew we were going to do Cabaret for the 100th-year anniversary two years ago," says producer Zimmerman, and follows it with a quick laugh. During her first two years with the company, she says, the company's ambitions grew as they realized they could do more with their work. They wanted to shift toward more socially aware theater that said something. In the spring of 2017, the company mounted Duncan Sheik and Steven Sater's Spring Awakening, a rock musical adaptation of Frank Wedekind's late-19th-century play about teenage sexuality. It's a frank exploration of adolescent sex and consent, and while #MeToo wouldn't become a social media hashtag until that fall, campus sexual abuse is something college students have dealt with for years.

"Part of what I like about being a producer is the ability to collaborate on a large scale in a bunch of different capacities to achieve this larger goal," Zimmerman says. "My job isn't to make the art, but I get to facilitate the making of art.

"I think part of what's exciting to all of us about theater is the way that how you present it can change what you gain from it," Zimmerman continues, adding that Spring Awakening "was the moment we shifted our priorities, not just because of the content of the material but the moment we were doing it."

Harmonized nonsense fills the Swirnow on a Monday night in late March. It sounds a bit like repetitions of zingy zingy zingy zingy progressing up and down a musical scale. Tonight's the first sing-through with the entire cast, and they're warming up their voices. Following the zingies, in unison they tackle the next vocal calisthenics, which sound like lidl ladl lidl ladl.

Hunter is joined by music director Matthew Dohm, whom the Barnstormers also hired for this production. Hunter fields a few questions from cast members about scene blocking and transitions while reminding everybody that tonight is more about setting the songs to muscle memory. Dohm has been working with the pit musicians. He sits at an electric piano to one side of the set and points out that the next time he joins the whole cast to rehearse, the entire pit will be there, too, so tonight is the only time they have to focus on the vocals.

Also: The show opens in 11 days.

In conversation, Hunter notes that he works with a number of student groups, and it's always interesting because the production processes are abbreviated. Barnstormers, however, "have a crazy preproduction and production mentality, which is fantastic," he says. "For them to hire just a director and musical director, it really puts pressure on the collaborative experience. They built the sets and designed the lights and are choreographing these numbers and are also doing the publicity. Coming from a background where I direct plays in New York and also fundraise, the weight of what they're doing to produce these shows is inspirational. They are wise beyond their years, they're tackling a giant show, producing it on their own. It's going to be great, and they're enjoying every second of it."

Every Barnstormer I spoke with discussed how much fun the organization is; built into that fun, though, is a practical education. Board members name check one or two mentors who took each of them under their wing when they were underclassmen. And this leadership training extends to working with the "adults" Barnstormers hires.

Novelist Kristopher Jansma, A&S '03, is currently an assistant professor of creative writing at SUNY New Paltz. He was Barnstormers president his senior year, and he recalls a conflict with the director they hired for one musical. A week before the opening, the director said he didn't like the poster and wanted his name removed, and then, the day before opening night, he wanted the set entirely repainted. "I can remember being this 20-year-old looking at this professional director and saying, 'No, that's not going to happen,'" Jansma says. "And he threw a fit and that was intimidating. But he had signed a contract, and too many people had worked way too hard to just chuck it out the window. Without Barnstormers, I think it might've taken me a few more years to realize that I could make decisions like that."

Part of collaboration is knowing when you have to stand up for yourself. Another part is accepting the expertise of somebody who knows more. At the sing-through, the cast recognizes they've got a way to go. For an hour, music director Dohm leads them through a handful of the first act's songs. "Money" requires extra attention, as it's a bit tricky. Its tempo changes a few times, speeding up at the very end. The lyrics have to move along faster than the rhythm that accompanies them. They're getting the song's timing down for the vocals, and they still have to add Albstein's choreography.

Dohm fine-tunes the song as they sing. He'll stop them, suggest a few things, and then try it again and again and again. They run through one section a few times, move onto the next section. Back and forth. That syllable should be on this beat, not that one.

After going through a few piecemeal sections, they sing it the whole way through. "OK," Dohm says, hands on hips. "We're very close to being better."

Edward Einhorn, A&S '92, recalls coming across a copy of Czech playwright and former President of Czechoslovakia Va?clav Havel's one-act Audience while a Hopkins undergrad. He caught the theater-directing bug as a first-year Barnstormer, directing Tom Stoppard's Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, and after graduating decided to mount Audience in New York, a do-it-yourself affair where he handled everything from producing and directing to set design and box office. After that, Einhorn would soon start his independent Untitled Theater Company No. 61, through which he would write and direct his own and experimental-leaning plays. He also ended up going to Prague, meeting Havel, organizing a celebrated Havel Festival in New York in 2006, and doing the first English translations of a few of Havel's plays. This year, his Untitled Theater Company No. 61 celebrates 25 years of producing intimate, challenging theater that's increasingly difficult to do in Broadway's blockbuster climate.

Barnstormers have gone into the professional entertainment world from its earliest days—former Barnstormer Thomas Beck, A&S '32, starred in 28 films in the 1930s, including Heidi opposite Shirley Temple—as both performers and back-of-house professionals.

"Hopkins really teaches you how to make theater out of nothing," says Ryan Whinnem, A&S '93, who adds that when he was an undergrad, Barnstormers staged productions in the converted lecture hall that is the Arellano Theater. In 1998, Whinnem and three fellow alumni—Bill Henry, Ruth Scrandis Henry, and Noel Schively—started Mobtown Players, a Baltimore-based company that initially staged Shakespeare and lasted about 12 years. He's founded three other companies since. "Barnstormers really taught me a little bit of everything—the writing, the directing, casting, set design—and the ability to work with what you've got. As long as there was a room that we could get electricity to, we could put on a show. And the ability to create theater out of nothing has served my theater career really well because it means you can do theater anywhere."

Barnstormers value this sink-or-swim theater education. Bill Henry, A&S '92, and a Baltimore city councilperson, recalls a classmate's description of Hopkins that's stuck with him over the years. "Most universities are like restaurants where you sit down and order something off the menu and they bring it to you," he says. "Hopkins is like a five-star restaurant with lots of expensive ingredients and great ambience, but you have to sneak into the kitchen and cook the food yourself. I think that's very accurate. You can do things at Hopkins that 99 percent of college students don't get to do, but you have to have the initiative.

"Hopkins' whole theater program was just us," he continues, adding that through working with Mobtown after graduating he worked with people who studied theater in college. "They have formal training in an artistic discipline that we didn't, but they were only then getting to make decisions for themselves that Barnstormers were making as 20-year-olds. There was an ownership over [our productions] that we didn't experience doing theater before. And for me it was great because there was no point in my life where my dream was to be a famous and successful actor."

Henry here is zeroing in on an elusive aspect that every Barnstormer I spoke with echoed in some way: Doing theater in and of itself provides something that other aspects of their lives and education don't. Sure, there's the camaraderie that others get through sports teams or Greek life. Yes, there's the professional skills that come with doing large projects on deadlines. And while few came out and said that nowhere else in their lives do they get to make art, it's the idea they all circled in some way.

One of the things producer Zimmerman likes about "Cabaret as a celebration of our anniversary is that it's a show about what it's like to live in a precarious time while doing entertainment," she says. "I don't want to say [Cabaret] is about using entertainment to process what's happening, but I think it does a really good job of saying you can't ignore what's going on, we need to face the world and deal with it. I think that's an important message now and a good message for our anniversary, that you can't live in the flash and glitz of everything."

If you've never seen Cabaret, its first act ends by revealing that one lovable character is a member of the Nazi Party. It's shocking, deflating its playfulness. The second act unfolds under a dark cloud, and Barnstormers poignantly stages its sobering final tableau as a visual echo to the Shoes on the Danube Bank memorial in Budapest that honors the Jews killed by Hungary's fascist party in World War II. Even if you don't recognize the allusion, the musical's final image is effectively unsettling.

Without being didactic or obvious, Barnstormers' Cabaret entertainingly created a world where people are having to make hard decisions about their own future and the future of their countrymen's lives. Yes, it was a student production with a modest budget, but on opening night when the lights went down on that final image, a chilling silence swallowed the theater before the lights came back. Cue applause.

"Hopkins is pretty socially unforgiving," says technical director Laura Nugent, A&S '19, and names a couple of pressures familiar to every Hopkins undergrad: the massive workload, the personal expectations. She learned lighting design during her four Barnstormers years, and she sits through rehearsals to understand what's narratively and emotionally going on. "Part of my job is to ask, What color is this song?" she says. "It seems like there shouldn't be a right answer, but there is."

The week leading up to opening night, tech week, is also called hell week for a reason. All of the costumes, makeup, props, and lighting choices get added to the production in one long test of sanity and endurance. For the lighting designer, it's a puzzle of moving and focusing lights for each song/scene, finding the right color gels for setups, and marking cues for turning them on and off. "By opening night, I've seen the show a million times," Nugent continues. "And when the lights first come up, I sneak a look at the faces of people in the crowd. And they're like, 'I can't believe a bunch of kids pulled this off.' And to have something where you can go through all the pressure of rehearsals and tech week with your friends and you immediately get that, it's incredibly satisfying."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Student Life

Tagged theater, barnstormers