Last fall, Johns Hopkins senior Juliann Susas sat in Gilman Hall on the first day of her History of Law and Social Justice course as the professor, historian Martha S. Jones, walked everyone through the syllabus. Susas is an international studies and history major, and she had registered for the course because she hopes to practice law one day. She expected a semester of heavy reading, rigorous debate, and long research papers, so when Jones got to the part about Twitter representing 30 percent of a student's grade, Susas took notice.

Jones explained to her 20-plus students that in lieu of traditional exams, they would log on to Twitter for six hourlong sessions throughout the semester and would use the social media platform to answer questions posed by her about their shared readings. The students would each have to respond to the professor's questions by distilling their answers to 280 characters—the current limit for one tweet—or learn to "thread" their responses together for a longer answer. Jones would grade them on the basis of their replies. The sessions, organized under the hashtag #lawsocialjustice, would also be open to the general public, meaning students might have to engage with people outside of class interested in debating, say, the legacy of Brown v. Board of Education.

At the time, Susas, age 21, was not a heavy Twitter user. She'd first logged on in high school but had only sporadically returned to the site to follow her favorite television shows and entertainment news. "I think this is my bias coming from a younger generation, but I thought Twitter was only being used by people my age, or by people trying to market to people my age," Susas says.

Jones, who has over 12,000 followers, sees Twitter differently. A former lawyer turned 19th-century U.S. historian, Jones focuses on law, race, culture, and inequality. She is a self-professed "archive rat" who has long shared her research through traditional academic journals and books, but Twitter, she says, has emerged as another tool in the scholar's quest for information and idea dissemination.

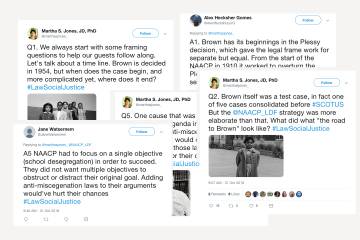

Q1. We always start with some framing questions to help our guests follow along. Let's talk about a time line. Brown is decided in 1954, but when does the case begin, and more complicated yet, where does it end? #LawSocialJustice pic.twitter.com/9k5qWJte79

— Martha S. Jones, JD, PhD (@marthasjones_) October 31, 2018

"There's a robust community of archivists, museum curators, historians, social studies teachers, and American government experts who are active on the site, and there is a great deal of learning and teaching going on there," Jones says. (Some historians on Twitter have taken to communicating with one another using the hashtag #Twitterstorian.) Jones says that on any given day, one can easily wind up talking with a Pulitzer Prize winner or a National Book Award winner about a topic of interest. Jones hoped to expose her students to this other side of Twitter and get them thinking of the site as another way to build historical knowledge.

"Many students go onto these sites naively—the cost of the ticket is nothing except opening an account—and my goal has been to help them appreciate what there is to learn on Twitter," Jones says. She also teaches them how to block out the background noise that exists on a largely unfiltered platform where cat pictures and presidential pronouncements coexist.

She explained to her students how academics routinely share new research on Twitter, and how she uses the site as a way to inform conversations and connect with people for the exchange of new ideas and analysis. On Twitter, scholars are effectively creating open and public scholarship. All of this surprised Susas. "I didn't know any of that existed," she says.

The platform has also proved indispensable in bringing Jones' writing and research to a global audience. Last year, after Jones tweeted about subject matter from her latest book, Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America, a reporter reached out about an article featuring Jones' research. "The writer encountered my book on Twitter and that's how a story in The New York Times came about," Jones says.

Thank you Martha. I love the #LawSocialJustice chats. The chats are fabulous open discussions for all to participate in and learn from; the cases, your questions and the @JohnsHopkins' students thoughtful responses are all terrific. Looking forward to the next time around!

— Shawn Leigh Alexander (@S_L_Alexander) December 5, 2018

Jones certainly isn't the only academic taking advantage of the global network. As of 2010, just four years after Twitter launched, as many as 40 percent of academics were creating accounts, and since then, scholars have harnessed the site as a way to disseminate ideas beyond the traditional Ivory Tower peer-reviewed journals, both to raise their stature and to be regarded as publicly engaged scholars. By 2016, the American Sociological Association even suggested in a report that schools might consider whether social media activity could count toward tenure or promotion, an idea that Patrick Iber, an assistant professor of history at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, wrote at the time "conjures a special sort of dread" in some. "You can, of course, be a publicly engaged scholar in many ways, but the anxieties about Twitter seem particularly acute," he wrote in an article for the website Inside Higher Ed. "It is sometimes reviled as a waste of time to be avoided. But it is most often treated with puzzlement."

And no wonder. Twitter can often feel like it toggles between a dumping ground for insipid memes and a troll-fed dumpster fire where people scream into the virtual ether, leaving some scholars to question whether it's a worthy investment in an already overscheduled career. In a 2016 New York Times op-ed, Cal Newport, an associate professor of computer science at Georgetown University and the author of the book Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World, argued that if you're serious about scholarship, you should stay offline. "These networks are fun, but you're deluding yourself if you think that Twitter messages, posts, and 'likes' are a productive use of your time," Newport wrote.

And yet, a subset of Twitter users is harnessing the platform for pedagogy and public engagement. Here, traditional classroom instruction meets crowdsourcing and collaboration among students, professors, and experts in myriad fields. Academics, including many at Johns Hopkins, are turning to Twitter not only for teaching their students but also for their own professional development, advocacy, and networking. Economist Steve Hanke, a professor of applied economics at Hopkins, uses the site to bring his fast-paced market research to the masses, and he credits his Twitter account with raising his profile globally. "Joining Twitter turned out to be one of the most fantastic things I've ever done," says Hanke, who is now ranked as the 13th most widely followed economist on the site, and who is followed by government officials from Venezuela to Turkey.

Twitter has become an important element in some academic portfolios, but it is also heavily debated. One recent headline in The Atlantic, "To Tweet or Not to Tweet?", sums up the latest flurry of blog posts, articles, and op-eds on the topic. Should academics take to Twitter? And should they encourage students to do the same? In talking with seasoned Twitter users across the Johns Hopkins community, there is consensus that creating a deliberate, professional digital identity can support both scholarly work and student achievement. But it comes with pitfalls. The trick to success in the Twittersphere, they say, is in learning how to use it without falling prey to trolls, wasted time, and misfired ideas.

In 2014, when Michael Brown, an African-American teenager, was fatally shot by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, the subsequent uprising created a state of emergency in that city as well as a national outcry over entrenched racism and inequity in America. Marcia Chatelain, an associate professor of history and African-American studies at Georgetown University, created the hashtag #FergusonSyllabus as a way to supply teachers and parents with resources to help children understand the complexities of such a traumatic event. Soon, the hashtag was being used to connect people to essays, articles, and eyewitness testimonies that centered on history, race, and politics. This is when Jones, who had joined Twitter in 2012, really saw the potential of the site. "There was a coming together of scholars and activists and journalists who were very much ahead of the mainstream news outlets in not only covering events in Ferguson but also in providing insightful commentary," Jones says. "It turned out to be an important place to have conversations that had no equivalent elsewhere in the media."

The following year, Dylann Roof murdered nine African-Americans during a prayer meeting inside Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina, and the dearth of nuanced, timely discussions about race and white supremacy in the public sphere prompted dialogue under the hashtag #CharlestonSyllabus. Within an hour of the hashtag appearing, it was trending on Twitter.

"Social media has become a vital tool for communal learning and the spread of knowledge beyond traditional sources," wrote the editors of the book Charleston Syllabus: Readings on Race, Racism, and Racial Violence. "Twitter, in particular, has emerged as an important democratic space for challenging mainstream media narratives and engaging critical dialogue." A thoughtful use of hashtags, the editors wrote, can "serve as a bibliographic marker and tool for historical literacy."

Jessica Marie Johnson, an assistant professor in the Department of History at Johns Hopkins, is a historian of Atlantic slavery and the Atlantic African diaspora, but she is also a digital humanist who studies the ways in which social media creates and disseminates ideas. When Johnson joined Twitter in 2009, she already had a robust online presence participating in black and queer digital communities. At first, she saw Twitter as a way to connect with a community of people interested in social justice, but slowly she realized the site was also a place where she could interact with people conducting research similar to hers. Her interest in the site grew as she watched marginalized communities and people of color co-opt the space to organize around social justice issues, such as the fact that trans people of color have some of the highest death rates in the country. "Platforms like Twitter weren't created with people of African descent in mind, and yet black digital [communities] have proactively used them," Johnson says. "In the beginning, I didn't think that I was going to be on Twitter much, but there's exposure to new ideas and people doing interesting work that I may never have seen otherwise and that really is amazing."

Today, Johnson's Twitter account has over 12,000 followers, and she built that platform by creating a deliberate persona online. "When I first started this account, I wanted to be professional, and I wanted to be able to speak publicly, intelligently, and with emotion about what was happening to black people in the world," she says. "Within a year, I also realized that I didn't want to feel like I was on Twitter as a stuffy historian."

Johnson now describes her online personality as "70 percent history/scholarship/slavery studies, and 30 percent trash." Meaning you may get a tweet about her latest research followed by one about twerking or the singer/rapper Cardi B. "I embody that persona and it reflects my politics and who I am," she says.

Johnson says that every Twitter user—especially students—needs to step back and ask: What am I doing here?

"If you want to use this as a scholarly place only, don't tweet about your lunch today," she says. "If you want to connect only with family and friends, then make your account private."

Also see

How to present oneself on Twitter was one of the first lessons that Jones taught her students in her History of Law and Social Justice course.

"Some young people are conducting their lives in these spaces without thought about how they are perceived. And as university students, it's important for them to think about this as a professional and public space where they might encounter employers or peers," Jones says.

For her class, Jones invited Elizabeth Voss, social media manager for the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, to talk about how best to form a Twitter presence. Voss' day job includes making sure that social media channels support the more than 50 departments, programs, centers, and institutes within or affiliated with the Krieger School of Arts & Sciences.

Voss wondered, though, what "a middle-aged woman like me could teach these kids who grew up online," and she was surprised to learn that for many of Jones' students, this was their first experience using Twitter. They use sites like Instagram much more, Voss says. "One of their main goals, they told me, was to just get comfortable using Twitter." So, Voss shared her process for developing an online strategy.

"The weird thing about Twitter is that it walks the line between professional and personal," she says. "You can have a professional presence, but it's also you on there. So, before you dive in and start tweeting, you should have clear goals." For example, determine the audience you hope to reach. In the case of Jones' class, the students would engage not only with their classmates and professor, but they might also encounter experts in the subject matter and anyone interested in learning more about the topics they were discussing.

Susas decided to create a new Twitter handle because she felt like her existing one—where she followed mostly entertainment news—wasn't appropriate. The first time she logged on for a Twitter session for class, Susas found it overwhelming. Jones sent rapid-fire questions labeled Q1, Q2. When Jones tweeted: Q1. The Amistad case is one that plays out for African captives on the west coast of Africa, across the Middle Passage, and in the waters off of Cuba. How does it come to be examined before US courts? #lawsocialjustice, the students had to quickly answer by replying to her tweet. Soon historians and others from around the country chimed in as well.

Jones encouraged these outside commenters by advertising the discussions on Twitter in advance and asking people to follow the hashtag.

BTW, even as the semester is wrapped up, I love how our #LawSocialJustice chats continue to resonate here. Thanks, friends. https://t.co/6WarD4JS0N

— Martha S. Jones, JD, PhD (@marthasjones_) December 19, 2018

"I wanted the students to test their understanding of their course material in front of a live audience," Jones says, "because I also wanted them to realize that they can be the teachers and producers of knowledge online. There are people [on Twitter] who want to learn what's happening in our studies and research at Hopkins."

Susas says the first sessions were stressful. "You had to know your material really well, answer all these questions, respond to your peers, and keep up with Professor Jones, as well as new people from outside class responding to our tweets." Soon though, Susas came to enjoy the fast-paced discussions. She found that the exercise helped her coalesce her thoughts about the subject matter more concisely. "It never felt like an hour," she says.

In some instances, it's the student who leads the professor to Twitter. In 2012, Wyatt Larkin, A&S '13, then a rising senior at Johns Hopkins, was a student of Steve Hanke. Hanke, an applied economist who served on President Reagan's Council of Economic Advisers, was regularly publishing op-eds in magazines and newspapers and articles in academic journals about his research into troubled currencies. But few media outlets were reporting his data. "In the summer and fall of 2012 there was a crisis in Iran with the currency, and at the time Professor Hanke had the data on the true exchange rate of that currency. As a result, he was the only economist who could accurately calculate Iran's inflation rate," Larkin says. "He was getting frustrated because he had this data and he was trying to get reporters to understand that the crisis was much worse than was being reported, but he wasn't reaching anyone."

One day, Larkin approached his professor and suggested that Hanke open a Twitter account to spread the word about his research programs, including his Troubled Currency Project, which collects black market exchange-rate data for unstable currencies. Hanke chuckles now as he recalls his response. "I said to Wyatt, 'What's Twitter?' I had no idea."

Larkin created a new account on Hanke's behalf and wrote tweets with his professor's input. "Whenever a magazine or newspaper would post an article about Iran, we'd tweet at them and say, 'This is the wrong data, here's what you need to know,' and very quickly, Hanke's research got in front of writers for The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and the BBC, among others," says Larkin, who is now the digital media director and speech writer for Sen. Mark Warner, a Democrat from Virginia.

Hyperinflation's crushing effects on display in #Venezuela https://t.co/H2ozithpPF

— Prof. Steve Hanke (@steve_hanke) March 11, 2019

Larkin and fellow students also used Twitter to support research on troubled currencies. "We figured out the hashtag that black market currency dealers were using to report the rate in Iran and that was how we were figuring out the exchange rate," Larkin says. (Other researchers at Hopkins have mined Twitter for data over the years, including a 2013 project by Mark Dredze, an associate professor in the Department of Computer Science, that mapped the spread of the flu virus by following global Twitter activity.)

Twitter started as a lark, Hanke says, but he quickly saw its value for his students, not just for research but also for sharpening their rhetorical skills. Learning to distill ideas into 280 characters requires a mastery of understanding.

"Writing well is a display of how well you're thinking," Hanke says. "Twitter is complementing what I've always been doing, which is teaching students how to write. A successful tweet can't have two or three different ideas. It has to be clear, concise, and communicate one idea."

Susas also learned this lesson last fall in Jones' class. "I am used to writing academic papers, and this was very different," she says. "With papers, they can be long-winded, but in a tweet you have to say it succinctly. You had to say everything you wanted in a sentence or two. I found myself cutting out adjectives. It helped me learn to get to the point, even in my daily life."

Hanke has maintained an active Twitter account ever since 2012, posting daily and keeping his online presence scholarly and professional. Today, he has over 116,000 followers.

Gaining such a large following is a goal for many Twitter users—the larger your platform, the larger your influence—but size also affects how you tweet, according to Roger Peng, a professor in the Department of Biostatistics at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Peng first joined Twitter in 2007, and at first "he didn't get it," he says. "The platform was evolving and [users were] figuring out what it was for. I felt like back then it was mostly random notes like, 'Hey! I'm eating a sandwich!'"

Peng kept it casual at first, tweeting with friends and colleagues and saying whatever came to mind, but as Twitter matured, and as people began to use it more, something clicked for him. He professionalized his account and grew his following, all while investing time in networking and following other people in his field. Today, Peng's account has nearly 35,000 followers, and he says there's an added responsibility with that increase. "I'm much more cautious about what I tweet now that tens of thousands of followers see it," he says. "My approach to Twitter is more akin to press releases. I'll link to a new blog post that I wrote, or a new podcast that I created. In the past, I had more random spoutings, and I've gotten rid of those. I've tried to professionalize the feed."

Posting to Twitter, he says, does make a difference in that it drives people to his other projects. "If I send a tweet about a book I've written, it does make a difference in sales of that book," Peng says.

Still, there are days when Peng wonders if it's worth it. "Some people get a lot out of Twitter, and some people are wasting their time, and part of the challenge is figuring out how it can be relevant to you in a reasonable amount of time," he says. "I've swung back and forth about it being useful, honestly."

And while the site may be invaluable for getting scholarship and research out to a broader audience, it can open up a Pandora's box.

One afternoon, Johns Hopkins planetary scientist Sarah Hörst entered a vault in Texas where rare meteorites and other planetary matter are stored. "I was in there with the curator and she's pulling out drawers and she hands me a rock, and it's a piece of Mars. And then she hands me a piece of the moon. I asked her if I could take a picture and post it on Twitter." The caption read, "This is what my face looks like when someone lets me hold a piece of the moon and Mars at the same time."

This is what my face looks like when someone lets me hold a piece of the Moon and Mars at the same time pic.twitter.com/wMN1HhXKpW

— Dr./Prof. Sarah Hörst (@PlanetDr) April 13, 2018

Hörst went to dinner that night with colleagues and when she pulled out her phone later, the tweet had "totally blown up," she says. With over 87,000 likes it became a Twitter Moment. Soon the rocks had their own account, created by a fellow scientist. "It wasn't a purposeful attempt to get a lot of reaction, it was just me sharing science as I always do," she says.

Hörst, who has nearly 50,000 followers, has been named one of the top women in space studies to follow on Twitter by Silicone Republic, a website for professionals working in science and technology, in part because she gives her followers an often witty behind-the-scenes look at her research into the complex organic chemistry of planetary atmospheres. But when she tweets about gender, sexism, or racism in science, the backlash can be swift. "If you're a woman on the internet you have to expect that you're going to get a lot of pushback," Hörst says. "Saying things that are critical can very rapidly result in you getting a lot of negative pushback, which is not something I had anticipated until I found myself in it. It's not surprising but still disappointing."

In December 2018, Amnesty International released the results of a new study that confirmed what many already suspected: Women, particularly women of color and those in professional fields, get harassed on Twitter far more frequently than others. Hörst, for instance, tweeted about SpaceX, Elon Musk's privatized space exploration project, and discovered that the "bros" of space exploration were ready to strike.

"I have a lot of followers and things can escalate quickly," Hörst says. "I've learned over the years that the easiest thing to do is just to lock my account for a bit so that the only people who can see my tweets are people who already follow me and no one can retweet me."

It can be overwhelming when a tweet goes viral, and managing the aftermath can be difficult. In May of 2018, when it was revealed that families were being separated at the U.S. border, Jones joined the swift and impassioned backlash on Twitter. "I posted a series of tweets about how, in the 19th century, children were separated from parents through the institution of slavery," she says. Several of her tweets went viral "as in the millions," Jones says, and suddenly people wanted to talk. "I had struck a very emotional chord, and I wasn't in any way prepared to be a sounding board or a caretaker with hundreds of thousands of people. Every reaction was coming into my feed and I felt moved by that, but also obligated, particularly for people who had questions and needed more information."

Forcibly separating parents from children has a history; it is our history. pic.twitter.com/1OgxeCLF8V

— Martha S. Jones, JD, PhD (@marthasjones_) May 26, 2018

On the advice of a mentor, Jones stepped away from her own work for a few days in order to respond to the Twitter outcry. "It was heavy," she says. "This was far beyond the universe of my students or my followers. There were people all over the globe reaching out."

And some of the commenters were ready to fight. "I'm interested in having an influence on the quality of what happens on Twitter. When people are out of bounds on my timeline, I can say: This doesn't work for me." Jones says she imagines it a bit like inviting someone onto her porch. "I can say: sit down. Have a cup of tea. Let's talk about hard questions. But if you're not here to do that, you should keep walking."

Like Peng, there are days when Jones considers leaving the site. Hörst, too. But Jones believes avoiding social media altogether isn't the answer. "Some people who disparage social media and refuse to now use it are the same ones who swore they'd never use email," Jones says, "and yet isn't it our obligation to orient our students to these spaces, to familiarize them to what's possible and what the dangers might be? I want people to understand it, even people who are not going to ultimately use it themselves."

Now that class is over, Susas has decided to keep her Twitter account active. She'll continue to seek out scholarly conversations, as she did in Jones' class, and keep it professional. "It was eye-opening to see how people outside of college campuses are talking about these same topics that we're studying in the classroom," Susas says. "The experience reminded me that the stuff I'm learning in the humanities, it has relevance in the real world."

Posted in Science+Technology, Politics+Society

Tagged social media, twitter