A migration was transpiring in American living rooms in 1948. Families that had once gathered around one box—the radio—now coalesced around a new cubical intrusion: the television set. These were TV's early days to be sure. Only about two dozen television stations were operating in the country, broadcasting to perhaps as few as 250,000 sets. Coast-to-coast networks didn't exist.

Still, some storied names made their small-screen debut that year, including Ed Sullivan and Milton Berle. The latter, an erstwhile vaudevillian, would be crowned "Mr. Television" as host of the hugely popular Texaco Star Theater variety show. The program became a Tuesday evening staple. Before Uncle Miltie, as he was known, hit the stage—probably in some laugh-inducing, silly getup—a quartet of uniformed service station attendants sang the theme song: "Our show tonight is powerful, we'll wow you with an hour-full, of howls from a shower-full of stars."

But some folks basking in the glow of their brand-new Philcos or Admirals on a Tuesday night tuned in to an altogether different kind of program with its own dramatic intro: a theatrical kettle drum roll, a barrage of stern orchestral music, and a camera panning across Gilman Hall and its iconic clock tower. Then, the title sequence: The Johns Hopkins Science Review.

Video credit: Sheridan Libraries / Dave Schmelick

"This is Johns Hopkins University," an announcer says with crisp, newsreel intonation. "Here, in its many laboratories, Hopkins scientists are constantly probing the still-unknown secrets of science which, when discovered, will be translated into benefits to be enjoyed by you, the people of America."

Viewers were then promised an "over the shoulders" glimpse of such research. The debut episode was "All About the Atom" and featured eminent physicist and atomic energy pioneer Franco Rasetti. And so began the university's dozen-year adventure in television, with episodes covering topics from archaeology to zoology, with a who's who of notable guests from the university's schools and beyond, such as pioneering German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun and big bang theorist George Gamow. The show changed networks and names over the years but, taken as a whole, is one of the longest-running programs in the first golden age of television.

Just over 300 of the more than 500 episodes that aired have survived. They are archived at the Milton S. Eisenhower Library's Special Collections department, and some are viewable online. Not a bad figure, as these things go, since video recording equipment wasn't developed and put into wide use until the mid-1950s and many live shows of the era simply disappeared as soon as they were broadcast. The Hopkins programs survived via kinescoping, a fancy term for pointing a 16-mm movie camera at a TV monitor. Queue up these early programs, and contrasted against our high-def, CGI razzle-dazzle era, the fuzzy black-and-white show seems decidedly frumpy. Sets and props made of plywood and papier-ma?che?. The flubbed lines and awkward pauses of nontelegenic scientists working live. The ashtrays! And there are times you'll want to reach through the screen with a comb to tame some learned professor's pesky cowlick. But don't simply dismiss them as campy time capsules from the Kukla, Fran and Ollie era when ad-libbing puppets delighted audiences.

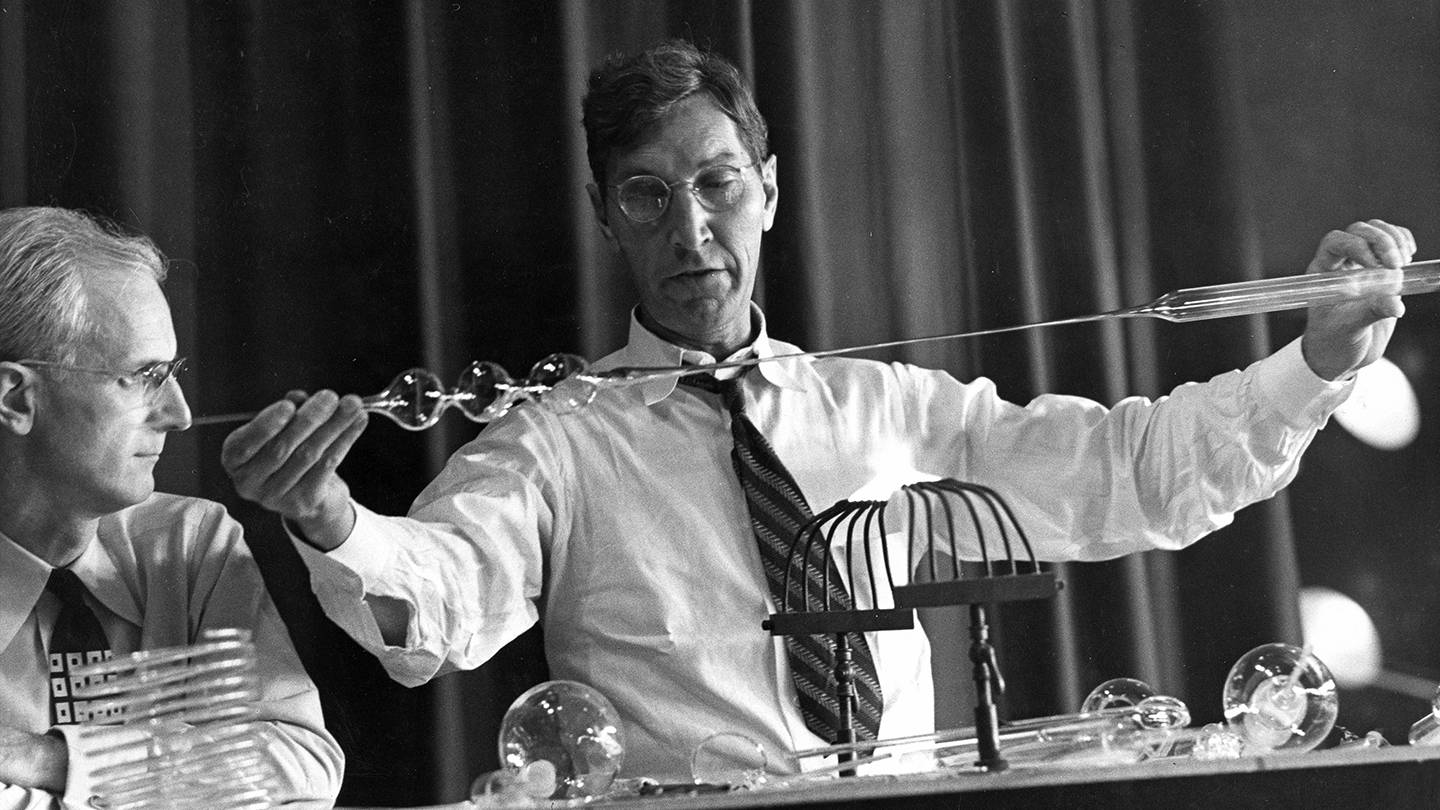

Image caption: Poole looks on as master glass blower John Lehman holds his work-in-progress over a flame of gas jets.

Image credit: Sheridan Libraries / Johns Hopkins University

The Science Review won a pair of George Peabody Awards for programming excellence and merited barrels of good ink. The New Yorker called it "tremendously impressive," and the Chicago Tribune wrote: "This is an educational show, just about the best on the air." And it took on taboos. In a pearl-clutching age when a very pregnant Lucille Ball was forbidden to utter the word "pregnant" on her namesake sitcom (in which the marital boudoir featured twin beds), the Review showed a snippet of a live birth and, when covering cervical cancer, had School of Medicine gynecology Professor Richard TeLinde discuss the uterus and vagina while holding a speculum.

"It was path-making in a number of ways," says historian Marcel Chotkowski LaFollette, author of Science on the Air: Popularizers and Personalities on Radio and Early Television and Science on American Television: A History. "One, it was successful—it went on the air and then stayed on the air. It showed the scientific community that science could seriously and accurately be presented on television, which most scientists regarded as a frivolous medium. And it also really paved the way for a lot of science demonstrations on television, which get people interested and we now take for granted."

In its prime-time years, this cerebral show dwelt in the ratings shadows of far fluffier fare, not only going up against Milton Berle but later Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts—the American Idol of its day—and the cop-drama Dragnet. Today, as Science Review episodes slip onto YouTube and even Amazon Prime, the groundbreaking series can be widely seen for the first time in more than 50 years.

But is there a direct link between this dowdy, black-and-white program and the slick, sophisticated science shows of the modern television era—Cosmos, Nova, Bill Nye the Science Guy? Not exactly, says Ingrid Ockert, who studied the Hopkins science TV shows for her doctoral dissertation at Princeton University last year. "It was on at the wrong time—before the craze with science education really took off after Sputnik—and on a channel that nobody remembers," she says. "But it's not its influence that's amazing so much as that they made it at all. And that it survives."

The university's foray into the fledgling world of science television is largely owing to the efforts of a singular (and decidedly nonscientific) individual named Lynn Poole. In many respects, he carried the program on his suit's padded shoulders. Poole, the university's first director of public relations, was the show's creator and host, and more often than not, its producer, writer, and roustabout. Call him Mr. Science Television.

Poole earned AB and MA degrees from Case Western Reserve University, where he studied art history, education, and aesthetics. He painted, spoke fluent Greek, and was a founding member of the American Society for Aesthetics. He even performed for a time as an interpretive dancer. Promotional materials from his dance days show him stripped to the waist in flowing harem pants, a far cry from the trim suits and perfect pocket squares of his bespectacled TV persona.

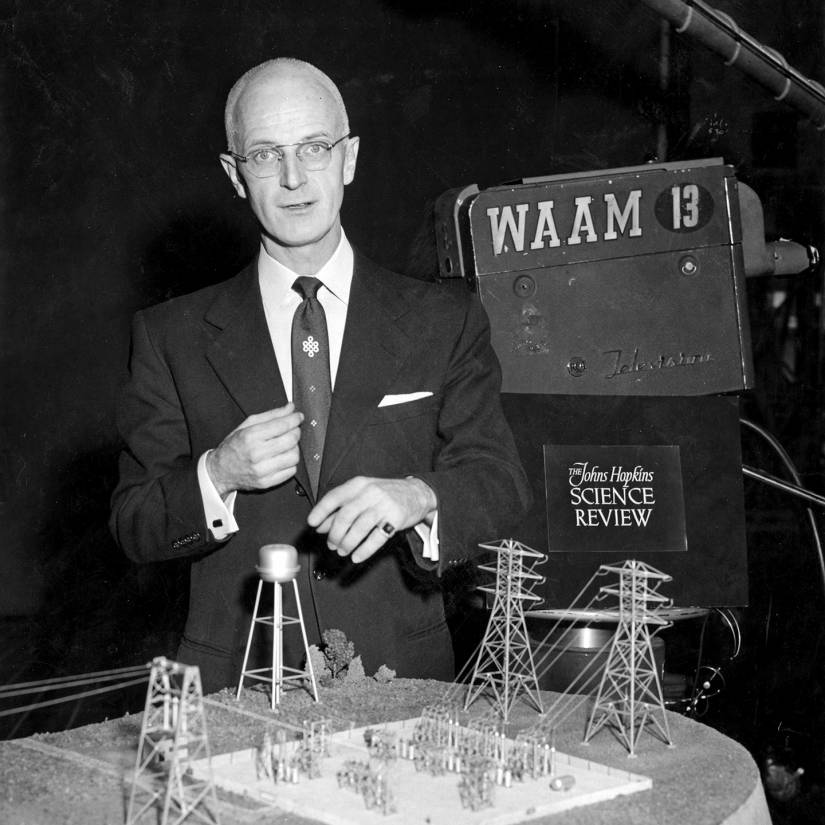

Image caption: Poole stands over an architectural model of water towers and telephone lines during the filming of “The Peaceful Atom, Part 1.”

Image credit: Sheridan Libraries / Johns Hopkins University

Poole, who was born in Iowa, came to Baltimore in 1938 to launch the education department at the Walters Art Museum. During World War II, he served as a public relations officer in the Air Corps, where he sometimes accompanied flight crews on bombing missions and put together the traveling show Wings Over America. He was discharged from the military a major and arrived at Hopkins in 1946 enamored of television's potential. "When radio was a raucous infant, ivory-towered educators scoffed at it," he wrote in the journal College Public Relations in January 1949. "Today, we are in the same position with television ... as public relations directors, we must examine this new medium and be ready to become an integral part of it."

When Baltimore's first station—WMAR-TV—opened its doors in 1947, it solicited the Baltimore community for programming ideas. Poole pounced on the opportunity. "We walked into the studios along with the cameraman and learned it from the ground up, along with the directors and others who didn't know any more about television than we did," Poole told The Baltimore Sun in 1958.

Each half-hour Science Review was built around a theme and featured discussions and demonstrations by one or more guest scientists, doctors, or engineers from Johns Hopkins and other universities or laboratories. Many of those early episodes are lost to the ether, so we can't see for ourselves how "Plastic—The Modern Miracle," "X-ray: How It Works for You," or "Search for a Perfect Insect Repellent" played out. We do know the episode "The World From 70 Miles Up," which aired in December 1948 and gave Americans their loftiest view of the world yet, as a primitive rocket carrying cameras blasted off into the stratosphere.

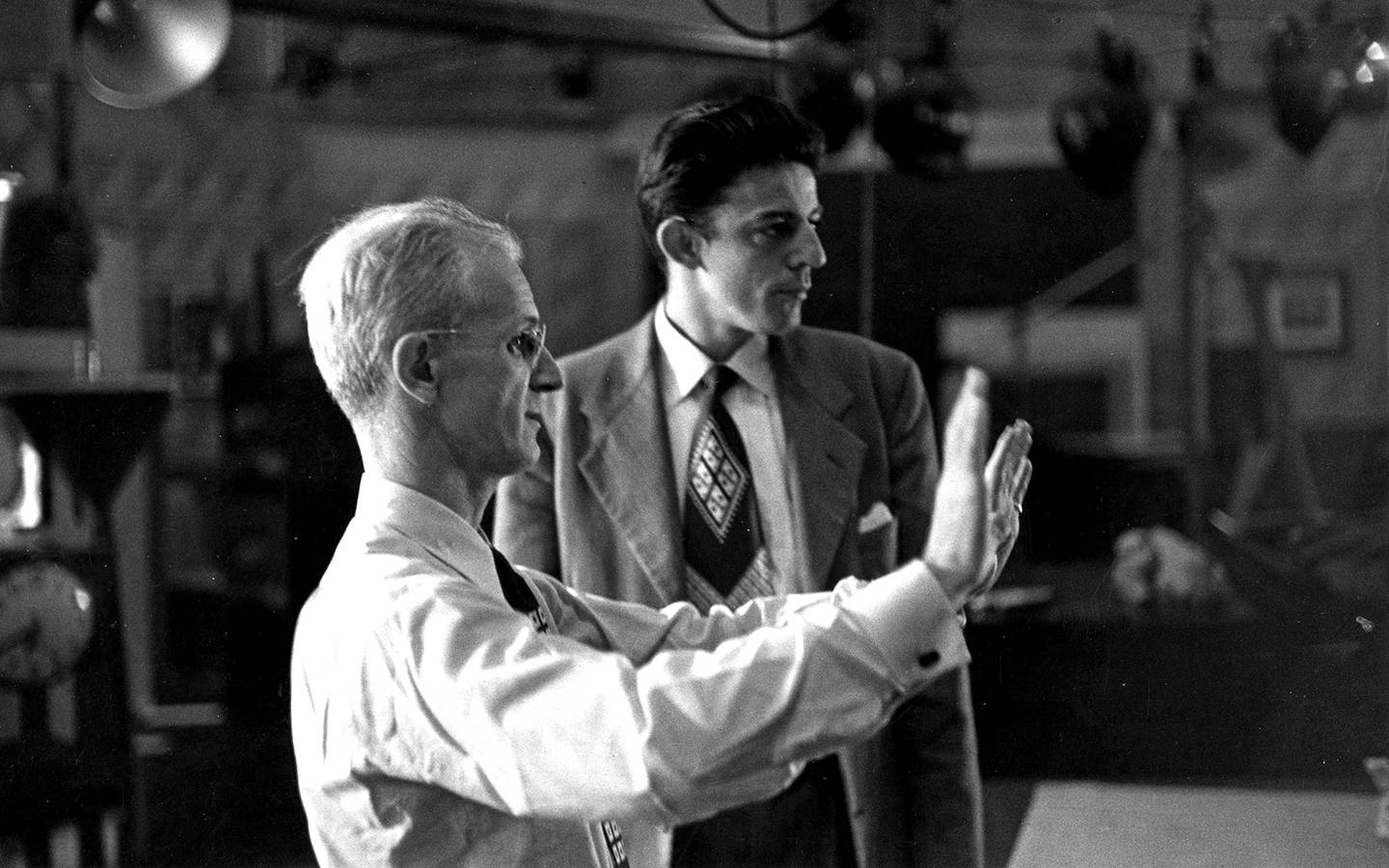

Image caption: Poole talks with John Astin, then a student actor, about where to stand in the opening scene.

Image credit: Sheridan Libraries / Johns Hopkins University

Poole hadn't intended to be the onscreen host. The story goes that very early on, one nervous guest scientist refused to go in front of the camera alone. Poole joined him under the lights, and his cool, urbane persona was a calming on-screen presence. Slight of build and with close-cropped white hair that retreated backward a little more each season, Poole might not have fit the idealized mold of dashing television host, but the former dancer was at ease with the pressures of live performance. He forgot a guest's name on air once but never broke stride. He turned it into a self-deprecating joke.

At first the program aired only in Baltimore, but in the fall of 1948, it was picked up by CBS, which had a fledgling four-city network: Washington, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York. In 1949, the program moved to Baltimore's WAAM, and when that station joined the DuMont network the following year, the Review was on its way to being broadcast to upward of 200 cities.

How many people were actually watching is another matter, as it barely registered in the era's early rating systems. While Berle was a ratings juggernaut and I Love Lucy was known to draw more than 40 million viewers, it was estimated that fewer than 500,000 folks tuned in to the Review. "You have to be kind when looking back," LaFollette says. "Today, we look at things such as how many millions of Twitter followers you have. But in those days, if you had even 50,000, or 100,000 viewers across the country, and it's influencing thousands of people who are absorbing what's going on, it matters." The show received a thicket of fan mail each week, including multiple letters from viewers telling how the show's frank information about cancer symptoms and examinations had saved a loved one's life.

All this from a penny-pinching program that probably spent less money on a whole season's worth of content than the celebrity shows consumed in a single episode. Warren Wightman, a Review co-producer and writer in its early days, recalled the lean years in some written reminiscences in 2008. "We had to improvise for everything because we didn't have a production budget," he wrote. "[Poole] said we could spend $300 at the most on a show, but not on every show. It came out of petty cash, I think. Most of the time we didn't even spend that." For a three-part series called "Man Will Conquer Space," show staff constructed a 16-foot-tall plywood rocket to use in the intro. A certain famed rocketeer appearing on that program was unimpressed. "Von Braun looked down his nose at our amateurish efforts and wanted to leave the rocket bit out, but [Poole] ignored his protests," Wightman recalled.

View this post on Instagram

The 1952 episode "A Visit to Our Studio" gave viewers a behind-the-scenes peek at the WAAM facilities where the show was shot. What was state-of-the-art at the time seems so labor-intensive now—the unwieldy cameras on huge dollies, the music queued up on giant shellac discs. The set in this era was little more than a standard-issue wooden desk with some bookshelves behind it. Guest scientists were provided with a table or blackboard off to the side.

The Saturday Evening Post writer Robert Yoder summed up the Review's situation in a 1954 article titled "TV's Shoestring Surprise." While Berle was reportedly earning $200,000 a year to do his show, Poole is depicted hustling up borrowed props in a borrowed truck. Yoder wrote: "In their constant battle to get along without money, Poole and his assistants have become the most talented borrowers on the Eastern Seaboard. They will borrow your grandfather's picture off the living room wall, a hair dryer from a beauty parlor, a uniform from a policeman."

Poole took on the role of hustler because he was sure he was onto something. Barely two years into the role of science broadcaster, he wrote Science via Television, a how-to guidebook replete with both nuts-and-bolts studio advice and his guiding philosophy: "An educational program can be entertaining, have a fast pace, and employ any number of 'gimmicks'—but it should always stay within the realm of dignity," he wrote. "A science program is not a vaudeville show." That said, Poole also understood television entertainment. He once ate a grasshopper on camera for a show about insects; for one on fear, he had a king snake—on loan from the Maryland Zoo in Baltimore—tossed into an unsuspecting woman's lap.

One of Poole's main criteria for choosing topics was how readily and cheaply they could be demonstrated visually. To simulate an atomic chain reaction, he employed a massing of 100 mousetraps. A pair of sugar cubes was perched on each trap so that when triggered, the cubes would launch into the air. Puffed wheat cereal blown about in a jar stood in for electrons in a vacuum tube. To simulate a body in the weightlessness of space, they borrowed a film camera and trick-shot a crew member jumping on a YMCA trampoline and wearing a "space helmet" fashioned from a cake container.

While his aesthetic sensibilities made sure the show was more than just talking heads, Poole's outside-the-academy perspective may have helped in other ways. "Because Poole is not himself a scientist, he sees science as part of culture," LaFollette says. "It's not something isolated in a laboratory that is only for scientists. It is part of our society. So that's a different approach than might be taken by someone who was trained as a scientist and then wanted to become a popularizer."

Few are still around who appeared on the show's early days. But there is Professor John Astin, A&S '52. Though best known for the role of Gomez, the smooch-happy, mustachioed patriarch in the 1960s sitcom The Addams Family, Astin debuted on TV in 1952, on the Science Review, where he played a barker hawking blown glass trinkets at a carnival. The episode discussed how glass blowers make exacting lab equipment and not just gewgaws for the mantel.

"Somehow, the word got out that I did these sorts of sketches and little routines, including one as a burlesque barker," Astin says. "I remember being around the Science Review productions a couple of other times. I may have been an extra or I may have just helped out behind the scenes. I have a picture of me with Lynn Poole. He was a very clever fellow, innovative and always filled with ideas."

View this post on Instagram

But the "shoestring surprise" (and ratings black hole) was destined to be done in by a maturing television marketplace. The episode titled "Seven Years Old" aired on March 6, 1955. It was not a program about child development. The show acknowledged and celebrated the Science Review's birthday. And announced its demise. "The Science Review has lived through this fabulous and amazingly swift development of television—a very exciting period—and we can look back these seven years knowing it's been a privilege to grow up with television," Poole says, perching casually on the edge of his desk. "Today, we come to the end of the Science Review."

The episode went on to quantify television's growth: The country now had 423 TV stations serving some 36 million TV sets. Left unmentioned was that the cash-strapped DuMont Television Network, long struggling to keep up with the Big Three, had folded. Poole thanked the "men of science" who had made the program possible. (Yes, the scant handful of women who'd been guests on the program were not acknowledged.) But he ended on a bright note with mention of a potential new Hopkins TV project called Tomorrow.

That program, later called Tomorrow's Careers, was picked up in 1955 by ABC but aired on sleepy Sunday afternoons. (Even in its hometown of Baltimore, it was sometimes pre-empted by sporting events.) Poole hosted this vocation-focused show where guests spoke about various career paths—archaeologist, industrial designer, dermatologist, airline pilot. Johns Hopkins File 7, which debuted in 1956, represented somewhat of a return to the Science Review form, but now arts and humanities topics were the focus. The name, the show's intro explained, alluded to a "special file that contains provocative information about the experiments and ideas which underlie the purpose of our American colleges and universities." There were shows about Shakespeare and Thoreau, astronomy and elephants, H.L. Mencken and Emily Dickinson; the Hopkins Glee Club sang for one episode, as did folky Mike Seeger. Interestingly, John Astin's father, Allen Astin, a physicist with the National Bureau of Standards and Technology, appeared on the 1959 episode "Measuring Tomorrow" discussing the science of measurement.

Like its predecessors, the show had weak ratings. Parked in its non-prime-time slot, the show was ignored by the national press. But some key folks were watching. A 1958 survey of incoming out-of-state freshmen found that 14 percent had first heard of Johns Hopkins through television. By 1960, President Milton Eisenhower acknowledged on the show that "the business of creating, producing, and presenting a weekly program has become increasingly burdensome." Hopkins' experiments with television officially came to an end.

Out of the spotlight, Poole remained at Hopkins until 1966. University Vice President and Secretary Emeritus Ross Jones, A&S '53, remembers crossing paths with him in the early 1960s: While acknowledging that the Review was largely "Lynn Poole's baby," Jones says that credit for its development should go also to P. Stewart Macaulay, A&S '23, university provost and later vice president, who had hired Poole. "I can imagine Macaulay making it clear to Lynn how important science, medicine, and engineering were to JHU," Jones said in an email conversation. "And Lynn, or the both of them, seeing some exciting possibilities to showcase on the newly emerging television."

The kinescopes of his pioneering programs languished unwatched and decaying for decades, while slick, next-gen science television shows eventually came to the fore. Of course, they all ran on nonprofit public television, which arrived in 1969 to purposefully take on the mantle of TV's "intellectual ghetto." Science shows, it turns out, are also rather siloed affairs: "They are usually produced by a completely different group of people each time, and there's not very much knowledge transfer," Ockert says.

Image caption: U.S. Navy Lt. Cmdr. Malcolm D. Ross, a balloonist and atmospheric scientist, holds a cutaway model of the Strato-Lab, a manned balloon outfitted with a 16-inch telescope to observe Mars. The Johns Hopkins logo is visible on the base of the model.

Image credit: Sheridan Libraries / Johns Hopkins University

Besides having appeared too early and on a doomed network, the Science Review focused on grown-up viewers, a perspective that may have dampened its influence among science programs. And how widely it's remembered. The kids show Watch Mr. Wizard ran from 1951 to 1965. It's titular figure—a science hobbyist played by the show's creator Don Herbert—performed gee-whiz scientific experiments and demonstrations for youngsters. Thousands of Mr. Wizard Science Club sprung up across the country, and the show was rebooted in the 1970s and 1980s. A young Bill Nye was a fan.

It certainly can be said that Poole's program was a part of the cumulative maturation of science TV. Walt Disney launched a series of deep-pocket, full-color science television specials for its Disneyland program, beginning in 1955 with "Man in Space." Three years after appearing with Poole, there was rocketeer von Braun again, surely delighted with the plywood-free, Hollywood-worthy spaceship—replete with actor astronauts—that Walt's team delivered. Disney's 1957 program "Our Friend the Atom" trotted out Poole's mousetrap trick, only with pingpong balls instead of sugar cubes.

The Science Review might have disappeared forever if the arduous process of archiving the collection and creating both video and digital versions of the hundreds of films had not begun in 2003—empowered by a $150,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and $75,000 in private funding. Now episodes could be placed online. For the first time in decades, people can glimpse these black-and-white messengers from an age when the power of science—and the power of television—held limitless wonder.

"One day, perhaps in your lifetime, and I very much hope in mine, men in cumbersome, pressurized space suits will walk very slowly and carefully and enter a rocket," Poole says at the conclusion of the "Man Will Conquer Space" series. "And this rocket will be catapulted up through our atmosphere out into space ... and go to the moon."

And he was right. In 1969, a mere 17 years after the Review brought a plywood rocket and hand-held model spaceships to perhaps television's first earnest discussion of the potential for manned space flight, Apollo 11 delivered two cumbersomely outfitted astronauts to the surface of the moon.

Alas, Poole who had hoped to see it, did not. He suffered a fatal heart attack in his California home three months before this "giant leap for mankind." He was 58.

Poole's obituary in The New York Times called him an "educator on the air" and "this country's most unintentional television personality."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Science+Technology

Tagged science, johns hopkins history, johns hopkins science review