Chris Arnade was an outlier when he arrived on Wall Street in 1993 with a PhD in particle physics. For the next two decades he used mathematical models to make money as a bond trader, until the 2008 financial crash and government bailout made him question his career's value system. He started taking the subway after work to the South Bronx's Hunts Point neighborhood, where he volunteered at a nonprofit organization and began talking with and taking pictures of the people there, often those living in poverty or who use drugs. The Atlantic and The Guardian tapped him to write about poverty, and in 2015 he embarked on a cross-country road trip to stop in small towns void of tourists, news media, and sometimes even Walmarts. He wanted to chat with locals to find out about them, their town, and their concerns.

Image credit: Penguin Random House

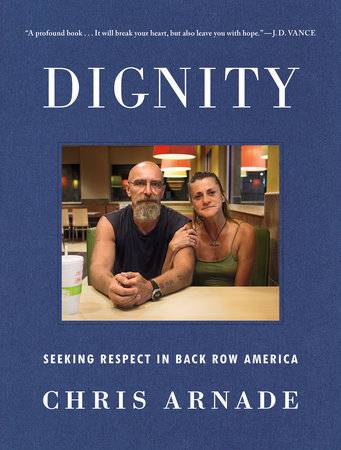

His new book, Dignity: Seeking Respect in Back Row America (Sentinel), is the result of putting more than 150,000 miles on his car from 2014 to 2018, a period that spanned the 2016 presidential election and the first two years of the current administration. He developed his own process for getting to know a place he'd never set foot in. "I would stay in a hotel that was very cheap," says Arnade, A&S '94 (PhD). "And I would spend my time walking around from McDonald's to churches to community colleges—or driving, if need be."

At a McDonald's in Bakersfield, California, he comes into contact with a range of people who would numb their everyday traumas and feelings of isolation with drug use. At a mosque in Youngstown, Ohio, he learns about the importance of faith to a man's sobriety and survival.

Arnade tells these stories in Dignity through a combination of photos and his own first-person reportage. A chapter about understanding McDonald's restaurants as impromptu American community centers is followed by a collection of portraits at various Golden Arches locations: older people playing bingo, a high school soccer team of predominantly Somali Americans in Lewiston, Maine. In the latter image, the young men crowd around a corner table, a few wearing matching blue warm-up jackets, proud and smiling.

"I found myself drawn to places where people didn't necessarily bring a camera, and that helped inform the photos I took because the neighborhoods defined the photography," he says. "I don't think photography alone can do justice to people's stories. Neither can words, so [Dignity] became a combination of the two in a way that I felt filled in the limitations of each one."

Dignity also documents Arnade's own re-education as he wrestles with the inequality we see today by understanding the decades of racism, policy decisions, economic shifts, and political winds that built the country and its cities and towns. It's a history that, for Arnade, seats people in two places in the theater of American society: People privileged enough to sit in the front row and those who don't have the same sorts of employment opportunities or access to quality education or health care, and on and on and on. They are the back row Americans Arnade features throughout Dignity.

Image credit: Chris Arnade

Yes, they're disenfranchised, but they're also thoughtful, politically astute, and diverse of opinion, creed, and culture, and they can't be reduced to a demographic assumption based on how their county voted in the last election. As Arnade writes: "We study poverty and those we left behind with spreadsheets and statistics, believing we are well-intentioned, believing we are really valuing them."

That's a former financial analyst talking about the limitations of big data. "The quantitative methods have big blind spots in them and they need to be balanced against another way of seeing things, which is literally seeing them and dealing with them on a personal basis," Arnade says.

Dignity has earned comparisons to Jacob Riis' How the Other Half Lives (1890), about living conditions in New York's tenements, and writer James Agee and photographer Walker Evans' Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), about tenant farmers during the Great Depression. But Robert Frank's The Americans (1958) is more apt. Frank's images of the country from sea to shining sea mirror Dignity's expansive view.

Image credit: Chris Arnade

More importantly, the Swiss-born Frank was an immigrant looking at America through foreign eyes. Without being didactic, Dignity shows how the distance separating front from back row America is so great they might as well be different countries. Working on the book has made Arnade "far less quick to take experts at face value," he says. "It's made me, I hate to say, somewhat cynical in the sense that the underclass is screwed over at every level, and it often feels like politically it's such an uphill battle that I don't know if it will ever be won. And that cynicism is hard to fight.

"But if there's any regret I have about this book, it's that I didn't get to write about the people I met who are doing wonderful things," he adds, referring to people who live between the front and back rows. "People teaching at community colleges in local towns, librarians, and other people who are doing what effectively is community outreach in smaller communities but not getting a lot of attention for it. The decency and the dignity of all these people give me optimism."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged sociology, photography, politics