When Gabrielle Dean first visited Robert Wilson in 2009 at his home on Maryland's Eastern Shore, her intention was to collect photographs that Wilson wanted to add to the personal papers he had donated to Johns Hopkins' Sheridan Libraries in 2003 and 2004. A postdoctoral fellow who had joined the library staff in 2008, Dean chatted amiably with Wilson as he shepherded her around his St. Michaels home, a modest rancher that he shared with his decades-long partner, Kenneth Doubrava.

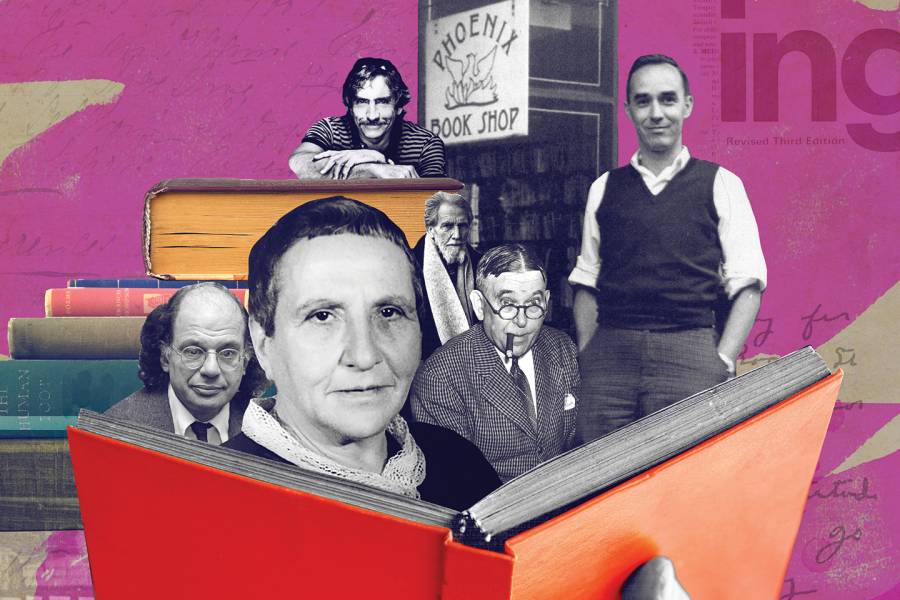

Then Wilson, A&S '43, a well-regarded bookseller, obsessive book collector, and author who for more than 25 years owned and operated the Phoenix Book Shop in Greenwich Village, ushered Dean into his voluminous library, located in a special addition to the house, to show her his collection, notably his Gertrude Stein materials, a spectacular trove of inscribed first editions by the iconic and idiosyncratic 20th-century author—a total of 1,396 volumes, representing 1,187 unique titles, plus much more Stein-related material.

"When I saw those Stein books, I think my eyes got really big as I started to grasp what he had," recalls Dean, the William Kurrelmeyer Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts for the Sheridan Libraries since 2016 and a serious Stein scholar—she wrote part of her 2005 dissertation on the author. "He showed me that all his editions of books by Stein published in her lifetime weren't just first editions, but they'd been inscribed by her to people in her circle, and he let me take a picture of the inscription to Picasso in her book called Picasso. That's when I understood what a thorough collector he was."

Wilson, who died in November 2016, age 94, possessed a voracious appetite for all things Stein—whom he called "my primary passion in modern literature"—assiduously acquiring virtually everything she wrote: books, plays, poetry, magazine articles, and correspondence. He sought out her works from their rawest form (handwritten and typewritten manuscripts with scrawled corrections) to their next stage (uncorrected proofs) to final publication. Even a Braille edition of her 1940 memoir, Paris France.

Image caption: Gertrude Stein pillow, artist unknown.

Image credit: The Robert Wilson Collection of Gertrude Stein, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University

This bonanza also brimmed with antic curiosities, including a Stein paper doll. "I shudder to think what Gertrude would have thought about that," Dean notes with a laugh, "but it's accurate: She's wearing sandals and a vest." Also, a beer mug in the shape of Gertrude's head (a Stein stein with a tiny Alice B. Toklas, Stein's life partner, affixed to its handle), finger puppets, refrigerator magnets, a wristwatch, T-shirts, tote bags, coffee mugs, and a pillow embroidered with her baleful stare.

"There was a whimsy about Wilson's collecting, definitely a joyfulness about it," Dean says, "as well as this very serious and dedicated scholarly collecting impetus."

By the time of Dean's visit, Wilson was in his late 80s and already had sold—or was preparing to sell—his equally impressive collections of works and related ephemera by Ezra Pound, Edward Albee, Allen Ginsberg, and other modern literary leviathans. Surveying Wilson's Stein bounty, Dean began to fantasize that maybe Johns Hopkins could acquire that collection.

Born and raised in Baltimore, the only son of a hardware-store-owner father and homemaker mother, Robert Alfred Wilson, not of his own volition, made headlines as an infant when he was selected "Most Beautiful Baby of 1923" at the Maryland State Fair.

"My grandmother entered him in this contest," explains Joanne Eich (Bus '92, MS), Wilson's niece. "She wanted to win the 20 bucks that was second prize, but he won first prize, so he got a silver cup instead, which I still have in my bedroom. She was so disappointed. As he aged, he would tell anyone who visited him this story. 'Let me show you my trophy,' he'd say."

Known in his family as "Rocky"—a consequence of Eich, the daughter of Wilson's sister Merle, garbling his given name as a little girl—Wilson graduated from City College, a Baltimore high school, then matriculated at Johns Hopkins in 1939 at age 17.

His book-collecting passion had been ignited the year before when he attended a lecture at his high school given by the Baltimore-based cultural critic and journalist H.L. Mencken. Soon thereafter, the teen bought a half dozen out-of-print Mencken first editions at a local bookshop.

"Then it occurred to me to try to get them signed," Wilson wrote in an introductory essay in The Robert A. Wilson Collection of H.L. Mencken, a 2006 limited-edition catalog of Mencken works donated by Sheridan Libraries benefactor and former Johns Hopkins trustee Richard Frary, A&S '69, which reside at Hopkins' George Peabody Library. "Finding, to my surprise, that Mencken had an open listing in the telephone directory, I was brash enough to telephone him and ask him if I might bring my little collection over for signing."

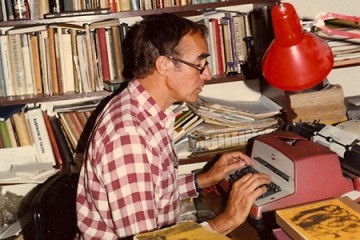

Image caption: Robert Wilson in the Phoenix Bookshop in 1979

Image credit: CHRISTOPHER P. STEPHENS

Mencken answered the phone himself, and, while courteously demurring a visit, agreed to sign Wilson's books if they were mailed to him. "True to his word," Wilson adds, "they came back promptly, nicely inscribed."

Over the next several years, Wilson actually worked, in a tangential fashion, with Mencken, beginning with a summer job after high school as a research assistant in the morgue (clippings room) at The Sun, Baltimore's leading daily newspaper and Mencken's employer. On several occasions, Mencken marched into the morgue asking the 17-year-old Wilson to check facts for stories he was writing (work that ultimately appeared in Mencken's 1941 memoir, Newspaper Days). A few years later, when Mencken failed to find a reference book he needed at the city's public library, he showed up at Gilman Hall, where Wilson worked part time in Hopkins' library to help pay for his tuition, and asked the student to retrieve the elusive volume.

"That was the last time I ever saw him," Wilson wrote in his Mencken essay. "But when Newspaper Days was published, I sent it to him for signing, with a note reminding him of my having checked data for him at The Sun. His inscription in the copy was far beyond anything that I could have hoped for: 'Robert Wilson. Good luck! H.L. Mencken. And with thanks for his help in the Sun Library.'

"Of all the books in my entire library, this is my most cherished. And that is why it is the one Mencken title that I have held out. You'll have to get it from my executors."

At Johns Hopkins, Wilson participated in a temporary accelerated program that included summer classes, an effort to graduate those male students who had been drafted by the military but were studying on a deferment as quickly as possible so that they could serve in World War II. For Wilson, that involved a German language immersion program (he had taken German in high school), and, upon graduating from Hopkins in February 1943 with a degree in English and American literature, entering the Army and diving into more German immersion classes in New York City.

The Army then shipped him to England to translate German technical documents, many pertaining to weaponry. But in December 1944, when fresh troops were desperately needed to fight in the Battle of the Bulge, Wilson, a corporal, was transferred to the infantry. Wounded, he was awarded the Bronze Star and Purple Heart, and, after recovering, marched through Europe and was among the first Americans to cross the Elbe River into Germany and meet up with Russian soldiers as the Allies neared victory.

After peace was declared, he witnessed Russians burning books in Germany, and salvaged an early text—published in 1477, not long after the invention of the printing press—before it could be hurled onto a bonfire. "It was part of a six- or seven- or eight-volume set describing canon law, made of vellum," Eich says. "When my cousins and I were young, he always said, 'Look at this, kids—it's the oldest book in the world.' But we have to keep in mind he loved to embellish. I mean, he was a master at it."

Back home in Baltimore, he decided to continue his lit studies at Johns Hopkins. According to Timothy Murray, head of Special Collections at the University of Delaware's library and a longtime Phoenix Book Shop customer, Wilson met with unanticipated resistance: "He loved to relate the tale of how he went in for an interview, and one of the people in the English Department said that, basically, they didn't think that he would be able to make it in the field of literature. That always stuck with him—and it was one reason why he [eventually] went into his career as a bookseller."

Spurned by Hopkins, Wilson joined the State Department's diplomatic corps, first working in Poland helping people obtain passports to emigrate to the United States. "He said it was a very frightening time because there were so many people that wanted to get out," Eich notes. "He would be in his little apartment, and people were knocking on the door in the middle of the night, saying, 'Help me, help me.'"

From Poland, he moved on to a post in South Africa, but when he began to encounter hostility and discrimination in his job, he resigned. "If you were gay, you were not welcome in branches of the U.S. government," notes Wilson's nephew Jonathan Metzger, the son of his Uncle Rocky's other sister, Sidney. "That would potentially be used against you to do things against your will."

Tall, thin, and handsome, Wilson, in the mid-1950s, moved to New York, where he put his German language skills to use as the office manager of a company that sold cuckoo clocks made in the Black Forest. Simultaneously, he steeped himself in the city's burgeoning post-war theater and poetry scene and, not incidentally, indulging a newfound enthusiasm for book collecting. One of his favorite haunts was the Phoenix, and in 1959 he initiated an on-again/off-again campaign to buy the shop, succeeding in 1962 when its owner—who had put off Wilson twice before—finally consented.

Wilson gradually set about transforming the Phoenix from a broad-based bookshop into a literary one that specialized in his twin passions—first editions and new poetry. Robust sales of the former compensated for the barely break-even receipts produced by the latter. He also fashioned the shop into a salon for a galaxy of current—or soon-to-be—literary brahmins and illuminati (especially among the Beat writers), for whom Wilson often served as an apostle, den mother, and, most importantly, publisher.

"It was fully a part of the 'trail of bookstores'" in New York's bohemian downtown, recalls Ed Sanders, poet, political activist, and core member of the 1960s avant-rock band The Fugs. "A good number of poets sold their books in impecunious times to Wilson. I remember being particularly interested, standing for hours reading The [Ezra] Pound Newsletter in the Phoenix. As a rare publication, it was beyond my financial means, so I stood and read. I never saw him angry. He was pretty smooth in demeanor."

Under Wilson's stewardship, the Phoenix evolved into a place whose name, invariably, became prefaced by the adjective legendary.

There was the time, for instance, when Allen Ginsberg washed dishes for an otherwise overwhelmed Wilson in the shop's tiny rear kitchen.

And there was the time when playwright Edward Albee, author William Burroughs, and poet Gregory Corso serendipitously appeared in the shop at the same time, with Wilson introducing Albee to Burroughs.

And Sanders running off copies of his provocative journal Fuck You/A Magazine of the Arts on vividly colored paper—bought with money advanced by Wilson—on the mimeograph machine in the shop's back room.

In 2001, Wilson recounted all of this—plus interviewing Alice B. Toklas while sipping tea in her Paris apartment; his visit to the garrulous Olga Rudge (Ezra Pound's longtime mistress, mother of his daughter, protector of his reputation, and, in her own right, respected violinist) at the couple's house in Venice, 10 years after the poet and critic's death; his packing and removing a gargantuan number of books owned by W.H. Auden in the housekeeping-challenged poet's New York apartment while buying a major portion of Auden's personal library—in his breezy, highly anecdotal, and occasionally gossipy Seeing Shelley Plain: Memories of New York's Legendary Phoenix Book Shop. (Wilson pinched its title from a stanza in Robert Browning's poem "Memorabilia.")

Wilson's first paying customer at his shop was Frances Steloff, doyenne of the Manhattan bookshop community as proprietress of the Gotham Book Mart. In effect, with that sale, she bestowed her benediction on Wilson. "I'll never forget the graciousness of that gesture," he wrote in Seeing Shelley Plain.

In addition to walk-in business, Wilson courted patrons via catalogs. His first offered fiction, poetry, literary criticism, periodicals, art books, and a tiny selection of first editions, as well as rare material: a two-page typed Burroughs letter with a postscript from Ginsberg; a 16-page typed poem by Ginsberg, marked with revisions; a trio of paintings by the experimental poet and novelist Kenneth Patchen; and four drawings created by Jack Kerouac for an unpublished comic strip.

He acquired new poetry from the writers themselves, including many notable Beats. He also published their work under the shop's private imprint, with pamphlets by Corso, Ginsberg, Amiri Baraka (then known as LeRoi Jones), and Michael McClure, among others, plus Black Mountain poets Robert Duncan and John Wieners, and, finally, moderns not associated with any specific movement: Marianne Moore, Auden, Richard Wilbur, W.S. Merwin, and Elizabeth Bishop.

Additionally, the Phoenix issued a series of bibliographies, compiled by Wilson himself (Stein, Corso, poet Denise Levertov) and others. It also published what Wilson termed "Christmas keepsakes." These limited-edition chapbooks, written by Wilson, were sent to cherished customers and friends as holiday gifts, and usually recounted his globe-spanning literary jaunts: his tea with Toklas; his pilgrimage to Pound's home; his trek to a remote village in South Africa to find the titular character of H. Rider Haggard's She; and memorable local exploits such as his rummaging through Auden's library; his refrigerator-and-pantry-emptying lunch (tuna salad sandwich, Fritos, canned pears) at Moore's Brooklyn apartment; and, while lolling on Fire Island, his serendipitous discovery and acquisition of William Faulkner's original typed manuscript of Soldiers' Pay, the author's first published novel (including an alternate, previously unknown conclusion), as well as 13 poems and 15 short stories by the young author, some unseen until then.

Unsurprisingly, several holiday keepsakes pertained to Stein. In addition to Wilson's audience with Toklas, they include one that he sent out in 1959 (pre-Phoenix) that consisted of Stein-penned postcards plus a letter written by her and Toklas; also, an especially curious one he issued in 1999 (post-Phoenix) of an interview conducted between Stein and recent Stanford University graduate Robert Gros (an extraordinary life awaited him, but that's another story entirely) that was conducted via passed notes during a 1935 flight from Stanford to Chicago.

Over the years, the Phoenix thrived, buoyed by Wilson's innate enthusiasm for literature and his learned-on-the-job business savvy, which drew on his father's experience as a successful merchant. "Entrepreneurially, he knew the value of, basically, every book," Metzger notes. "He had a photographic memory for books—he knew every edition that was ever made."

Wilson extended the shop's reach into the lucrative institutional market, selling new works by established and emerging poets and authors to American universities and foundations. But by the early 1980s, worn down by New York City's soaring crime rate—he was burglarized four times at three different residences and on several occasions at the Phoenix, including twice at gunpoint, plus mugged emerging from the city's subway—Wilson reluctantly decided to sell the bookshop. Recalls his niece Eich, "He said, 'I've got to get out of this city.'"

In 1984, he bought the home in St. Michaels, situated on a picturesque inlet not far from where his parents had moved from Baltimore in 1954. Initially, he spent time there with Doubrava—a composer, performer, teacher, director and producer of music and theater, and sometime Phoenix employee—on summer weekends and for a month each winter. He also listed for sale the five-story Manhattan brownstone (books shelved floor to ceiling in one immense room, with protective window coverings to shield his collection from damaging sunlight) where he and Doubrava lived. And he set about finding a buyer for the Phoenix, ultimately coming to an agreement with a bookstore newbie very much like himself 25 years earlier.

But when the shop's landlord scuttled that deal at the last minute, a dispirited Wilson eventually eliminated the Phoenix's existing inventory via two quickly assembled catalogs and a half-price in-shop sale, unloaded what remained to a Washington, D.C., book dealer, and, in October 1988, shuttered the place.

Wilson's unbridled dedication to all things Gertrude Steinian began innocently enough in the late 1950s courtesy of his close friend, occasional lover, sometime Phoenix employee, and, briefly, roommate Marshall Clements—Wilson dedicates his memoir to Clements—who bought a copy of Stein's The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas and read aloud from it to Wilson one evening. "Fits of laughter made our progress very slow," Clements wrote in an essay in The Phoenix Book Shop: A Nest of Memories, a 1997 chapbook that, Festschrift-style, celebrates and memorializes the shop. "But Bob was hooked. He immediately began searching out Stein's books, and it was then that his career as a serious book collector began in earnest."

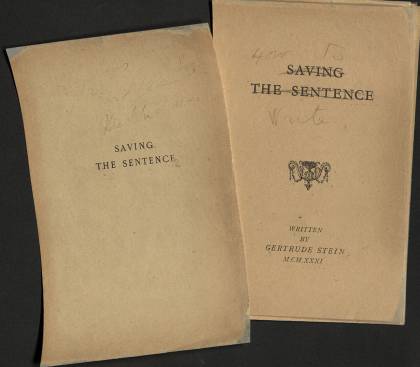

Image caption: Proofs with Stein’s corrections of "How to Write," published by the Plain Edition.

Image credit: The Robert Wilson Collection of Gertrude Stein, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University

Back then, next to none of her 60-plus books remained in print—a Stein revival did not begin until the early 1970s—forcing Wilson to scour catalogs from U.S. and European booksellers for her work, mostly first editions, because only a handful of her books sold sufficiently to justify subsequent printings.

Wilson also tracked down letters and postcards handwritten by Stein; uncorrected proofs of her manuscripts; magazine articles written by her; record albums of Stein reading her own work; transcripts of radio interviews with her; clippings of what seems like every newspaper and magazine article written about her; announcements of, catalogs from, advertisements for art exhibitions and readings and musical productions associated with her work and life; and countless photographs of Stein, her family, and friends, both casual and formal, the latter including portraits made by Man Ray and Carl Van Vechten.

The immensity of all this comes as no real surprise. Wilson, after all, was the man who had written the definitive Stein bibliography and first republished her earliest work, dating from her time as a medical student at Johns Hopkins as the 19th century segued into the 20th.

Stein spent four unsatisfying years, 1897 to 1901, as a graduate student at the School of Medicine, after earning a degree in philosophy at Radcliffe College, where she researched normal motor automatism (the study of a person's conscious and unconscious attention). In 1896, "Motor Automatism," an article written by Stein and Leon Solomons, appeared in the journal Psychological Review. Two years later, Stein, under a solo byline, contributed "Cultivated Motor Automatism" to the same periodical. These two articles constitute her initial published work. Under the auspices of the Phoenix imprint, Wilson, ever the Stein votary, republished the two papers—the first to do so—in pamphlet form as Motor Automatism in 1969, five years prior to his magisterial bibliography of her entire collected works.

But Stein failed to complete her degree at Johns Hopkins, blowing off her studies in her junior and senior years, and flunking two courses in the latter, discouraged by and bristling at what she considered the overt and covert sexism and anti-Semitism she experienced from her professors and male classmates. "A couple of Stein biographies have addressed why didn't she finish [med school]—there's lots of ideas about that," Dean notes. "She says she was bored. And it might not have been the friendliest place to be a woman medical student.

"Robert might have been one of those people who was just impressed with her brazen and forthright treatment of the language," Dean adds. "But he also might have been impressed with her as a personality—the amazing life that she and Alice made for themselves."

Dean's pipe dream of bagging Wilson's deep and broad collection of Stein-signed first editions, plus the welter of materials related to her life and work that he had amassed over five decades, lasted mere moments during their initial meeting at his St. Michaels home.

"He anticipated my question by telling me very firmly that the collection was already spoken for—that it would go to the University of Delaware," she recounts now. "And I tried to recover myself, tried not to act too disappointed. Here I was finally encountering the premier private collector of one of the two figures with whom I was a scholar [Emily Dickinson is the other], so I was really kind of crushed. But I think he also was delighted how cool it was that I didn't just appreciate it strictly from a collection standpoint."

Then, three years later, in 2012, she received an out-of-the-blue phone call from book collector and philanthropist Mark Samuels Lasner, a senior research fellow at the University of Delaware, who told her that his school was passing on the acquisition of Wilson's Stein books and papers. Johns Hopkins, she then learned from Sheridan Dean Winston Tabb, had all along maintained the right of second refusal on the collection. "We knew it was going to be a steep price," Dean explains, "because this was going to be one of his [Wilson's] last sales. And while for some people the joy might be in donating it, Robert Wilson was a lifelong book seller."

Price, in fact, had scared off the University of Delaware. With Delaware out of the picture, Hopkins eventually struck a deal with Wilson, and Dean and several library staffers packed up the shelves-groaning Stein books and materials in 2015, including that evil-eye Stein pillow: "One of my colleagues was pretty sure that the pillow was watching him as he packed boxes and carried them out to a van," she recalls.

Wilson's Stein trove exponentially expands Hopkins' existing collections relating to the author: These include records at the School of Medicine's Chesney Archives pertaining to her medical student years, and, in a kismet connection to the newly acquired works, the 76 volumes that constitute the Devery Collection, purchased by the university in 2007 from the theatrical producer Mary Ellyn Devery, who staged the debut of the one-woman play Gertrude Stein Gertrude Stein Gertrude Stein. Those books were curated for Devery by Wilson, who performed this kind of service for book collectors as a way to augment his income from the Phoenix. "It's a robust collection," notes Dean, "but I'll bet you anything that Robert already had all of those editions."

But it is dwarfed by Wilson's nearly 1,400-volume personal Stein stash. "What this collection offers, maybe, is a soup-to-nuts view of Stein because there are a couple of books that are actually from her library when she was a young person," Dean says. "Any scholar who wants to just dabble in some manuscripts, chances are it's easier to just go to the Stein and Toklas papers at Yale University's Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library because it's very huge. And there's also a sizable collection at the University of Texas at Austin. But I don't know if those other collections are as rich in the material related to her legacy. I don't know that any of them have the artifacts or the generations of experimental writers and artists who feel indebted to Stein. What's amazing about this collection is that there is material in it that scholars have not had access to before, including proofs of work, a great way to understand the evolution of a text.

"And while I think the Wilson collection has a value for scholars, it also has a value for the institution, just to recognize and bring home one of our more illustrious almost alumnae."

Once Wilson reluctantly closed the Phoenix, he permanently settled into the St. Michaels rancher, joining Doubrava, who had lived there full time since the 1985 sale of their New York townhouse. Something of a refined hoarder, Wilson now had ample time to dote on his myriad wide-ranging collections. These included (deep breath): 18th-century antique wine glasses; Staffordshire china; Wedgwood china; Persian carpets; needlepoint; Russian icons in the form of a cross; 17th-century Turkish dueling pistols; Egyptian antiquities; pre-Columbian art; modern art; opera records; and stamps, a hobby that dated from boyhood. According to Eich, the sale of one stamp collection allowed Wilson to purchase the St. Michaels house with cash.

Wilson's pack-rat fever included saving seemingly every letter and postcard he received from family members, friends, poets, and business colleagues. His personal papers at Hopkins overflow with all of those.

What's more, he donated a blizzard of paperwork from the Phoenix—a total of 64,000 items—to the Lilly Library at Indiana University, the first higher-ed school to engage the bookshop's services for newly published poetry and fiction.

Meanwhile, Wilson never stopped reveling in literature. He sold newly acquired works via catalogs; curated and appraised collections for institutions and individuals; lectured on the Beats, Stein, and other poets and authors; wrote scholarly articles for scholarly publications; and, methodically, found welcoming homes for his library's first editions and affiliated author esoterica. And he traveled extensively, either solo or accompanied by Doubrava, whom he married in 2013 (he was 91, Doubrava 82); ultimately, he visited every continent, including Antarctica.

Throughout his life, Wilson, a diehard Democrat, remained politically active, especially so after he closed the Phoenix. In the 1990s, he worked in the Clinton White House as a volunteer. According to Eich, "He liked Bill, but he was a real Hillary fan," reading and rereading her 2003 memoir, Living History. "I had to tell him before he died that Hillary won [the 2016 presidential election] because he would have been devastated [to learn the truth]."

Wilson suffered from dementia by then and lived in a nursing home; he died in late November, three weeks after the election. (Doubrava had died in 2014.)

So, what happened to his "most cherished book," Mencken's Newspaper Days, which Wilson vowed to keep until death did them part? It would be nice to report that it landed at the Peabody Library, joining all the other Wilson Menckeniana, but the book has moved on to unknown hands. "Rocky did hold back a few Mencken books," Metzger, his executor, allows somewhat sheepishly. "They would have been shipped to Cummins [a rare book dealer] in New York City to sell. I did not know that it was inscribed to him."

Dean notes that collecting has long-term effects. Collections of books can reveal fascinating attitudes and values and changes over time, and serve as time capsules, protecting works that were never popular in their own time until there is a readership ready for them.

"I think all of these secret powers of collecting appealed to Robert," she says. "He positively sparkled when he talked about a scarce imprint or inscribed first edition or one of the many other kinds of objects he had noticed, appreciated, and rescued. By putting his beloved books and artifacts into collections, where individual items inform each other, he made each one more durable and comprehensible. And that's the gift to us: not just the materials, amazing as they are, useful as they will be for all kinds of research. But the assembling of those materials—the example he has provided of dedicated, meticulous, astute, ingenious, ardent collecting. That was his way of passing on his love and knowledge to the future."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged sheridan libraries, books, archives