Geneva Keaton is no adrenaline junkie, no Richard Branson, Evel Knievel-type who can't settle down unless she's plotting some bigger, better, push-it-to-the-limits stunt. Heck, she says she's not even a natural athlete.

In truth, says Keaton, A&S '97, she's a little measured. What drew her so strongly to mountain climbing that she spent the last seven years of her life—along with hundreds of thousands of dollars—climbing the tallest peak on each continent was not a need to push her heart rate up but, paradoxically, to bring her stress level down.

"I like getting away from things," she says. "I like the challenge of it. And I like how simple it is when I'm on the mountain. I completely disconnect. I don't worry about emails or work. All you're worried about is sleeping, eating as much as you can, drinking as much water as you can, and working hard every day to get to the next camp or do the next carry. It's just very focused on survival—survival and getting to your objective. I'm not worried about anything else. It's like an escape."

Climb, eat, sleep, repeat, she explains. No earbuds providing a soundtrack to the experience. Not much conversation as she goes, despite the fact that she is doing all this alongside her boyfriend of 17 years, Brian Cheripko. Nothing but her, her thoughts, her strength, and her determination to succeed. "Step, 1, 2, 3. You count," she says, of her footsteps on the mountain, taken to maximize efficiency as she climbs higher and the air gets thinner. "You're taking your time."

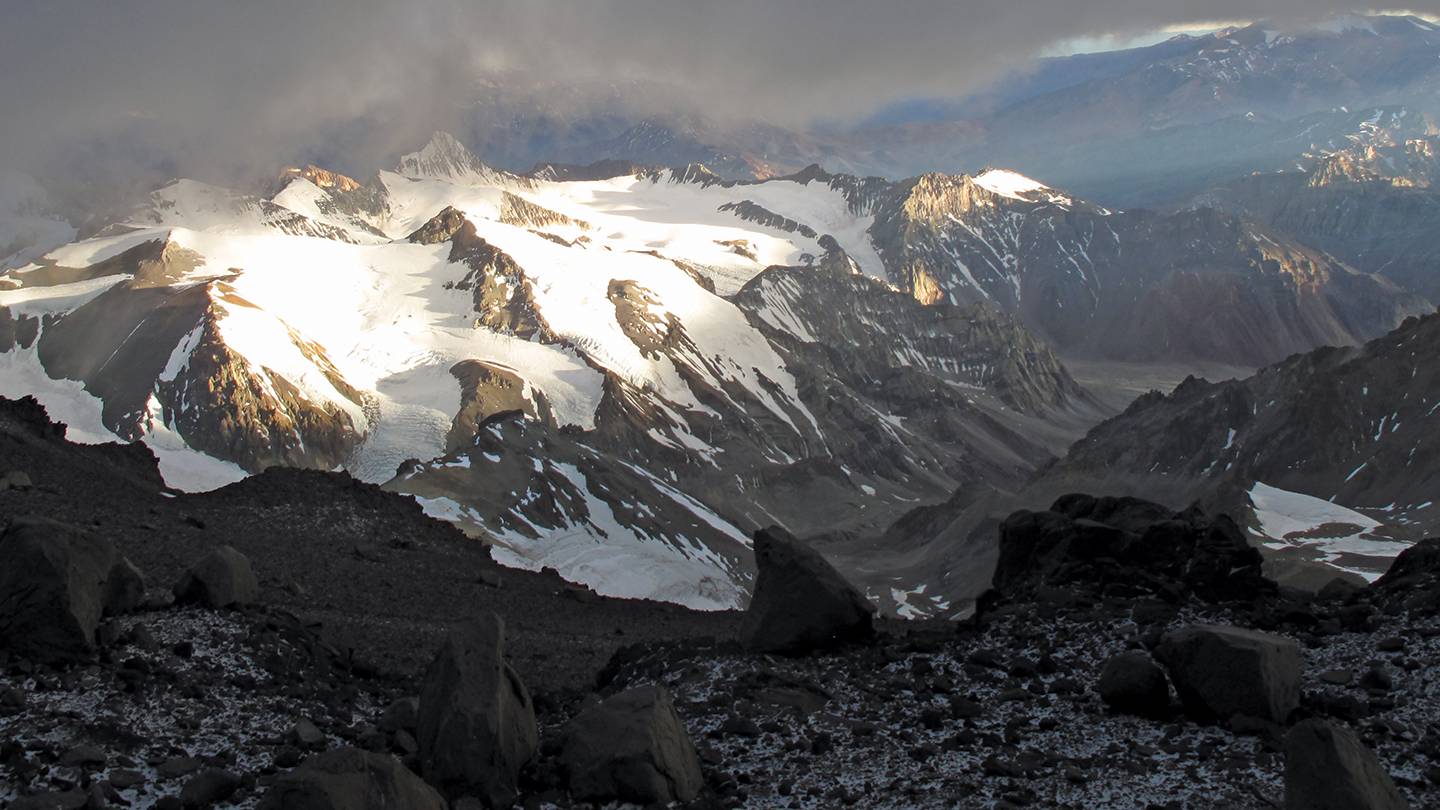

Image caption: Aconcagua: “Our view looking out from high camp as we contemplated our summit attempt the next day," says Keaton. "It was a chilly evening with a layer of clouds hovering over us. I had a feeling it was going to be a very long, cold summit day.”

In her flatland life, Keaton lives in San Diego, where she works as chief operating officer of ANSOL, a consulting company Cheripko founded that provides engineering services and program management to the Navy. She says she's always enjoyed hiking, but it was Cheripko who got her into doing it at high altitude. The couple started making annual treks up California's Mount Whitney, whose 14,508-foot elevation makes it the tallest summit in the contiguous United States. After several years, Keaton came across a magazine article written by someone who had just climbed Kilimanjaro in Tanzania. Fascinated by the writer's description of the adventure and the people encountered along the way, Keaton was in. The couple began training, and she started reading up on what to expect.

She then found the book Seven Summits by Dick Bass, Frank Wells, and Rick Ridgeway. In it, amateur climbers and businessmen Bass, 51, and Wells, 53, record their attempt to achieve a lofty dream: climb the highest mountain on each continent. Keaton ranked the climbs from easiest to hardest. The altitude at 19,341 feet shouldn't be underestimated, but Mount Kilimanjaro's seven-day jaunt required little more than a good pair of shoes, a few layers of clothing, and a strong cardiovascular system. At 29,029 feet and taking two months, Everest is considered the toughest of the seven summits and would be the most expensive, requiring $65,000 paid to the guide service. She'd need to invest in a significant amount of equipment too: trekking poles, crampons for climbing on ice, layers of waterproof clothing, a down parka, lots of socks and less underwear than you might think (it's often a casualty when trying to reduce the weight of your gear), plus 10 bottles of oxygen per person for Everest alone. In each gear pack, she left room for a few luxuries: deodorant, face wipes, and moisturizer. "I don't care how much weight it is, I'm bringing it," she says with a laugh.

On September 12, 2011, Keaton made it to the top of Africa's tallest peak, Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania. Aconcagua in Argentina was next, on December 16, 2012, followed by Mount Elbrus in Russia, considered the highest European mountain, on July 18, 2013.

Denali in Alaska, up next, required two attempts owing to an avalanche hazard just above high camp. The second time was even harder, Keaton says, because she knew all too well what she had gotten herself into. It took nearly three weeks, climbing six to eight hours a day. Like many of the summits, it requires a "cache and carry" system, meaning you shuttle some of the equipment from camp 1 up to camp 2, bury it in the snow, tag it so you'll be able to find it later, then go back down to camp 1. Repeat until all equipment is at camp 2, and so on, work- ing the way up the mountain. It's a way to lighten the load, but it's also crucial for acclimatizing to the elevation.

On June 10, 2015, Denali summit day, an exhausted Keaton was about three hours from the peak when she hit a mental wall. "A lot of times, when you're hiking or climbing, it's very monotonous," she explains. "It's you and your thoughts. A lot of people think when you're climbing with a group of 8, 9, 10 people that you're talking all the time while you're climbing, and you're really not." On Denali, for instance, they were clipped in to each other, about 30 to 50 feet apart, as they traveled across glaciers. The distance ensures that if one person falls into a crevasse, everyone else can self-arrest to keep the person from falling down farther. Had the group been walking right behind one another, chances are if one person fell, the whole team would be dragged down. "Nobody's talking to each other," she says. "You're there with your thoughts, trudging along, staring at your feet for hours and hours and hours. It is a mental challenge." You can't space out either, she says, because it's essential to maintain a specific amount of slack in the rope. You need to keep your feet moving, she told herself. Keep pushing.

Image caption: Denali: “A view of the clouds from high camp at approximately 17,200 feet," says Keaton. "You can see the tents of some of our neighbors surrounded by snow walls, which create a barrier from the wind.”

After a successful summit, the group was making its way back to high camp in the Alaskan summer twilight. It was hard to see. They were clipped in together, each separated by about a few dozen feet of rope. "At some point, I got yanked off my feet," she says. "I think I literally flipped through the air and landed on my face, and I didn't know what happened until later. But for a while, we were just worried about finding my pole and getting myself together and back to camp." She later found out that Cheripko had slipped on an icy patch, and the guy standing next to him hadn't fully clipped in yet, so when he fell, the rope was yanked and took her down from behind.

Keaton says of Denali, "It's honestly one of the ones I'm most proud of, just because it was so hard, physically, for me. I'm fairly petite, I'm about 125 pounds, 5-foot-2, so carrying the amount of weight that I did, up that mountain for three weeks, up and down the mountain, it was hard for me, but I did it."

She checked off Vinson Massif in Antarctica on January 6, 2016, after the group was dropped off by a chartered Cold War–era Russian cargo plane. Then came Carstensz Pyramid on West Papua, representing Oceania, on October 16, 2016.

Image caption: Carstensz Pyramid: “My boyfriend, Brian, is seen here (right) crossing the Burma Bridge," says Keaton. "Everyone has a slightly different technique to cross this bridge, but Brian opted to turn his feet sideways as he walked across the cable. This was quite a feat for him because he has vertigo.”

Finally, on May 22, after 57 days of climbing on Everest, Keaton became one of the few people ever to have reached all seven summits. Though there is no official tally, and a website where climbers can self-report the achievement was last updated in 2016, Keaton believes she is among the first 100 women to have knocked out all seven. Atop Everest, she stood on a long, narrow path—careful that her pack didn't slide off the mountain—looking out at the endless sky. "I'm not sure if my mind was playing tricks on me, but it seemed you could almost see the curvature of the Earth," she says. She posed for a photo against a backdrop of ornaments left by previous climbers: prayer flags, a statue of the first monarch of the Kingdom of Nepal, a bell. She snapped another photo, this time with her face mask off, so that the Nepalese government could verify her identity and send her a certificate of completion.

Image caption: Everest: “Sitting on top of the world," says Keaton. "Behind me (left) is a statue of King Prithvi Narayan Shah, considered a symbol of unity in Nepal, which was carried up a few days earlier by Pemba Dorje Sherpa.”

"It was—what's the right word—a little sobering, I guess," she says. "It's not like you're standing up there, dancing around. We hugged each other, and we were all happy and proud of ourselves. But some people say, 'So, are you going to conquer that mountain?' I don't think we conquer any of these mountains. I think the mountain just lets us climb them. Or they don't! It decides, 'Today's just not your day.' So it's more a sense of respect that you've made it up there, a sense of pride but not a feeling of, 'I conquered this mountain.' I've conquered a lot of things, but not a mountain."

And then, after 45 minutes, she began the long trek down. Twenty minutes outside of base camp, one of the cooks presented the group with bottles of beer and Coca-Cola. "That was the best Coke I've had in a long time," she says. Soon, she got a much-needed shower, recovered a healthy appetite, and within a few weeks gained back some of the 12 pounds she lost. She would no longer have to defecate in something called a WAG bag. She wouldn't stumble across any of the more than 200 corpses that have been left on Everest because of the enormous effort and expense required to get them off the mountain. But when she found herself back at her desk the following Monday on a teleconference call, she says she couldn't help but think, "This is a little bit of a bummer."

Keaton says what's next for her is more mundane. She's putting expensive climbs on hold for now to build up her retirement savings. And she's cleaning out her closets. "I've realized how much excess we all have that we don't need," she says. "It comes back to the simplicity of the mountains. I have my one or two comfort items while I'm on the mountain, but after that, it's your clothes, what you're eating, your gear, and that's about it. I think about that every time I come back from one of our trips. I'm actually, right now, on a purging rampage. I'm purging a lot of junk and things out of my life. We have so much stuff we don't need that we accumulate over time. I think about that. And I also think about ways to make my life simpler. Sometimes you can't avoid it—there's work, life, family—but I have really tried to focus on making my life a little more simple, and trying not to worry about the small stuff. It does help you put life in perspective."

Online exclusive: What it's really like to climb a mountain

Training

When Keaton is within six months of a climb, she trains five to six days a week. Her regimen depends on the mountain itself—the type of terrain, whether the climbers will be carrying their own packs or enlisting the help of porters, etc. Staples of her workout routine include running, swimming and strength training, as well as using the step mill and elliptical. Throw in her usual two hikes each weekend. For Denali, which requires climbers to carry their own gear, Keaton included more strength training. For Everest, which is less about weight and more about endurance, she focused on swimming and running.

Food

Keaton says the meals during her climbs were actually really good. Many people lose their appetites at high altitudes, so the expedition company goes out of its way to provide the most appealing food possible. In Denali, the guides brought rib-eyes. For Kilimanjaro, meals included chicken, pastas, salads, fruits, and breads. For Everest, they had two camps with a full kitchen and chef, who prepared steak, chicken, and even sushi.

Climbing process

The typical climb session lasts four to six hours, with rest breaks every hour or so, when climbers take time to hydrate and eat. Keaton says she follows the principle of "climb high, sleep low," which helps acclimatize to high altitudes. It's all about efficiency, she says. You move slow and steady (that goes back to the "step 1, 2, 3" bit in the story) so that you don't lose your breath. But move too slowly and you'll hold up the whole group, she says. To avoid a head rush, climbers are even told to squat down rather than bend over while on the mountain.

Going to the bathroom on a mountain

Using the "facilities" on the mountain isn't always easy. On some mountains, there are designated stations—separated by pee and poop—in order to control the, uh, litter. That means climbers have to sometimes make two stops to relieve themselves. Keaton says she carries a pee bottle for when she has to go in her tent at night. Don't worry—she keeps duct tape on that bottle's lid so she doesn't confuse it with her water bottle. And if you're traveling as a roped team when the urge hits, Keaton says, you basically just tell everyone to look away while you go because you can't unclip in the middle of climbing on glaciated terrain.

Climbing with a significant other

Basically, you're climbing on your own on a mountain, says Keaton. Romantic partners can stay in a tent together each night, when they get to talk about the day. "If you really want to know how you can deal with another person, sleep in a tent with them for three weeks, or even two months like we did," Keaton says. "You are climbing as a team, but you're also climbing as an individual. Everyone has their own mental struggles—he had different things he had an issue with, and I had my things I had problems with."

Posted in Student Life, Alumni

Tagged alumni