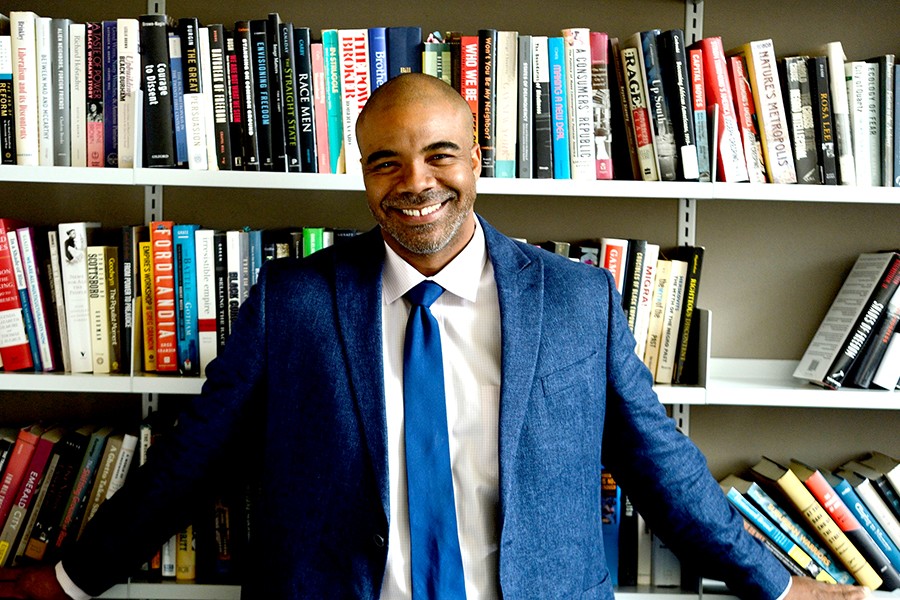

For the second episode of The Known World, the Johns Hopkins Magazine podcast, we talk to historian Nathan Connolly, who co-hosts the podcast BackStory, about fashioning narratives out of historical events—what is gained and what is lost in approaching history as story. Listen to the episode, or read the excerpt below.

There are many ways to organize historical information. Organizing history as story, especially narrative story, is one. What is gained from that approach?

I think it's really important to give people who are reading historical work a grounding, in some ways. Narrative is partly a way of making sure that characters are living, are breathing, and that readers can see where events are unfolding and how they're unfolding. The thing about narrative is that we talk in narratives all the time, even if we're not entirely sure that we're doing it. So it really ends up falling on scholars who are working through archives to stitch together enough information to be able to tell a story, and touch the story that most people already have in their heads for whatever event they choose.

Conversely, anytime we create a story, we're selective in what we include, what we emphasize. We're crafting something. Does fashioning historical narrative distort the true past?

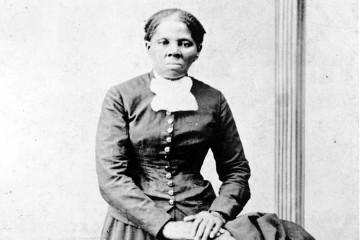

Yeah, absolutely. I think one of the things that's most hazardous about writing these narratives is that you have to make choices. That comes with the territory. And so the question becomes, What justifies the selection and the choices that you're making? There's a really important book called Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History, written by Michel-Rolph Trouillot, who was an anthropologist here at Johns Hopkins. What he talks about is the need to be mindful of the fact that power enters at every stage of the process of writing a historical narrative. It enters when you do archival work and decide what's going to be in the archive for historians to find. It happens when you encounter the documents and bring your own suppositions. And then, of course, once you stitch together these fragments and create a story, you actually have to shave away alternative narratives and approaches. There's a way in which we assume that the story will make itself evident just by virtue of what's in the documents, but the story was already there in our own minds when we came to the material and made selections about what we were going to include and not include.

That's where I think the responsibility of the scholar steps front and center. You have to really be aware of what interests are advanced and furthered and what interests are hindered by the choices you make as a scholar, remembering always that you can't really achieve complete objectivity. We're human beings, we all have our own sense of our own past, and I think it's a false sense of security to think we're achieving objectivity through a distance from the archive. What we can achieve is accuracy. You can tell the most accurate story possible through rigorous engagement with the sources, taking in alternative voices, balancing various accounts, what they call triangulating—considering different takes on a given event. That's how you get to a more accurate story.

That makes it really incumbent on the professional historian to understand his or her own subjectivity in approaching the documentary evidence.

Absolutely. The way in which you, as an intellectual, develop through K-to-12 education, through stories told around the dinner table, through schoolyard conversations, and through professional narratives, all of that is going to go into the soup when you're writing historical work. In some ways, being very intentional in your choices is the best you can hope for. There are a lot of ways in which we make selections and we're unaware of why we're making those choices, or placing certain emphases on, for example, the utterances of presidents versus the janitors working in the White House. But if I'm clear that what I'm after is, say, the way in which Franklin Roosevelt developed the policy of the New Deal with an eye toward workers in the White House, that's a very different kind of approach. All historians are engaged in some kind of analysis about what they're going to include, but not everybody who makes those choices is fully aware of why they're making them.

Click to read the full transcript of the podcast

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged history, nathan connolly