Either pigs can fly or Karen "Kari" Meidenbauer's two mini pot-bellied pigs are escape artists worthy of a Las Vegas residency. In just under a half hour, the pair—one dubbed the Snotorious P.I.G. and the other Pringle—have both managed to crawl under a presumably sturdy fence to scrounge for worms in the neighboring field. Like a mother watching a toddler shed the cute yellow dress grandma bought, Meidenbauer laughs and shakes her head. "They have just been rebels ever since I got back from the honeymoon," she says. "They've gone rogue."

While Meidenbauer marvels at the animals' ingenuity, she worries about their safety. For one, she lives under a major Canada geese flyway, a location that brings a steady carpet bombing of bird excrement, potentially carrying parasites, bacteria, and viruses, including avian flu. Pigs can act as "mixing pots" or petri dishes for such pathogens, she says, mutating a relatively harmless strain into something more potent—and then passing it on to other animals or humans. (Hence a need to separate species.) As owner of this five-acre Maryland farm and a part-time clinical veterinarian, Meidenbauer frets often about such scenarios and the well-being of both her human and animal family, a crew that includes the two pigs plus five goats, 11 chickens, and two dogs.

Video credit: Greg Rienzi and Dave Schmelick

Her concern spills over to her other day job as animal health analyst at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory. As APL's sole in-house veterinarian, Meidenbauer focuses on animal health surveillance and the risk factors of zoonotic diseases, which are an increasing public health threat. Monkeys and bats were discovered to be carriers of the deadly strain of Ebola that killed thousands of people between 2014 and 2016. The global spread of bird flu has increased the risk of a human outbreak. And in the United States, between September 2016 and August 2017, a virus transmitted from puppies in a chain of pet stores sent 39 people to hospitals across seven states.

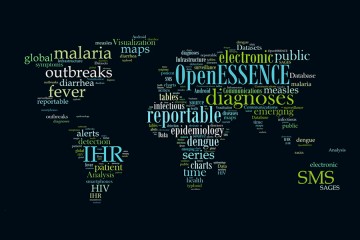

To mitigate and prevent such an outbreak, Meidenbauer says public health officials must identify an infected population early to stop further contagion. One potential aid in this effort is the APL-created Electronic Surveillance System for the Early Notification of Community-based Epidemics, or ESSENCE, a system developed in the late 1990s and first deployed after September 11, 2001, to look for signs of bioterrorism. Versions of ESSENCE have since been implemented by regional public health agencies across the United States.

Also see

ESSENCE, which gathers electronic data from clinical and nonclinical sources, can detect disease patterns and outbreaks in large populations. The system looks for anomalies and trends in emergency room data, records of urgent care centers, absenteeism from schools, sales of over-the-counter medicine, and other sources. Meidenbauer now wants to integrate animal data into the ESSENCE mix.

The main challenge is that animal health data tend to be gathered in silos—information only on dogs and only from one vet practice, for example—and not shared. One municipal health department Meidenbauer has worked with has started to compile data from that city's major animal hospitals to look for signs of specific zoonotic diseases such as leptospirosis. But this is the exception, not the norm. In particular, animal agriculture health data are currently not pulled into one centralized surveillance system.

Most major animal agricultural companies collect an immense amount of data on the health of their animal populations, she says. Before animals go to slaughter, a percentage gets pulled to be tested for avian influenza, salmonella, E. coli, and other zoonotic risks. Producers also regularly screen their animals and walk through herds and flocks every day looking for signs of illness. "Most do take detailed records, but what happens to all this data? Nothing, usually," says Meidenbauer, who joined APL in 2016 following an internship there. "They don't share the information. They don't need to."

The poultry industry has been reticent to make its animal health data available to third parties because of privacy concerns and a lack of trust with public health officials. But instead of finger-pointing at this industry for its production practices, Meidenbauer says a more inclusive approach is needed to help develop a mutually beneficial surveillance program. "I believe the poultry industry has good intentions," she says. "They work hard daily to raise healthy birds, and they certainly don't want people to get sick from their products. It's bad for business. And, their families and children are eating the same stuff."

She needs to prove to these companies the value of sharing data to spot health risks and emerging outbreaks. To date, Meidenbauer has met with several major poultry producers in the Delmarva Peninsula, and she recently spoke at the Delmarva Avian Influenza Joint Task Force annual meeting to discuss the overlap between zoonotic disease and worker health care. An animalborne illness could potentially cripple the industry and widely impact human health. A high pathogen strain of avian influenza could wipe out a flock of thousands of birds within 48 hours. And if USDA officials are not called in early enough to euthanize the birds, the farmers are not eligible for reimbursement from the federal government for lost property. "I tell the people I meet, share with us so we can help you," she says.

The more animal population health data streams we can monitor, the better the chance to catch an outbreak before lives will be lost, both humans and animals, Meidenbauer says. In a recent APL-led survey of Veterinary Medical Association members in Virginia, Maryland, and Washington, D.C., 75 percent said they had up-to-date electronic medical records in their practices, and another 10 percent said they had plans to switch to electronic medical records within the next year. Meidenbauer says these records would be invaluable if automated and monitored.

Ultimately, she foresees using existing surveillance platforms and technology to develop new integrated networks utilizing the "One Health" approach, referring to the global initiative that recognizes that the health of humans, animals, and ecosystems is interconnected.

For now, she'll have to work on reinforcing the fence around her pigpen.

Posted in Health, Science+Technology

Tagged applied physics laboratory, epidemiology, animals, population health