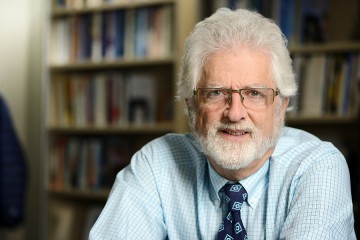

Katrina Bell McDonald kept noticing a striking statistic floating around and seemingly accepted as fact: Seventy percent of black women in America had never married. Turns out, the way that number was cited was misleading—it was from a 2009 Census Bureau report and pertained only to black women between ages 25 and 29; by age 55, the number of never-married women dropped to 13 percent. But McDonald, an associate professor of sociology at Johns Hopkins, felt like the widespread acceptance of the number came with an underlying assumption—there was something wrong with black women. The statistics didn't account for black men not getting married, she says, or reflect in any way all the black marriages that were working. "Social scientists weren't really talking about black marriage at all," McDonald says. "They were talking about black divorce or black nonmarriage."

Image credit: Alexandra Bowman

McDonald, herself married for 24 years, decided that there were enough studies on black people avoiding marriage or black marriages that didn't work. She wanted to show that married life is not a monolith, interviewing 60 couples—20 U.S.-born black, 14 Caribbean, 11 African, 15 white—for her new book Marriage in Black: The Pursuit of Married Life Among American-Born and Immigrant Blacks (Routledge, 2018), co-authored by Caitlin Cross-Barnet, an associate of the Johns Hopkins Population Center.

"Our motivation is not to say that [black] relationships are free of conflict but to say we see them as real people, with real lives, real commitments, and a desire for marriage," McDonald says. "What most people don't realize is even though African-Americans have low marriage rates in comparison to other groups, over the course of one's life, almost everyone gets married—everyone, across all racial groups."

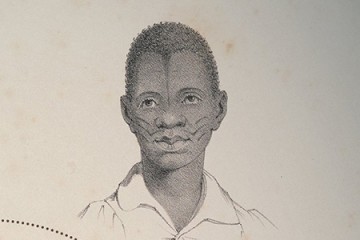

The book couples the qualitative research of the interviews with a historical look at black marriage, from slavery, when it was illegal for black people to marry, through Reconstruction, when it was encouraged by Freedmen's Bureau, established in 1865 by Congress to help former slaves and poor whites in the South with necessities after the Civil War. The agency helped blacks reunite with family members who had scattered during the war and urged them to assimilate by getting married. "They went door to door looking for couples that had been cohabitating and married them right on the front porch of their house," McDonald says. "A lot of blacks ran to get married after slavery; they were happy to have their relationships codified. Others weren't rushing to do it. A lot of it had to do with being free from slavery, period, and having the freedom to get married. Or not."

That theme of freedom extended to the co-authors' findings in their interviews. Marriage decisions among the American-born blacks they spoke with centered on love as the primary motivator. The white couples they spoke with were more likely to bring up the tradition of marriage before speaking of love. "They would say, 'This is how life is supposed to be done—you grow up, you go to school, you get married, you have children,'" McDonald says. "They have an order to how they do things. ... Blacks didn't say that in interviews."

Overall, McDonald says she hopes the book calls attention to the need or more rigorous study of black marriages. "People should pay more attention to the fact that there are more black married people in this country living normal lives, despite facing difficult circumstances," she says.

Posted in Politics+Society