Image caption: Rana Hogarth

Image credit: UI News Bureau

Medical historian Rana Hogarth, SPH '04 (MHS), wants to know how race enters the clinic. "One thing that currently drives my research is how ideas about race and difference get mapped onto people's bodies, and how that infiltrates day-to-day interactions even now with patients and their practitioners," she says. Think about it: Sickle cell anemia is still talked about as a black disease, even though we know that the gene variant for it is found in people of Middle Eastern, Indian, Mediterranean, and African descent. At some point, she notes, doctors began considering blackness "a medical thing, an entity that matters to clinical decision making in terms of how we diagnose and identify diseases."

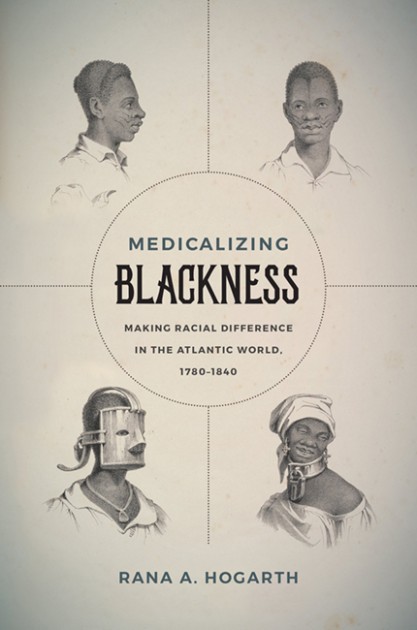

Hogarth's pursuit of those questions can be found in Medicalizing Blackness: Making Racial Difference in the Atlantic World, 1780–1840 (University of North Carolina Press), her recent debut book. Hogarth argues that blackness begins to become a clinical concept in the late 18th century in the English-speaking West Indies and the American South, and her book is an examination of how doctors began using blackness as an ostensible physiological and pathological fact in American medicine.

She's talking about medicine as an institution, not individual doctors. Medical historians, especially from the 1970s on, have shown how a number of 19th-century doctors passed off racist ideas about black bodies—their supposed susceptibility or resistance to certain illnesses, their capacity to work in the heat due to their African origins, etc.—as medical "facts" to defend slavery. This pro-slavery medicine, which appeared in medical journals and newspapers around the time of the Civil War, was written by then esteemed Southern doctors and shows how racism was politically interwoven into medicine in Southern slave states and colonial areas in the Caribbean.

Hogarth's research led her to see a narrative where, yes, racist medical ideas about blackness were used to justify slavery, but medicine advanced racist ideas about blackness far before that. "This profession benefited, institutions benefited, and doctors used this [perceived knowledge of blackness] for their own professional gain," Hogarth says. "Were they used to justify slavery and horribly predatory? Sure, but we know that already."

She found part of this narrative in the newspaper advertisements of the era, where late-18th-century doctors advertised the services offered at their slave hospitals. These ads provided context for understanding how physicians began to think about black bodies—slave bodies—in the early days of American medicine. Between 1791 and 1794, a Dr. Sheed of Charleston, South Carolina, ran newspaper advertisements in the City Gazette and Daily Advertiser announcing his "Hospital for the reception of sick negroes." At his slave hospital, Dr. Sheed offered his services in "physick, surgery, and midwifery" and described himself as "a gentleman in this city, highly respected for his medical abilities." In one ad, he boasted that since he first opened his practice "many have been relieved, who being distant from medical assistance must have fallen a sacrifice to their diseases—and that during the last fifteen months eight have been admitted, cured, and discharged, who had been given up as incurable."

By the mid-19th century, American medical schools, which had only recently started to appear in numbers, and their faculty would advertise in newspapers that they used the so-called "colored population" for instruction. Earlier doctors had advertised seeking black bodies as patients; a half-century on, teaching doctors saw black bodies as subjects used to train white medical students. In both instances, medicine sees the study, treatment, and use of black bodies as a way for career advancement, increased knowledge, and profit, independent of political motive.

And these medical issues about using race as a biological category aren't merely matters of archival nuance; medicine still contends with racial disparities in contemporary practice. "I'm interested in how health care disparities emerge, looking at different treatments and attitudes about treating people based on their race," Hogarth says. "That question started me on this path: How did race even enter medical discussions to begin with? That's always in the back of my mind, how the expectations that emerge from our definitions of race play out in terms of how we look at other people's bodies. I don't think that question is going to go away any time in the near future."

Posted in Health, Politics+Society

Tagged history of medicine, racism