A "look back" analysis of more than 600 major colorectal surgeries using a checklist tool adds to evidence that racial and socioeconomic disparities may occur during many specific stages of surgical care, particularly in pain management.

A report of the study's findings by researchers at Johns Hopkins Medicine, published last week in Diseases of the Colon & Rectum, documents the specific ways in which historically disadvantaged populations receive less optimal pain management and are placed on enhanced recovery protocols later than their wealthier and white counterparts.

"This study demonstrates that process measures, which guide and document each step of care, may be critical factors in preventing differences in care, particularly those due to race and socioeconomic status," says Ira Leeds, research fellow at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and the paper's co-first author. "We can't fix what we don't measure."

Enhanced recovery after surgery, or ERAS, protocols are predefined pathways designed to standardize some aspects of surgical care in order to reduce complications, decrease lengths of stay, and improve overall patient satisfaction.

To determine whether ERAS had an impact, or revealed any racial and socioeconomic disparities after surgery, Leeds and colleagues performed a retrospective analysis of information gathered before and after the implementation of a colorectal ERAS pathway at The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

A total of 639 patient experiences—199 pre-ERAS protocol implementation and 440 post-implementation—were used in the analysis of surgeries performed between Jan. 1, 2013 and June 30, 2016. The research team collected socioeconomic information, medical diagnoses in addition to colorectal disease, and surgical outcomes information housed in Johns Hopkins' National Surgical Quality Improvement Program's internal database.

Patients were categorized as either white or nonwhite, and low socioeconomic status or high socioeconomic status was determined by ZIP code. In all, 75.2 percent of the patients were white and 91.7 percent were categorized as having a high socioeconomic status.

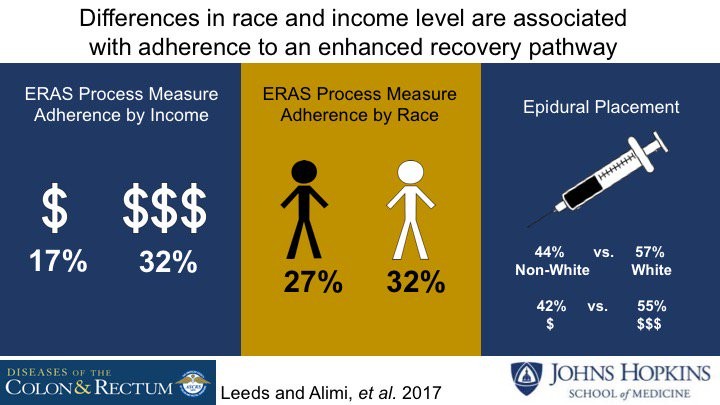

The researchers found that white patients were more likely to have transverse abdominis plane blocks or epidurals initiated and maintained than nonwhite patients. A similar trend for initiation of pain management was seen for high socioeconomic status patients. Leeds says this suggests that either nonwhite patients declined epidural blocks for pain management at higher rates due to inadequate counseling on the benefits, or that doctors carried implicit biases that led them to offer such pain management options less often to minorities and the poor.

Patients with a high socioeconomic status were placed on an ERAS pathway during scheduling more often than low socioeconomic status patients.

Leeds says the study results do not prove implicit racial or other bias as the cause of the differences in care, but they should, he says, heighten concern about the existence of such disparities and renew attention toward identifying and addressing bias.

While Leeds acknowledges the study's limitations of only including one institution and drawing from two datasets not designed to be merged for analysis, he notes that the findings add evidence regarding the efficacy of ERAS pathways in identifying disparities and highlight how short-term disparities can be mitigated by quality monitoring.

Read more from Hopkins MedicinePosted in Health

Tagged health disparities, surgery, pain management