Thirty-two pounds. That's how much a full bucket of tomatoes weighs when farmworkers pick them from fields in southern Florida. Thirty-two pounds, a little more than a cinder block. Pickers are paid per bucket, on average 40 cents. To earn roughly $50, a worker must pick about two tons of tomatoes—a day.

Greg Asbed has been trying to change this small sector of the agriculture industry over the past 25 years with the Coalition of Immokalee Workers, a human rights organization he co-founded that unites tomato pickers in southern Florida. In 2003, a Justice Department official told a New Yorker reporter that Florida's tomato industry was "ground zero for modern slavery." Workers live overstuffed in trailers. Women are sexually harassed. That 40-cent rate per bucket? Industry standard since 1978.

Since 2005, though, CIW has catalyzed profound changes in Florida's tomato fields. It secured workers a rate increase. It created a system to report abuse without fear of retaliation. It's bringing people who sexually assault women to justice and reforming a culture that permitted the assaults in the first place.

All this has happened because of CIW's Fair Food Program, which was developed by and for the workers in the fields. "We have a theory of change," Asbed, SAIS '90 (MA), told me about the program, "and it works." It works because CIW negotiates deals with the large corporate buyers who set the prices from tomato farms. Since 2005, the Fair Food Program has negotiated binding legal agreements with 14 fast-food and retail supermarket chains, from Burger King, McDonald's, and Taco Bell to Trader Joe's, Walmart, and Whole Foods.

One holdout has been Wendy's. If Wendy's wouldn't come to the table, then CIW would come to Wendy's. In March, workers traveled to New York to protest in front of the burger chain's corporate parent, the multibillion dollar asset management firm Trian Partners. For five days starting on a Sunday, more than 80 tomato pickers fasted in front of the midtown firm's building. For this Freedom Fast, people from local and regional peace organizations, faith-based communities, grassroots organizations, and labor unions joined the fasters in bracing 40-degree temperatures. They were also joined by college students who arrived by bus from campuses in Florida, Indiana, North Carolina, Ohio, and Massachusetts. As part of a protest march that marked the end of the fast, nearly 2,000 people blocked traffic as they crossed Second Avenue.

Image credit: Courtesy of Coalition of Immokalee Workers

Asbed was somewhere among this throng. Chatting with him you get the feeling he prefers organizing workers over public relations. Since being named a 2017 MacArthur Fellow last fall for the human rights work CIW is pioneering, he's had to adjust to being a bit more visible. And he's using those opportunities to amplify CIW's efforts—not just public actions, such as the Freedom Fast and its march, but the slow, 20-years-in-the-making consciousness-changing effort to create a model that gives the most marginalized and underserved workers in America some power to change their employment conditions.

They call this model Worker-Driven Social Responsibility, and it's being explored by dairy workers in Vermont and textile workers in Bangladesh. Its transformative power resides in how it activates all workers to know their rights and what to do when those rights are violated.

Asbed likes to think of the exploitative agriculture system as a big, ugly, disfigured piece of rock, and the Fair Food Program as a blueprint for Michelangelo's David. "What we did was make a million copies of that blueprint and gave it to every worker out there, along with a tiny chisel," he says. "Every time they see a violation of this blueprint, they're chipping it off. And through all these little efforts—all these workers, all these little chisels—we're creating a beautiful sculpture out of this industry that doesn't exist anywhere else."

Over the years, Asbed—who co-founded CIW in 1993 along with his wife, Laura Germino, SAIS '91 (MA), and farmworker and organizer Lucas Benitez—has developed a thought exercise he likes to use when talking to a group of people about farm work. Imagine driving through a rural part of the state and coming across a farm stand selling fruits and vegetables. You stop to get some. Now, what if while you were paying you saw, behind the stand, a farmer beating a worker or intimidating a woman, or a worker standing in 90-degree heat with no water or shade. Would you still buy that tomato? This scenario involves "a consumer buying something, but now how that thing is being produced is right in front of my eyes," Asbed says. "And I can't turn away from that. Now I'm hearing a scream while I'm buying. Does that change my mind?"

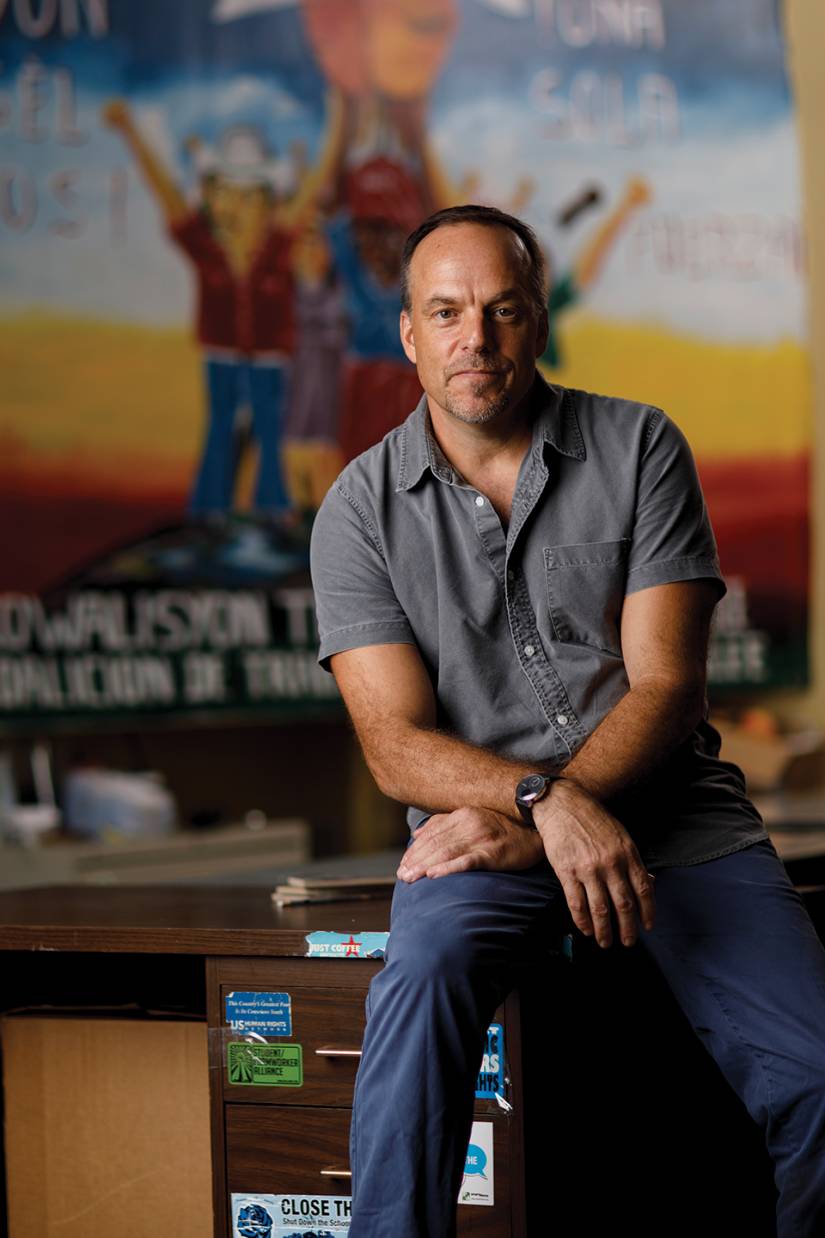

Image caption: Greg Asbed

Image credit: John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation—used with permission

Asbed didn't hear the scream until he was studying at SAIS. And to understand Asbed—what motivates him, what sustains him in the patient, incremental progress of human rights work—is to recognize that the scream is personal to him. Norig G. Asbed, Engr '61 (MSE), A&S '73 (MS), Asbed's father, was an Armenian immigrant to the United States. His father's mother survived the Armenian genocide; after most of her family was killed, she was sold to another Armenian family fleeing Turkey. Norig, who was born in what is now Syria, excelled in school, eventually becoming a student of nuclear physicist Niels Bohr in Denmark. Norig's graduate studies brought him to America, where he met Greg's mother, Ruth-Alice Davis, a pediatrician who was the chief of what was then the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health's maternal and child health clinic while Norig was in grad school. She would eventually work in public health for the state of Maryland and in the Philippines. Asbed's mother died in 1993, his father in 2015.

His family history's combination of perseverance and service inspired him to get involved in human rights work after he graduated from Brown University in 1985. He met Germino there, and they both wanted to pursue activist work (they would marry in 1993). The Peace Corps took Germino to West Africa while Asbed worked for democracy in Haiti. When they returned to the States, they figured they'd get graduate degrees and continue working in the developing world.

While Asbed was at SAIS, Germino worked with an organization providing legal aid to farmworkers in southern Pennsylvania. She had a case involving Haitians and brought in Asbed, who had learned to speak Creole in Haiti, to translate. "That was the first time that I learned firsthand about the conditions of farmworkers," he says. "That was the first time I heard the scream at the farm stand. And it was shocking."

He and Germino moved to southern Florida in 1991, and initially worked with Florida Rural Legal Services to get to know farmworkers in the community. Germino co-created CIW's Anti-Slavery Campaign in the mid-'90s, an effort that has investigated and assisted in the prosecution of farm slavery operations, earning national and international awards, including a 2015 Presidential Award for Extraordinary Efforts to Combat Trafficking in Persons. Immokalee, which rhymes with "broccoli," has been a major hub of tomato farming in the country for decades. It appears in Edward R. Murrow's sobering 1960 television documentary, Harvest of Shame, which reported on the inhumane working conditions of farm laborers. Workers then were mostly white and African-American. "We used to own our slaves," says an unseen farmer in Shame. "Now we just rent 'em."

Today, the majority of tomato pickers come from Latin America and the Caribbean. In fact, when Asbed started meeting with pickers in the early 1990s, a wave of Haitians was just arriving following the 1991 military coup that ousted President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. Among them were organizers Asbed knew. "We literally ran into each other on the streets of Immokalee," Asbed says. "People I worked with very closely, people who had the same uniquely powerful organizing and consciousness-building training that I got in Haiti. And suddenly they were there. And we were like, 'Damn, we have an opportunity here.'"

Video credit: James Beard Foundation

That opportunity was to unleash a process Asbed calls "conscientization"—developing a critical consciousness. What makes farmworkers poor? Why do they face so much abuse? What are the root causes of that abuse and what can be done to address them? CIW's founding motto is "Consciousness plus commitment equals change," Asbed says. "'Consciousness' comes first for a reason, the idea of understanding critically the situation you're in, why it is what it is, and what direction to go to address the root of that problem. From that comes the commitment to change it."

Asbed in conversation is thoughtful, often pausing to compose his next sentence. He becomes more enthusiastic and animated when talking about this process because he sees it as the foundation of what makes CIW and the Fair Food Program powerful: the community of people involved in both analyzing problems and brainstorming solutions. He's often referred to as one of, if not the, chief architect of the program, but he always redirects the discussion back to the role of the collective. This deflection isn't the superficial, there's-no-I-in-team thinking of business leadership; it's a fundamental insistence on creating an organization and system where everybody rises together.

The budding CIW started holding meetings, inviting any workers who wanted to learn about why they were poor and what to do about it. "We tried to do what workers have always done in order to exercise power," Asbed says. "If we withhold our labor, we can cause a disruption that brings our employers to the table. That's the fundamental idea."

They went on strike. They fasted. They occupied the town square where labor crew leaders load workers into buses to take them to farms. They marched. And nothing changed. "What we found out was that there's a certain level of poverty that is so deep that your ability to withhold your labor has a strict time limit because of things like rent and food," Asbed says. "If you don't have a safety net, you're living day by day already, so when you stop having money come in, you can only go about five days. And the farmers know that."

CIW's history in the 1990s was a string of large-scale actions that drew modest local press coverage but rarely any lasting results. "We had to take a step back and realize, OK, we've been fighting in Immokalee this whole time," Asbed says. "But the tomatoes that get picked in the fields don't stay in Immokalee. The food system doesn't stop at the growers because the food is consumed. We're connected to a bigger world. That's when we came out and said, 'Taco Bell makes farmworkers poor.'"

Gerardo Reyes Chavez started working in the fields when he was 11, first in Mexico, then in Florida, where he joined CIW in 2000. He's now one of its worker-leaders, and in March spoke numerous times to the protesters and fasters gathered outside Wendy's corporate headquarters during the Freedom Fast.

"The idea of the Fair Food Program started through the Taco Bell boycott," he said during a sidewalk interview in March. This boycott, launched in 2001, was a test to see if CIW farmworkers could get consumers to help them make corporations change how they do business. Taco Bell has more than 6,000 locations around the country and is owned by Yum Brands, the world's largest fast-food company. Many Taco Bells are located near high school and college campuses, making every student a potential ally.

Image credit: Courtesy of Coalition of Immokalee Workers

"We stopped in 17 different cities in 15 days on the Taco Bell boycott after several attempts at communication failed," Chavez says. "At the end of the boycott there were around 300 universities and some high schools in solidarity with the workers of Immokalee. Pretty much every major denomination got on board and endorsed the boycott." When Yum Brands finally agreed to meet the boycott's demands and talk with CIW, the resulting binding legal agreement laid the groundwork for a new way of negotiating worker-employer relations.

During the 1980s and 1990s, the American supermarket industry underwent radical change. Local and regional chains were bought up by larger ones. Warehouse clubs and discount stores also entered the grocery business. Walmart opened its first combined retail and grocery superstore in 1988; it was the largest food retailer in the country a decade later. In 2017, the top six food retailers—Walmart, Kroger, Albertsons/Safeway, Ahold (Giant, Stop & Shop), Publix, and H-E-B—accounted for more than 50 percent of all groceries bought in the country, with Walmart alone accounting for 26 percent. Together with fast-food chains—Taco Bell buys more than 10 million pounds of tomatoes a year—they possess gigantic purchasing power. They buy fruits and vegetables through corporate supply chains that buy from growers.

When only a handful of billion dollar corporations purchase a product in such vast quantities, they can effectively set prices, and everybody below them—trucking companies that deliver produce, farms that hire the crew leaders who hire the workers—has to push down labor costs to maintain a profit. While some costs have increased over the past 30 years, tomato pickers' rates have remained fundamentally unchanged since 1978.

Corporations, like consumers, don't think about the people picking their tomatoes, but they care about their brands. "Once we connected the very bottom of the supply chain to the very top, and created a voice of consumers telling corporations 'we don't want you to do business this way,' corporations responded," Asbed says. "It just took us a while to get there."

For Taco Bell, Yum agreed to pay one extra penny per pound of tomatoes. That additional money would be passed on to the workers as a bonus. Yum also agreed to adhere to a code of conduct, written by the farmworkers, that would be monitored and enforced by CIW. It's a simple and direct document that put market pressure on growers who wanted to sell their tomatoes to Taco Bell: Abide by CIW's code of conduct and agree to CIW monitoring, or Taco Bell won't buy your tomatoes.

In 2007, Yum Brands expanded the agreement to all its restaurant chains, which include KFC, Pizza Hut, and WingStreet. Since then, CIW has reached agreements with 13 other large retail food and food service buyers: Ahold, Aramark, Bon Appe?tit Management Company, Burger King, Chipotle Mexican Grill, Compass Group, the Fresh Market, McDonald's, Sodexo, Subway, Trader Joe's, Walmart, and Whole Foods Market. Through their supply chains, tomato farms in Georgia, Maryland, North and South Carolina, New Jersey, and Virginia are part of the program. Some strawberry and green pepper farms have joined the program, too.

The agreement inverts the dynamics between worker and grower. Chavez told me that farmworkers used to be scared to speak up about abuse. There were never consequences for abusers, who would either deny it, physically intimidate workers, or simply not hire them again. "You would have to ask yourself this basic question, 'Do I complain, knowing that I am not going to be able to put food on the table for my family?'" Chavez says. "That was a question that every worker would have to go through. With the Fair Food Program, that's flipped. Now the tomato industry has to ask themselves the question: Do I, as a grower, choose to defend and protect this crew leader, supervisor, or whoever is committing abuse on my farm knowing that if I do, I'm going to lose the business of the 14 corporations in the program?"

By 2011, 90 percent of tomato production in Florida, which accounts for the majority of tomatoes in the country between November and May, was operating under the Fair Food Program. CIW created the Fair Food Standards Council as a stand-alone organization to monitor and enforce the program. That meant that over the course of the season, the council's investigators, five at the time, would interview 50 percent of the more than 30,000 workers to audit how the farms were doing. And when the council officially opened, a 24-hour hotline went live for workers to report abuse.

The council received its first call inside of two weeks. Well, the worker meant to call the council's hotline, but he accidentally called a number for the growers instead and reported a violation. The grower was informed of the call, found the caller, and fired him in front of everybody. The fired worker eventually reached the council's hotline. "We went out that same afternoon, talked to all the witnesses, interviewed the crew leader and the grower," says Judge Laura Safer Espinoza, the executive director of the council. She served 20 years as a New York State Acting Supreme Court justice in New York and Bronx counties, retiring with her husband to south Florida. She contacted CIW saying she might be able to volunteer a few hours a week with the organization; Asbed, Germino, and other CIW members convinced her that her legal career prepared her to run the program's oversight process. "Within a couple of days, that grower was out there apologizing in front of the entire workforce to that worker, inviting him back with back wages for the days he was fired, and assuring everybody that nothing like that would ever happen again," she said. "The reason that nothing like that ever happened again is the serious market consequences for non-compliance. And when you see workers' faces as their boss stands out there and apologizes and they realize that a worker organization actually achieved the power to free them from retaliation, that's dramatic evidence of a tremendous culture shift in the workplace."

Implementing the Fair Food Program required drastic changes in how the growers operated. Workers wanted to be paid as direct hires, meaning each worker received a check for their work instead of the grower cutting a single check to a crew leader, who then doled out money as he saw fit. Workers demanded the right to shade and water while in the fields, basic amenities that aren't required by federal labor laws. The growers abided. "I get up every day and I'm astounded by this model," Espinoza says. "The market consequence, what Greg calls the power of the purchasing order, is profound. Beginning in the mid-1990s, almost every year some crew leader would get prosecuted for modern day slavery and sometimes go to jail, but the growers' operation was never affected. Since we started, there's been only one case, which would have been prevented had the grower not hired a supervisor flagged by [the council] as ineligible to work on participating farms. So the goal is not just to find the abusers and root them out but rather to make sure abuses don't happen to workers at all, and the program is doing an excellent job of prevention."

The code of conduct's stance on sexual harassment is a notable example. Women make up about 10 percent of tomato pickers, and "the standard set by workers is zero tolerance for sexual harassment with physical contact," Espinoza says. "So it's not like the penal law where it has to be sexual assault, the touching of an intimate body part, or even attempted rape. It's any kind of unwanted physical contact. The workers felt that was necessary because women were being groped with complete impunity since supervisors had that kind of power. Now any supervisor who sexually harasses a worker with physical contact is banned from working at a Fair Food farm for two years. A second offense is a lifetime ban."

THIS MORNING: The @FairFoodProgram education team hosted "Know Your Rights" sessions with hundreds of farmworkers, breaking out brand-new popular education drawings, covering the right to speak up without fear of retaliation and the right to a safe work environment. pic.twitter.com/4Ul1KEwev7

— CIW (@ciw) August 1, 2018

Fair Food Program monitoring enables CIW to track how the program is working. As of April 2018, the program had resulted in the tomato corporate buyers paying $26 million back to workers through the penny-per-pound mandate. Since its 24-hour hotline went live in November 2011, the council has received 1,800 complaints, 53 percent of which have been resolved within two weeks, 79 percent within a month. There have been nine cases of sexual harassment since the council was created; all the offenders were terminated.

What makes the Worker-Driven Social Responsibility model so effective is its universality and equity, says Cathy Albisa, a human rights activist, lawyer, and executive director of the National Economic and Social Rights Initiative in New York. The Initiative houses and advises the Worker-Driven Social Responsibility Network, which was created in 2015 to promote the model in other supply chains around the country and world. The Fair Food Program, for instance, "works for every worker in the sector," Albisa says. "It's not only available if you're a member of CIW, you're automatically entitled to these rights if the program covers your workplace. And it centers those who are most vulnerable, those who have the greatest needs."

How workers identify who is most vulnerable and what their needs are—the critical consciousness Asbed talked about—is the crucial part of the model. "Workers themselves identifying what they need to live a dignified life and have decent work is one of the most important step," Albisa says. "There's a process of identifying and analyzing the problem with as much clarity as possible. And every sector is going to be different."

For dairy workers in Vermont, an important issue was sleep. Cows get milked twice, sometimes three times, a day, which meant that workers were on split shifts, "where you punch in, work for four hours, punch out, sleep for three to four hours, wake up and punch back in," says Will Lambek, an organizer and activist with Vermont-based Migrant Justice, an organization that sought guidance from CIW. "And you're doing this around the clock. That makes what is an inherently dangerous industry that much more dangerous if workers are getting little to no sleep." When Migrant Justice created its Milk with Dignity campaign in 2014, one of its worker demands was the right to a single eight-hour stretch of sleep per every 24-hour period.

Milk with Dignity signed its first agreement with Ben & Jerry's in October 2017, and the program is now operating at 72 farms in Vermont and New York and covering 250 workers, who began seeing changes in their workplaces this year. Farmers started providing face masks, eye protection, and gloves. Workers started seeing a raise in their rates.

Over the summer, Asbed and some other CIW members visited a few farms to see how the Milk with Dignity program was faring. Workers showed them around, describing the improvements they've seen to both their housing and working conditions. Even one of the dairy farmers saw the benefit of the process; he told Asbed that when workers feel like they're being respected, they treat the cows with respect, and the cows make better milk.

Seeing a completely different set of farm workers use ideas developed by tomato pickers to bring changes to their own industry left Asbed practically giddy. "It's one thing to have the opportunity to see your theory of change work beyond your wildest dreams," he says of the Fair Food Program. "Especially in this day, to know that in this tiny corner of this world you're making things better in ways you can see and measure? That's beautiful. But seeing that replicated somewhere else? Seeing the theory stretch to a whole other environment and work? When we left that dairy farm, I was high."

Wendy's has yet to see the benefit of improving working conditions in the fields. Representatives of Trian Partners refused to meet with CIW representatives during the Freedom Fast. CIW continued its #BoycottWendy's campaign after the fast. In June, CIW members showed up at Wendy's annual shareholders meeting in Ohio to ask the company to join the Fair Food Program. And CIW members returned to midtown Manhattan in July to ask Wendy's one more time.

It took five years to bring Taco Bell to the table, and that was before CIW had evidence of how the Fair Food Program was working. But talking about the program working involves doing something consumers don't do: thinking about the lives of the people who make the things we consume. CIW's creation and work overlap with the food reform movement that grew out of health and safety concerns about industrial farming. And while advocating local, organic, sustainable, pesticide-free food is nice, promoting farm-to-table eating does not address the labor conditions in which food is grown and harvested. Writing in The Nation in 2008, Fast Food Nation author Eric Schlosser asked: "Does it matter whether an heirloom tomato is local and organic if it was harvested with slave labor?" A better idea might be to think about eating from farmworker to table.

And in today's political climate, that can be tough for some people. The U.S. Department of Labor's National Agricultural Workers Survey estimates there are 2.5 million farmworkers in America, 68 percent of whom were born in Mexico, and 80 percent of whom identify as Hispanic. And people from Latin America have been demonized by an administration that is aggressively targeting immigrants, migrant workers included. "We have always framed our work as fundamental human rights," Asbed says. "And one of the things about agriculture is that it has never cared whether you're an immigrant, what color you are, nationality, anything. It's historically been an equal opportunity exploiter. It's always taken advantage of people who are vulnerable.

"So, yes, it is a very difficult time right now. But for the most vulnerable populations in this country, it's been darker than it is today without any kind of light at the end of the tunnel. So in our minds, it's always been a 90-degree uphill climb. We don't focus on the [political] climate. We focus on the next handhold."

Posted in Politics+Society

Tagged agriculture, human rights, workers rights