Chris Lebron's The Making of Black Lives Matter: A Brief History of an Idea is a readably compact feat of political history and theory, connecting contemporary activism with a larger narrative of black intellectual labor. Lebron—whose first book, The Color of Our Shame: Race and Justice in Our Time (2013) won the American Political Science Association Foundations of Political Theory First Book Prize—joined the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences faculty this summer, and the Johns Hopkins Magazine caught up with him to talk about teaching philosophy via a social movement, radical art, and James Baldwin's idea of love.

In the book you put the activist/social media #BlackLivesMatter movement in conversation with a deeper reservoir of black political thought stretching back to the middle of the 19th century. Why is it important to explore the broader context of a contemporary political movement? What might we lose by not understanding that larger conversation?

Image caption: Chris Lebron

The desire to tap into the broader intellectual tradition was in part motivated by my concern that sometimes social movements, especially ones grounded in social media phenomena, can fizzle as quickly as they gained notoriety. To the extent that I could reach a broader audience, I wanted to make a contribution to the longevity of BLM by slowing down the conversation, so to speak. Additionally, probably no one believes that BLM is a spontaneous development in a new problem. Yet, more people probably are unfamiliar with the historical depths of the ethical claims embedded in the movement for black lives, so as an intellectual, I wanted to present a guiding framework. When we say, "black lives matter" we also mean, as Ida B. Wells meant, that the media cannot be complicit in the misrepresentation of black humanity.

In the section of the book where you discuss Frederick Douglass and Ida B. Wells, you mention that a recurring theme in the book is how blacks should "think of forgiveness and forbearance toward American institutions and whites." Was that a recurring theme you knew was going to be part of the book's discussions when you began it?

I can't say I knew it would be a recurring theme in the book, but I can say it's a recurring theme in my work and thinking so it's not surprising it emerged in the book. I am very much preoccupied with the push and pull of wanting to love America on the one hand, and the rational resentment toward the disdain American society and institutions often express towards black and brown folks, sometimes to murderous effect.

In the book you link a televised Kendrick Lamar performance to the work of Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston during the Harlem Renaissance. How can art be radical, as you explore it in the book?

One way of thinking about politics and sociology are as mediums for popular imagination. I mean that very crudely. Politics is in part a way of expressing a society's disposition toward the theme or debate of the moment. When we talk about race and its centuries-old status in America, we are in fact talking about a problem rooted in murder, rape, exploitation, and dehumanization, all of which is underwritten by gross hypocrisy. Hypocrisy is a state of mind wherein one holds one's belief about what is right and wrong, for example, but then either exempts oneself from what follows from that belief or simply thinks they are not complicit in the wrong.

Art, now, is a way of reaching beyond what theorists call deliberative rationality into the imagination. In the imagination we collect our memories, beliefs, hopes, and fears and do something new with those things. But in a society where personal safety is not a fear for some in the way it is for blacks, the very notion of what is dangerous cannot come into view for many white Americans. Art can help upset whites' sense of reality through work on the imagination. And rewriting someone's sense of reality is quite radical.

Could you talk a bit about discussing Audre Lorde alongside Anna Julia Cooper? I ask because, and here me not being an academic may be most apparent, I don't see Cooper's feminism put in conversation with contemporary politics all that often. What drew you to want to discuss Cooper, Lorde, and #BLM?

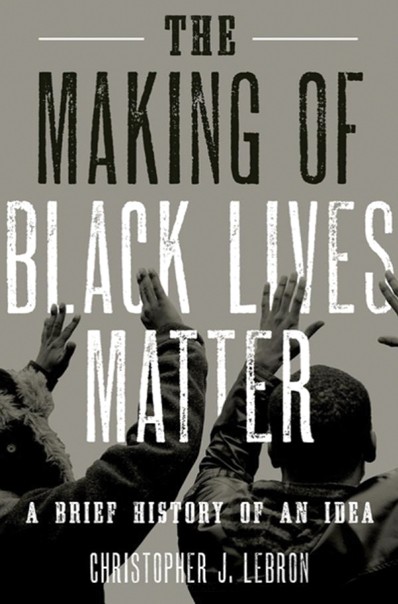

Image credit: Oxford University Press

I think it's fair to begin with the observation that very few black women intellectuals and culture producers at all are discussed alongside contemporary politics. That said, it is true that Cooper is especially less visible. That by itself was one reason. But with respect to Lorde, I hoped to show the range of black feminism that populates the history of black thought and in some ways add even more strength to Lorde's position by showing that she takes the same concerns as Cooper and makes them breathtakingly broad and even more humanistic by being an early theorist of intersectionality. In this way, Cooper acts as both predecessor and crucial point of departure.

I wanted to ask you about your use of love, as defined by Baldwin in The Fire Next Time. Why do you think more political philosophy doesn't engage with this idea that Baldwin so cleanly defines in terms of being the "tough and universal sense of quest and daring and growth"?

Great question. Love is a tough sell when we are talking about addressing asymmetric systems of power that can produce such heinous outcomes. Another reason has to do with the reason Baldwin isn't taken up in political philosophy more generally and that is he is not a systematic theorist in the way people in the field like to see, such as in someone like John Rawls. Baldwin didn't even consider himself a theorist. But as a person who remained true to the art of writing as a means of exploring and expressing the nature of ethics—and in his case, the ethics of democracy under racial oppression—Baldwin is most certainly a philosopher. But then that introduces another kind of complication. There is such little racial diversity in political theory and political philosophy so there is a question as to how Baldwin, much less his idea of love, can make it to the table. And in this Baldwin is not alone. Charles Mills is a living legend of political philosophy and yet many people I have encountered have never read him and he is a systematic philosopher. So now imagine the writing of a black man who at once excoriates whites for their ignorance while imploring blacks to love whites in order to assist with the project of America's redemption. Standard philosophical training does not prepare many people for that kind of an encounter.

Toward the book's end you put the larger argument you've made in conversation with a few conservative black critics. Was responding to these figures—Thomas Sowell, Randall Kennedy, Glenn Loury, John McWorter—something in the back of your mind as you were researching and writing?

The original plan for that chapter was to actually show how activists like Al Sharpton have abandoned the ethical ideals of the thinkers I do discuss. But then there was a mismatch. As you know, the book isn't really about the movement in its tactics and strategy. So, if I had discussed Sharpton and Jesse Jackson as movement leaders, there would have been a tonal mismatch. So I thought about different ways to illuminate how black ethical thinking can be derailed, especially when some of its luminaries internalize and propagate fairly ridiculous views that are all too familiar to both white conservatives as well as liberals. With the exception of Kennedy, who is the only serious and honest thinker in the bunch, this is a group whose views are not only wrong but detrimental to black well-being.

In an interview you did with the Yale Daily News I saw that you taught a course about the book. How did that go?

That course was highly rewarding. My main concern going into it was that students were going to take it thinking I was going to teach them all about the movement and personal strategies for protest. Again, that's not what my book is about. So I was honest about that the first day of class expecting to lose half the enrollment. But that's not what happened and it turned out the students were deeply responsive to thinking about the current movement and moment through an intellectual-historical spectrum. I was grateful for the seriousness they brought to the engagements.

Where has researching and writing this book taken you in terms of your scholarship? What are you working on now?

I've begun to develop a much longer and bigger book: an overlapping and interconnecting three-way socio-intellectual biography of James Baldwin, Audre Lorde, and Malcolm X. I have a very ambitious vision for the book.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion

Tagged book reviews, q+a