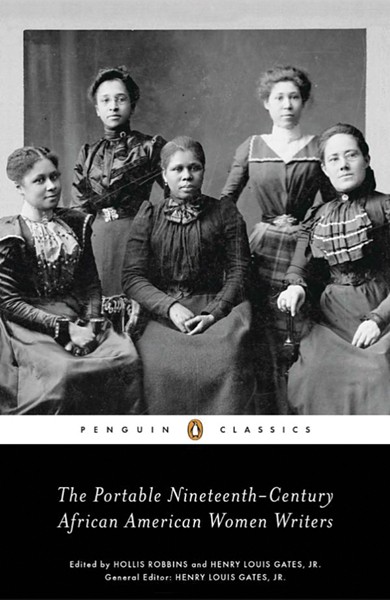

Though being on the faculty at both the Peabody Institute humanities department and the Johns Hopkins Center for Africana Studies keeps Hollis Robbins pretty busy, over the past seven years she still found time to research and prepare The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers, which she co-edited with Henry Louis "Skip" Gates Jr., the director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University.

Image caption: Hollis Robbins

Johns Hopkins Magazine caught up with Robbins, A&S '83, to talk about the collective effort to locate texts almost lost to time, the sonnet form, and all the things that 19th-century African-American women have to teach Alexis de Tocqueville about America.

This is the fifth book exploring 19th-century African-American literature that you've edited or co-edited. What drew you into this area of scholarly pursuit?

I didn't expect to become an expert in 19th-century African-American literature. At Princeton, my doctoral dissertation was on 19th-century canonical British and American works by Wordsworth, Dickens, and Hawthorne. But in fact, African-American writers in the 19th century were reading Dickens and Wordsworth, so my education was an ideal foundation for my later work. My expertise is in how black writers such as Frederick Douglass, William Wells Brown, Hannah Crafts, Harriet Wilson, Frances Harper, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Charles Chesnutt, and others engaged with and signified upon canonical British and American literature to create something entirely new. Without a substantial foundation in British literature it can be difficult to see all the ways that black writers were innovating back in the 19th century. I was fortunate to meet Henry Louis Gates Jr. in 2002 and begin a collaboration with him that's still ongoing.

During my first pass through The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers, I was appalled by how many writers it contained that I didn't know about at all. How and when did you and your co-editor, Gates, realize there was a big, gaping hole in literary scholarship about 19th-century African-American women writers that needed to be filled?

Skip and I first started talking about this anthology with Penguin back in 2010, right after I finished the Penguin edition of Frances Harper's 1892 novel Iola Leroy. I started putting together lists of women I'd want to include, and we sent preliminary lists around to every scholar in the field asking for recommendations. The list just kept getting longer! I kept having to postpone the project—first in 2011 after I became chair of Humanities at Peabody, which ate up lots of my time, and then again in 2014 when I was asked to step in as interim director and then director of the Center for Africana Studies at the Krieger School. The upside of the delay was that we kept discovering and hearing about new texts and new writers. So don't feel too bad—we didn't know a number of them until a few years ago!

Image credit: Penguin Classics

Of the newly discovered works, the writings of Edmonia Goodelle Highgate were the most delightful to me, and for those, thanks are due to the scholar Eric Gardner, who found her letters in the archives of The Christian Recorder. She was a schoolteacher from Syracuse, New York, who decided to go south during the war to teach newly emancipated children. Highgate's voice is so confident, so fresh, you almost forget she's only 22 years old, writing in the war-torn South, just after the end of the Civil War. Listen to these lines, from her letter, "Neglected Opportunities," from 1866: "A real man or woman makes circumstances and controls them." "I hate a weak man or woman. I fling them from me as I do half-drowned, clinging cats." "I don't believe in world-saving—but I do believe in self-making." This is a woman who believed in her own strength, her own power.

Or listen to her complain about clothing in another letter, "On Horse Back—Saddle Dash, No. 1," also from 1866: "Oh, how independent one feels in the saddle! One thing, I can't imagine why one needs to wear such long riding skirts. They are so inconvenient when you have to ford streams or dash through briers. Oh, fashion, will no Emancipation Proclamation free us from thee!"

I had heard about but had never read Eliza Potter's amazing 1859 tell-all memoir, A Hairdresser's Experience in High Life, and we include a fun sample. We also include excerpts from Mary Ann Shadd Cary's Plea for Emigration, or, Notes of Canada West (1852), which I had not known before, which offers answers to question that are often asked about what happened to fugitive slaves and other emigrants to Canada. Where exactly did families settle and how did they find work? How were settlements governed? Details about property, money, schools, governance, etc., are presented clearly and straightforwardly to encourage African Americans to move north.

Portable contains a wide range of writing—poetry, journalism, fiction, memoir, essays, etc. I know this is a big, loaded question, but when reading through the writings to put this book together, were any of the issues, ideas, or themes raised and explored by women in the 19th century that felt entirely too prescient or contemporary to the world we live in now?

Absolutely! These 19th-century women were writing about the central issues of their time and ours: liberty, democracy, equality, citizenship, individualism, modernity, history, and national character.

You might notice that these issues are precisely what Alexis de Tocqueville was writing about in his great study, Democracy in America, in the 1830s. But Tocqueville famously never spoke to an African-American woman in writing his "systematic" evaluation of the American people. The perspective of black women is totally absent, yet his book remains a key work of American political philosophy, taught in courses all over the country every semester, I'm sure right now at Johns Hopkins. The women writers in our anthology demonstrate that they were just as interested in questions of equality, democracy, and upward mobility as he was and I'm quite serious when I say that every single time Democracy in America is taught, our anthology should be assigned alongside it. Tocqueville left a lot of blanks and these women more than fill them in.

By the time you started working on this book, were these texts and authors easily accessible to study?

Some of the writings we include are available online but much of it is not, and we've republished here works that have not been published in full in over a hundred years. One is a poem called "Afmerica," by a writer named Mary E. Ashe Lee, first published in Hampton Institute's Southern Workman in 1886, and never republished in its entirety since. It's a remarkable poem, insisting upon the central role of black women in the making of America, as if she's talking to Tocqueville directly. Here's a representative stanza:

And why should she be strange to-day?

Why called the problem of the age?

Not so when slavery held its sway,

And she was like a bird in cage.

She was a normal creature then,

And in her true allotted place?

Giving her life to fellow-men,

A proud and avaricious race.

But now, a child of liberty,

Of independent womanhood,

The world in wonder looks to see

If in her there is any good?

If this new child, Afmerica,

Can dwell in free Columbia.

We've done book readings in Baltimore, Durham, and Harvard Square, and this poem is always a hit with the audience when it's read aloud.

Because I teach at Peabody, I was naturally interested in Ella Sheppard's memoir of her experiences as a pianist with the Fisk Jubilee Singers, which was first published in 1911. Sheppard tells stories of the group singing before royalty in Europe and harrowing tales of being threatened by rowdy drunkards on election night in an isolated train station in the woods. It's a wonderful memoir.

Are there are any writers in the book that you especially hope will be of interest to current undergraduate and graduate students that may kick-start new scholarship? Or, put another way, what is needed or lacking in the current state of scholarship about African-American women writers of the 19th century—or 19th-century African-American literature in general?

Right in the middle of our selecting poems, Frances Harper's long-lost first book of poems, Forest Leaves, turned up. Two years ago a young scholar Johanna Ortner went into the files in the Maryland Historical Society right here in Baltimore and typed the title into the catalog. Lo and behold, there it was—the society librarian brought it to her in an envelope. Forest Leaves—Frances Harper's first book of poetry, published sometime between 1846 and 1853! I wish I had thought to do that.

We've included three of the newfound poems and included two versions of "Bible Defense of Slavery," the first from Forest Leaves and the second from her 1853 collection, Poems of Miscellaneous Subjects, so students can get a glimpse of her revision process.

So yes, the field is wide open—there's very little scholarship on several of these writers and many of the texts. You'll see an excerpt from Sarah Farro's 1891 novel True Love, which was only rediscovered in 2015 by the scholar Gretchen Gerzina. You'll see writing by Jarena Lee, one of the first women to preach in the AME Church and the first African-American woman to have an autobiography published in the United States. We know very little about both of these women.

You're currently a fellow at the National Humanities Center in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina. What are you working on?

I'm spending my sabbatical year at the National Humanities Center finishing my book, Forms of Contention: The African American Sonnet Tradition. In the book I examine the long tradition of African-American sonnet writing, bringing to light many little-known poems from black press archives. I show how sonnets protesting race violence began to be appear in the black press continually from the 1890s through World War II. While they fell out of favor during the Black Arts movement, by the 21st century, black poets have now come to dominate the sonnet form, as the poetry of Rita Dove, Marilyn Nelson, Natasha Tretheway, Terrance Hayes, Carl Phillips, Elizabeth Alexander, Tracy K. Smith, and many others demonstrates.

Does your scholarly research and work influence your own poetry at all?

Sort of! I started writing sonnets in order to understand what it was about the sonnet that attracts poets to the form. They take a bit of work, but I understand the appeal. There's a rich history involved in sonnet writing and you feel like you are part of it. And you never have to worry about the shape of the poem you're writing. After 14 lines you just put down your pen and you're done.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion

Tagged africana studies