Kay Redfield Jamison says she began falling in love with the poet Robert Lowell in 1963 as a 17-year-old senior in high school, not long after her first debilitating episode of bipolar disorder. "My English teacher handed me a couple of his own books by Lowell and said, 'I think you might enjoy him.'" Lowell's poetry, says Jamison, "let me know that there was somebody out there who had contended with this awful force." She set about reading everything by a man who not only wrestled with mania and the exhaustion that follows but placed the battle dead center in his art.

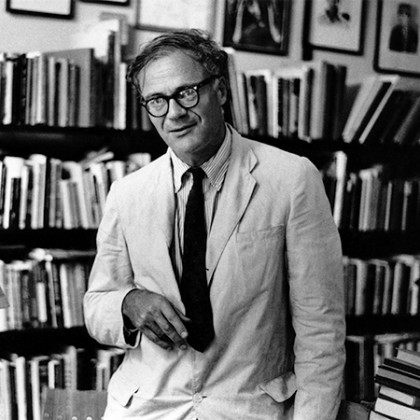

Image caption: Poet Robert Lowell’s battle with mental illness is the subject of Kay Redfield Jamison’s new book.

Image credit: Elsa Dorfman

Jamison's recently published Robert Lowell, Setting the River on Fire: A Study of Genius, Mania, and Character (Knopf, 2017), which coincides with the centennial of Lowell's birth earlier this year, is "a culmination of admiration for personal courage and love of great writing," she says. It's the seventh book for the School of Medicine professor of psychiatry, whose oeuvre includes the 1995 memoir An Unquiet Mind, which chronicles her own mood disorders, creativity, and suicide attempts. The new book is not so much the biography of a writer who, said fellow poet Randall Jarrell, "will be read as long as men remember English," as it is the history of an illness powerfully residing in one of the pre-eminent poets of the 20th century. This is a story of genius, genius derailed then heroically regained in the wake of multiple hospitalizations, electroshock therapy, psychoanalysis, alcohol abuse fueled by mania, and, as Jamison illustrates, an inner discipline worthy of the flintiest of Lowell's New England ancestors.

"Lowell approached life and his art with dead seriousness," Jamison says. And because of the cyclical nature of his mental illness—he'd been brought to his knees 16 times, he told a friend, getting up each time but fearing a 17th—he lived with the horror that one day he wouldn't be able to write. Yet something kept Lowell going, kept him faithful to the vocation he chose at about the same age Jamison was when she first encountered his work. "Such remarkable and difficult poetry, but poetry that moved and changed" as its author did, says Jamison. "People often talk about adversity. It's such a hollow word when you think about what Lowell went through over and over again."

Also see

Lowell was hospitalized a dozen times between the ages of 32 and 47, yet over the course of those years, he published the National Book Award–winning Life Studies (1959) and For the Union Dead (1964), the two cornerstones of his reputation. True to his sense of self-discipline, Lowell never fell into self-pity (though he did regret the wreckage his manic bouts left in their wake, including extramarital affairs with young women in the thrall of a literary superstar). His life improved greatly once he was prescribed lithium, a drug described in the book as having "certain modest magical qualities." But like many who suffer from mental illness, he wasn't always keen on taking his medicine. "He handled the illness with courage and class, and once he was well, he mended his fences as best he could," Jamison says. Most of his friends, including his ex-wives, the writers Jean Stafford and Elizabeth Hardwick, remained loyal to Lowell and did their best to separate the illness from the man.

Lowell died on September 12, 1977, from a heart attack in the back of a New York City taxi while on his way to see Hardwick, his second wife and the mother of their daughter, Harriet Winslow Lowell. Harriet proved to be an invaluable source for Jamison, providing access to her father's medical records, which Jamison's husband, Thomas Traill, a Hopkins professor of medicine and, by coincidence, a distant relative of Lowell's, reviewed and compiled as an appendix to the book.

"Lowell's life and work are a complex mixture of staggering imagination, darkness, and discipline," Jamison says. "I started writing this book with admiration and ended it in awe. He was a flawed and restless man of great genius and will." As for the author's own life battle with the illness, all is well. "It's under control and has been for a long time," she says. But she's learned to not underestimate the power the disease has over those who suffer from it. "You have to be humble before the disease."

Posted in Arts+Culture

Tagged mental health, kay redfield jamison