In September 1901, Theodore Roosevelt was vice president of the United States and speaking to an audience at the Minnesota State Fair. He said, "Let us further make it evident that we use no words which we are not prepared to back up with deeds, and that while our speech is always moderate, we are ready and willing to make it good." That is not the most famous line from that speech. This is: "Speak softly and carry a big stick—you will go far."

Eliot Cohen includes both quotes in the introduction to his book The Big Stick: The Limits of Soft Power and the Necessity of Military Force (Basic Books, 2017). Director of the Strategic Studies Program at the School of Advanced International Studies in Washington, Cohen describes himself as a military historian. He has taught at Johns Hopkins since 1990, and for 21 months starting in 2007 he was chief adviser to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice on Iraq, Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, and Russia. The Big Stick, Cohen's eighth book, is a thoughtful, carefully reasoned defense of the idea that American foreign policy requires, and will require into the foreseeable future, powerful armed forces that the nation must be willing to wield. He does not dismiss "soft power"—diplomacy, international agreements, alliances, treaties—but he argues that there can be no effective soft power without hard power behind it, and that the United States remains "the indispensable nation," in Madeleine Albright's phrase, for maintaining global order. American primacy is essential, he says, not just to the national interest but to global security, and there are serious challenges to that primacy that cannot be met without military strength. "Whether or not we end up using it, we'll find out," he says.

Military people speak of "sit reps"—situation reports. Cohen's global sit rep starts with China, which he considers a greater challenge than either radical Islamists or Russia. He believes China's emergence as a global economic and political power is the most significant development of the 21st century. "The challenge with China is that we have a very mixed relationship with them, both cooperative and conflictual," he says. "The Chinese don't have, I think, global hegemonic ambitions, but they have regional hegemonic ambitions and the desire to shape the international rules of the road to benefit them." The country has begun to throw its weight around in the South China Sea through territorial claims and an ever-larger navy, a situation that has rattled many of its neighbors.

Cohen's sit rep assesses three more security challenges: radical Islamists (he prefers the term "jihadis"); hostile states such as Russia, Iran, and North Korea; and what he calls "the ungoverned and the commons," by which he means outer space, the seas, the Arctic, cyberspace, and sections of the globe essentially ungoverned, such as Somalia, Syria, and Yemen. He does not mince words in regard to radical Islamists: The United States is at war with them. From the jihadi perspective it is a holy war and it will be a long battle. The former chief of staff of the Australian army, Peter Leahy, once warned that the West is now engaged in a hundred-year war with jihadis, and Cohen believes he may be right. "It's a mistake to think we can smash ISIS once and for all. I don't think we can. And if we did, other groups would metastasize and replace it."

Hostile authoritarian states like Russia, Iran, and North Korea pose challenges because all are threatened by liberal-democratic ideas, all have or want nuclear arsenals, and all have demonstrated a willingness to use force. The ruling regimes in all three are hostile to America and eager to assert regional power, and they foster deep grievances from recent history.

The challenges posed by ungoverned areas and the commons are less easily defined. But they include countering attempts at asserting dominance or control over sea lanes, Arctic resources (which are rapidly opening up as a result of melting sea ice), or space. A more obvious threat is aggression in cyberspace, with state-sponsored hacking (for example, Russian hacking of American political parties around the 2016 election) and disruption of digital infrastructure.

To respond to all these challenges, Cohen argues, the United States must remain a military power. He is not a warmonger. He's more of an order-monger. He points out that while there was plenty of bloody fighting during the 50 years of the Cold War, there was not another continent-spanning cataclysm on the order of the Second World War. He credits that sort of peace to regional defense alliances backed by sufficient military power to deter aggression, especially by the Soviet Union. Diplomacy, negotiation, and international cooperation in reducing conflict and settling disputes will always be the first choice, he says. But in Cohen's view, it's naive to think that bad actors and ambitious major powers can be contained or overcome by use of sanctions or diplomatic pressure alone.

"The subtitle of the book is 'the limits of soft power,' not 'the case against soft power,'" Cohen points out. He believes America's options are not binary, either all in for diplomatic solutions or all in for military force. Many situations require a combination of the two. He says, "In some ways, the greatest hard-power asset we have is the American alliance system, with allies all around the world and countries that are not allies but are effective partners. In those cases, military power and soft power are inextricably blended and it's a mistake to try to separate them out." There is the example of NATO, an alliance backed by several strong militaries and the commitment to regard aggression against one member state as aggression against all.

A different sort of example is India. It has never been a close U.S. ally in the same sense as Great Britain or Australia. But the U.S.-India defense relationship has been improving ever since the Clinton administration, Cohen says, and now represents an important counter to China. That's hard power, he says, but hard power that has grown out of the effective soft power of forging links with India. Cohen once spoke at India's naval war college in Goa, which then hosted him for dinner. "It was basically a bunch of admirals," he recalls. "Every one of them had either studied at the naval war college in the United States, had on some other occasion studied in the United States, had a son or daughter who was studying in the United States, or had other relatives living here. That makes [military cooperation] a lot easier, when there's this deep web of connections."

In The Big Stick, Cohen points to sanctions as a common but, he argues, ineffective soft-power tactic for countering belligerent nations like North Korea or Iraq. Not only is there much about the effect of sanctions that can hardly be considered soft—dictatorships have demonstrated on several occasions that they're willing and able to defy them. "The fact is, an authoritarian government is usually quite good at finding ways of offloading the pain of sanctions onto their populations," Cohen points out. "The Iraqi regime after the first Gulf war was under a pretty tough system of sanctions. I don't think that inflicted a whole lot of misery on Saddam Hussein, but it did inflict misery on the people of Iraq. No country's ever been sanctioned as much as North Korea, in an effort to keep it from getting nuclear weapons." And now North Korea has nuclear weapons. "My point is, understand that soft power often is only effective if it's married with hard power."

And the credible threat to use it. It is not enough, Cohen argues, to have potent hard power if your adversaries have reason to believe you will not employ it. He cites as an example what he feels was a mistake by President Barack Obama in dealing with the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria. Obama stated in 2012 that use of chemical weapons by the Syrian government against its opponents in the Syrian civil war would be a "red line," and crossing it would warrant U.S. military intervention. Less than a year later, al-Assad killed an estimated 1,500 Syrians in a poison gas attack and Obama did not order military strikes. In his book, Cohen argues that Russia noticed this inaction and it is no coincidence that Vladimir Putin soon used Russian military power in Ukraine to annex Crimea and back eastern Ukrainian separatists. Putin also ordered Russian military action in Syria on behalf of al-Assad.

Cohen warns that pulling back from military commitments could have other significant consequences. For example, China clearly aspires to regional hegemony in Southeast Asia and has been aggressive in asserting territorial rights in the South China Sea. North Korea continues to test missiles capable of delivering nuclear warheads and make bellicose statements aimed at the United States and South Korea. "If the United States said we're just going to be out of the military power game in Asia, the geopolitics of Asia would be transformed overnight," Cohen says. Alarmed allies would be forced to respond to the power vacuum. "We could end up with Japanese nuclear weapons and Australian nuclear weapons. We could end up with the Chinese deciding they have free rein to muscle Taiwan into submission. All kinds of things can and will happen—enabled by our absence."

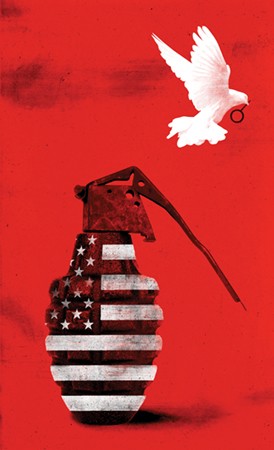

Image credit: Rob Dobi

In the opening section of The Big Stick, Cohen anticipates the principal arguments against the maintenance and use of military power. One is the cost. The United States has the largest defense budget in the world, by far. The Department of Defense states 2016 military spending as $580 billion. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute estimated in April 2017 that American military spending in 2016 actually amounted to $611 billion. Either figure represents more than half of all federal discretionary spending. Cohen doesn't deny that this is a lot of money, but he notes it represents only about 3 percent of gross domestic product, a figure significantly lower than in previous periods. During the Cold War, for example, the United States spent between 6 and 10 percent of GDP on defense. A massive military capable of projecting force anywhere in the world is indeed expensive, Cohen says, but the United States can afford it.

Cohen also takes on the argument that recent U.S. experience in several conflicts demonstrates that the United States is not all that competent when it goes to war. Thousands of lives and nearly $3 trillion expended in Iraq and Afghanistan have not resulted in the sort of conclusive outcome of, say, the Second World War. The United States used military force in Libya, a nation now in havoc. The critics' list goes on. Cohen responds that a useful evaluation of U.S. military effectiveness is much more complex and mixed. He points out that American armed forces were extraordinarily effective in defeating Saddam Hussein in the second Iraq invasion, halting Serbian aggression in Kosovo in 1999 (as part of a NATO bombing campaign), and assisting the Colombian military in successfully concluding the decades-long civil war in that country. That there have been notable military failures, he says, has to be accepted as a reality of international affairs that all nations experience. Statecraft and warfare alike are fraught endeavors that frequently produce ambiguous outcomes and unforeseen consequences.

At the heart of Cohen's book is an insistence on the need to be realistic. Standing up to China will be vital to U.S. interests and cannot be done without a robust military presence in the Asian Pacific. Russia has already offered ample proof that it is intent on breaking apart NATO and undeterred by the threat of international disapproval or sanctions. The war against radical Islam will not be short-term with a tidy outcome. The United States will need resolve to guard its security and maintain order in an unruly, well-armed world.

He is critical of American political leadership for not doing enough to maintain public resolve for the future he sees. "I bristle when people tell me that they're 'war-weary,'" he says. "The American public has not been asked to sacrifice at all. It's a very small minority of American young men and young women going into the armed forces. If you're a veteran, you're entitled to be war-weary. If it's your spouse or kid at risk, sure. If, God forbid, you've been wounded or you're dealing with a bereaved family—you are certainly entitled to be war-weary. But I don't think the rest of us are. And something I feel more and more strongly over time: American political leaders, across the political spectrum, have really failed our people in terms of making the case to them for why we're doing what we're doing, of simply explaining what we're doing. In my previous book, Supreme Command, one of the points I make is the importance of political rhetoric in wartime. I pointed to the great Churchill speeches of the Second World War. If you look at those speeches, what they are mainly about is Churchill explaining to people that this is where we are in the war, this is why it's worth fighting, this is how it's gone thus far. For a number of reasons, American political leaders either don't have those rhetorical skills anymore, or don't think that they need to have them and exercise them."

Cohen notes with a slight smile that "Johns Hopkins pays me very well to think about very dark things." But he ends The Big Stick with a restrained call for optimism: "Despite all of America's blunders and errors, the wars half won and the setbacks unredeemed, U.S. military power has, on the whole, been a force for good in the world. The use of that power was a critical element—hardly the only one, but indispensable—in winning the Cold War and securing unprecedented prosperity to ourselves and others. With good judgment and careful management, it will continue to be so. We cannot assume that the world of the 21st century will avoid horrors as bad as, or even worse than, those of the 20th. The better angels of human nature have not triumphed. But the record of the last century also teaches us that even in the darkest times, the proper temper of freedom remains sober optimism, and in that respect, nothing has changed."

Posted in Voices+Opinion, Politics+Society

Tagged foreign policy, eliot cohen, military, national security