Toxicologist Alan Goldberg knows what an industrial pig nursery should look and smell like. So one with no pigs, no slop, and no aroma was certainly surprising. Goldberg toured such a sanitized—and possibly staged—facility in 2006 while he was part of the 15-member Pew Commission on Industrial Farm Animal Production, tasked to examine how industry practices impact human health, animal welfare, the environment, and rural communities.

The facilities with actual animals in them told a different tale. He recalls one poultry shed in Arkansas that housed 45,000 chickens clustered on a dirt floor that had likely not been cleaned since before the last harvest. Inside, the potent mix of nitrous oxide and ammonia, a byproduct of the chicken feces and urine, made the commissioners' eyes burn. "The word the Pew Commission used to describe the conditions we saw was 'inhumane.' Personally, I would say 'cruel,'" says Goldberg, a professor of environmental health and engineering at the Bloomberg School of Public Health and the founding director of the school's Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing.

In its 2008 landmark report, the commission condemned the state of industrial production and made sweeping recommendations, including the ban of nontherapeutic anti?biotics, improved management of food animal waste to lessen contamination of waterways, and the phasing out of intensive animal confinement. The report received wide publicity, but in the eight intervening years little has changed. "The agricultural lobby is incredibly powerful, and the industry still largely unregulated," he says.

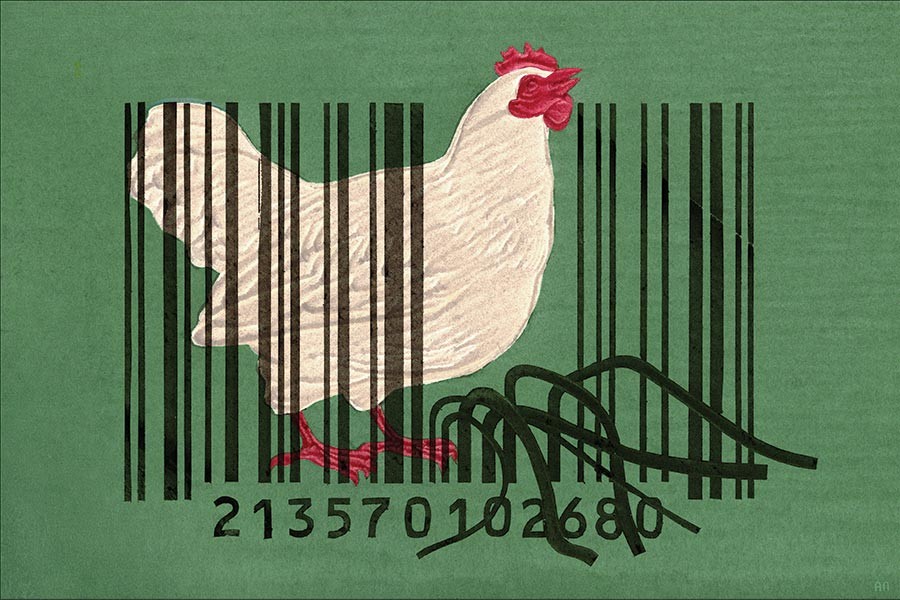

The slow progress drove Goldberg to look for other ways to influence industrial food production practices. One possible tactic: make the food that is ethically produced easier to identify, and let the consumer drive demand. He envisions a comprehensive ethical certification that would rate adherence to multiple criteria related to the environment, animal welfare, labor standards, water utilization and contamination, and food safety. The corresponding label could be a stylized "E" on the package, accompanied by a QR code that consumers can scan to see how the product scored in each category. The philosophy behind the label, which would be the first of its kind, is to create a template of ethical standards for the food industry and better inform consumers about their choices. Ethically produced food, after all, has become big business. The U.S organic food industry posted a record $43.3 billion in sales in 2015.

The project, funded by the Stavros Niarchos Foundation and launched in fall 2016, will first focus on finalizing a set of standards that can be adopted by the food industry. To do this, Goldberg assembled a group of faculty at the Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics and recruited an international academic team of seven non-JHU experts in animal rights, health policy, agriculture and food production, ecology, and law. The group will identify the necessary measures to achieve this ethical certification. The trick, he says, will be to make sure they don't overreach with standards that can't practically be met, or ones that don't have sufficient impact.

Ethical labels and the certification process are nothing new, but existing ones are highly specialized and typically focus on just one issue.

A quick scan of grocery store shelves verifies the ever-growing list: Certified Organic, Non-GMO, dolphin-safe, free-range, cage-free, Fair Trade, Animal Welfare Approved, American Grassfed, and so on. Many of these labels' standards are verified by a third-party audit and require annual renewal.

As part of the project, Goldberg and his team will appraise the standards and certification processes of these existing food labels to determine best practices and flaws in the system. The result will be an online ethical label database to share with industry and consumers. "Some [labels] are very good at what they do," he says. Others, he cautions, may not be accurate or say anything of value to the consumer.

Goldberg says the transition to more sustainable and humane food production will not necessarily require a significant cost. To go from battery-cage egg production—where hens live confined wing-to-wing in wire cages—to a facility that is still industrial but offers the chickens some freedom of movement increases the cost per egg at the retail level by roughly 1 cent, he says. He compares this relatively modest change to a turkey farmer switching from a factory farm system to pasture-raised birds that roam in open fields. "I don't expect every company to produce every food to the highest ethical standard. There are certainly associated costs and might not be advantages," he says. "But there are basic things we need to be concerned about, such as the overuse of pesticides, animal cruelty, and the utilization of water."

Ethical branding has already had a significant impact on the food industry. Goldberg points to the example of "free-range," a term that consumers increasingly look for when shopping for eggs. In the past two years, dozens of goliath companies including McDonald's, 7-Eleven, Dunkin' Donuts, Costco, Nestlé, and Target have committed to selling only free-range eggs by 2025. Goldberg says many of these same large companies could be early adopters of the label to woo the growing number of ethically conscious consumers.

But Johns Hopkins will not get into the business of certifying food. Goldberg says the university will likely license the intellectual property to an independent entity, which will act as the certification-granting body and perform annual audits to make sure the standards are being upheld.

Posted in Health, Politics+Society

Tagged ethics, industrial farms, food production