A Washington Post features reporter and novelist, Monica Hesse relocated to Accomack County on Virginia's Eastern Shore for a few months while researching the arsons that she covers in her new book, American Fire. Johns Hopkins Magazine caught up with Hesse to talk about reporting in rural America, combustible love, and how investigators get to know a fire after it has burned.

The serial arsons and arrests were covered by the Washington Post in the more conventional news manner during the investigation and arrests. What made you suspect there was something more to look into?

Image caption: Monica Hesse

As soon as Charlie and Tonya were arrested and their identities were revealed, I knew this was a big, strange, fascinating story. It's really uncommon for women to be arsonists, and I never found any examples of romantic couples lighting fires together. So, were they doing it because they had a vendetta against the county? Because they were trying to make a political statement? I went down to Accomack County for Charlie's arraignment and learned that the reason was more simple and more complicated than I ever would have guessed. They were doing it for love. It was a love story that became an arson story.

Did you have a good understanding of Accomack County's economic history when you started reporting? Because the backstory context you provide feels so necessary for understanding the county today.

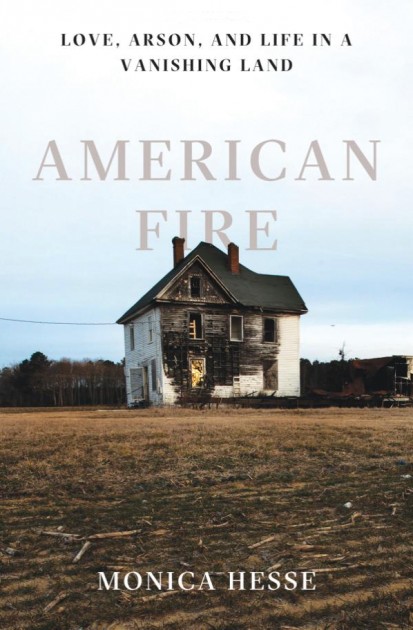

When I started reporting the story as a newspaper feature, one of the first things I did was contact a local historian to give me a sense of the place. So I did have a thumbnail-sized idea of Accomack and what it had meant through centuries: the fact that it had the oldest ongoing court records in the United States, the fact that it used to be one of the two richest rural counties in America but was now dotted with abandoned houses crumbling by the road. But there were other things about the county that I really couldn't understand until I moved there—like how, in downtown Tasley, older residents could remember walking to the general store to buy candy and clothes and dry goods, but that now, the only place to buy anything on Tasley Road is a Pepsi machine by the fire station. The county is dripping with ghosts of its own past.

I appreciate the residents of Accomack County separating their fellow citizens into those Born Here and those who merely Moved Here. Can you talk about being a Reporting Here?

The sheriff in Accomack is a beloved figure in the community. Everyone knows him and most everyone likes him. In the beginning, whenever I tried to talk to anyone, they would suspiciously say, "You better talk to Todd Godwin first." And man, was I trying to talk to Sheriff Godwin. I'd left him voicemails, emails, text messages, and I could not get him to respond—but without his response, I couldn't get anyone else to talk. Finally, one night I ran into him at the high school football game; his son was on the team. He told me to stop by his office the next day. That night, when I told my mom about the conversation, she said, "Be sure to bring him a pie."

My mom was talking literally, and I took her advice pretty literally, though I brought banana bread instead of pie. But it's also a good metaphor of how I think you have to come into stories like this. You can't waltz in with a notebook and expect people to trust you immediately. You have to show that you are deeply interested in your characters as people. That you want to get their stories right, and you will dedicate as much time as you need to in order to do that. The day that I brought the banana bread, I didn't bring my notebook. I just sat in the sheriff's office and listened to all the deputies tease each other, and tease me. I watched people wander in to sell raffle tickets, or share photos of the homecoming dance, and all of that taught me more about what it was like to live in Accomack than anything I could have learned in a formal interview.

In the time I stayed down there, I didn't write a single word. But I went to a lot of firehouse meetings, church potlucks, haunted houses, backyard cookouts, and town halls. I watched people fix their cars, I got up at 5 a.m. to make the farmer breakfast crowd at the Hardee's, I slept at the fire station again on a mildewed couch. The book absolutely would not have worked without the incredibly generous people of Accomack letting me observe these parts of their lives, and doing it was the only way I felt like I could write about a place with any credibility. If I was going to talk about how dark Rose Cottage Road got in the middle of the night, then I better have spent more than a few midnights driving down it myself.

I think journalists do a good job of writing about criminal investigations because there's a fair amount of overlap in the kinds of information synthesis going on in both. From reading American Fire, I get the impression that arson investigation can be a bit more elusive because, as you write, at these crime scenes a fair amount of evidence burns. Could you tell me a bit about wrapping your head around fire investigators, how you went about getting to understand what they do so you could write about it with such succinct authority?

Mostly I have to thank Bobby Bailey, an instructor with the Virginia Fire Marshall Academy, who was brought in to consult on the investigation. I'd asked if I could come interview him for an hour and ended up staying for six, learning about V patterns and soot lines and which materials burn faster or slower. Later he let me come to Richmond and sit in on a fire investigator certification class, so I could learn what would have been going through the minds of the Accomack investigators as they approached the scene of a fire. Of course, with the Accomack arsons, the investigators often didn't get to put their learning into practice: The buildings that burned were old and dry. By the time investigators reached the scenes, they were piles of ash with no clues left behind.

I get the impression you didn't get to interview Tonya Bundick as much as you would have liked. Aside from hearing more of her side of the story, what would you have liked to ask her about? What questions remained about her narrative, questions that she's going to be the only person able to answer? And I ask because she comes across as the kind of person who isn't going to open up simply because somebody's asking her to.

There were several things I learned about Tonya that I didn't put in the book because they ranged anywhere from "vague rumor" to "I believe this is probably true." I didn't include them in the book because it wouldn't have been responsible—and for the same reason, I won't repeat them here. But if I ever talked with her again, I'd probably say, "Just between you and me, no notebooks, no cameras, not for print and not for repeating: This is my theory of you. Is it right?" And it would purely be for my own curiosity. I'd never tell anyone what we talked about, or even that we'd talked.

Charlie Smith, on the other hand, comes across as somebody who could move from hello to candid after a few seconds of chat if he decided he liked you. Was the power of his relationship with Tonya evident when you covered the trial? Was he fairly forthcoming in talking about his feelings for her and their relationship? Because the intimacies of their relationship play a role in their story and the arson, and you're able to relate how strong, for good and ill, their bond was.

When Charlie and I first started talking, he was still in love with her. He would still get emotional mentioning the highs of their relationship, and he never refused to answer my questions, as personal and nosy as they eventually became. All of that is really wonderful for a storyteller but also dangerous because you never want to rely too much on one person's account of events. Luckily, their relationship didn't happen in a vacuum. They had friends and family who were able to tell me what Charlie and Tonya had been like together. They had a joint Facebook account that was publicly viewable and frozen in time. It was like an archaeological dig, except instead of excavating layers of pottery to find out what felled an ancient civilization, it was excavating a love affair that had turned terribly tragic.

Smith is currently serving 15 years, Bundick 17 1/2—that part of this story is over, but I am curious as to how these arsons changed the county and its residents.

There is not a person in Accomack County who cannot tell you, in detail, what life was like during the months of the arsons. It's like the assassination of JFK—a historic event that will define this county for an entire generation. The arsons were an intrusion of a big city crime wave into a small town way of life. They disrupted this beautiful bubble of safety. And then it turned out that the culprit was someone they'd known all along.

Did working on the book project after reporting the story for the Post provide you with any insights into how you might report long-form narratives in the future? Any moment of, 'Oh, next time I'm working on a sprawling story, be sure to think about this or ask about that?'

A book is really a singular experience. As much as I'd like to say that the lessons are applicable in my day job, the biggest lesson is that there aren't really any shortcuts for a big narrative project. I could not have written this story if I'd only spent a week in Accomack—or, more realistically, a day in Accomack, which is what a lucky reporter would have been given to write this story for a news organization. I will say that I did not expect to write a book about serial arsonists and have the arsonists come off as sympathetic figures by the end of my reporting. Maybe that's a useful lesson, not only for long-form narratives but for all writing: If a character seems all bad or all good, you probably don't understand them well enough yet.

Do you have any book projects you're currently working on that you can talk about?

The other half of my book-writing life is dedicated to fiction—I just turned in a manuscript for a YA novel set in a World War II internment camp. Completely different in tone and topic, but there's love and heartbreak in that novel too.

Can we expect to see the American Fire movie or television serial adaptation anytime soon? Because I can totally see this story being an ideal binge watch.

From your lips! Seriously, I have a contract sitting in front of me waiting to be signed as soon as I can get to a notary. I'm pretty stoked about it, but probably can't say anything else until the ink is dry.

Read Bret McCabe's review of American Fire.

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion

Tagged q+a