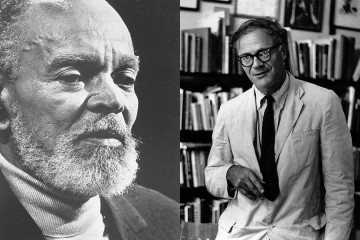

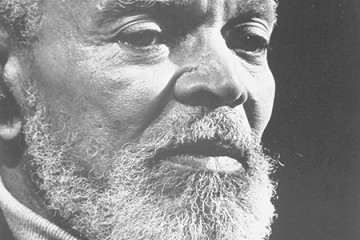

Chester Bomar Himes witnessed man's capacity for horror and heroism from his prison cell. He was 21 years old, serving the second year of a 20-year sentence for armed robbery, when around 5:30 on the evening of April 21, 1930, scaffolding surrounding part of the Ohio State Penitentiary in Columbus caught fire. The prison had been built in the 19th century to hold 1,500 inmates; by 1930, it was crammed with roughly 4,200 men. The scaffolding was part of renovations, and the construction site provided lumber, sawdust, tar, kerosene, and other accelerants. The blaze spread to the roofs of the prison's G and H blocks, each housing around 800 men who had been locked in for the night after evening meal. About a half-hour after the roofs caught fire, they collapsed. In all, 322 men were killed, 230 injured. It remains the deadliest prison fire in U.S. history.

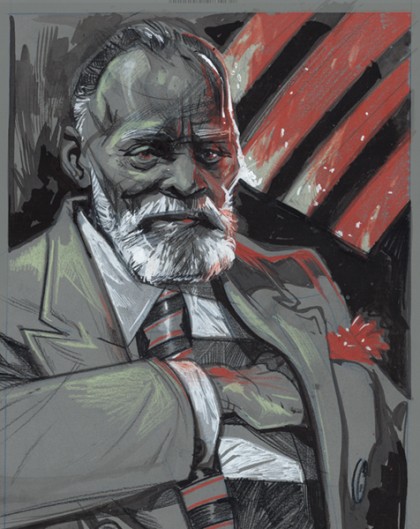

Image credit: Chris Visions

Over the next two days, Himes saw the bodies of dead men left in the yard during the initial cleanup. In the two weeks after the fire, the inmates refused to go back to their sentences' hard labor, protesting guards' initial refusal to release men from their cells when the fire started. These prisoners, segregated by race and capacity for violence, whom Himes had observed doing heinous things to each other before the fire, became the men trying to help each other when the guards didn't.

Himes, publishing with his prison number "59623" as a byline, captured these extremes in "To What Red Hell," the first short story he published in Esquire. A white prisoner watches the prison world burn: "The sights of convicts who were in for murder and rape and arson, who had shot down policemen in dark alleys, who had snatched pocket books and run, who had stolen automobiles and forged checks, who had mutilated women and carved their torsos into separate arms and legs and heads and packed them into trunks—now working overtime at their jobs of being heroes, moving through the smoke with reckless haste to save some other bastard's worthless life. White faces gleaming with sweat, streaked with soot; white teeth flashing in greasy black faces. All working like mad at being heroes, some laughing, some solemn, some hysterical—drunk from their momentary freedom, drunk from being brave for once in a cowardly life."

Though Himes had started writing before the fire, living through it ignited his ability to empathize with the sophisticated interior lives of men discarded to society's margins. Over the next few years, his polished, tight short stories started appearing in black magazines such as Abbott's Monthly and Atlanta Black Star, and eventually Esquire, the new magazine that was publishing articles and short fiction by Theodore Dreiser, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, and Langston Hughes.

Also see

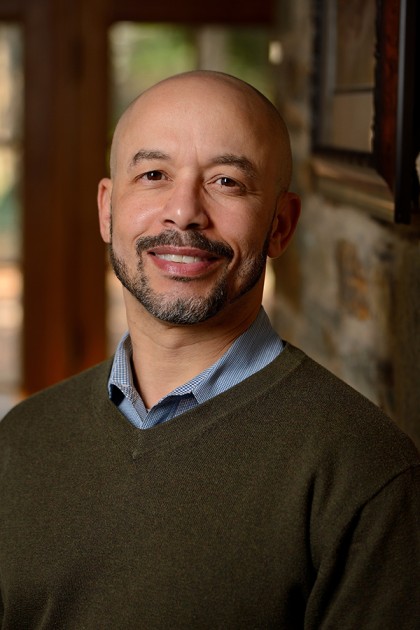

Himes' early characters were white, but he was already displaying a "really remarkable insight into the nature of this experience of confinement, sort of the longing for freedom on the edge of psychosis," says Lawrence Jackson, a Johns Hopkins Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of English and history and author of the recent book Chester B. Himes: A Biography (W. W. Norton). During the two-week period after the fire, "all of these social barriers break down. I think Himes approached something about the nature of human evil, not just with the death of 322 people but also having to share space with some of these other characters and trying to puzzle through what it meant to him, the relationships he was having and started to have afterward. This is really where the writing starts. You see him systematically working through a menagerie of grotesques."

At the time of Himes' parole in 1937, the possibility of being a black crime novelist didn't really exist. The crime- or prison-to-writer career path—see Robert Beck (better known as Iceberg Slim), Claude Brown, Eldridge Cleaver, K'wan Foye, Donald Goines, Nathan McCall, Malcolm X—didn't exist. (Sure, William Sydney Porter, aka O. Henry, started writing while doing time at the same Ohio State Penitentiary, but he was white.) Himes was doing what all writers must—drawing from his experiences—and, as for all writers, the process performed the emotional labor a writer needs.

And as Jackson argues in his biography, Himes wanted to come across as tougher than he felt, and the fiction did that work. Himes did his time in the "cripple" dormitory for men with physical disabilities, which freed him from shoveling coal and afforded time to write. Four years before going to prison, Himes, the youngest child of a middle-class black couple, plummeted two stories down an elevator shaft at the Cleveland hotel where he worked as a busboy. His jaw shattered, teeth cracked. He broke his left arm and fractured two vertebrae. Though a workman's compensation claim covered his hospital bills and provided a modest $70 monthly income, he was in a body cast for four months. He relearned to walk while wearing a leather and steel back brace that his mother had to help him secure at his groin. A lean teen before the fall, Himes at 17 was a slight, limping young man with a broken smile in a scarred face.

He entered Ohio State University but lasted only a year. Self-managing pain with booze and drugs led to hanging out with people from the wrong side of the class tracks, which eventually led to crime. He worked Cleveland's black gambling dens. He stole cars and cashed fraudulent checks, which landed him a few months' stay in jail. When he got out, he and some mates robbed a National Guard armory. That score gave him enough false bravado to rob a well-to-do Cleveland family at their home. After he tried to fence jewelry at a pawn shop in Chicago, he was arrested, hung upside down, and beaten until he confessed. On December 19, 1928, the 19-year-old was sentenced to 20 years.

Some version of Himes' criminal experiences appears in every discussion of his life and work. Situating the work inside the life is the biographer's job, but the breadth of context that Jackson brings to Himes is what makes the biography so necessary. Today, Himes' crime novels cast a long shadow, influencing generations of urban noir fiction, films, and television shows. He was the novelist who wrote unapologetically black characters involved in unapologetically black stories set in an unapologetically black Harlem of Himes' imagination. He told his own larger-than-life story in a pair of autobiographies, The Quality of Hurt (1972) and My Life of Absurdity (1976), candidly discussing his capacity for drink, barbed debate, white women, domestic abuse—and pointing out racism in the publishing industry, among light-skinned people of color, in the bourgeois left, America in general, and anybody else who might be keeping him from earning what he was due from his creative labor. When Himes passed away at 75 in 1984, he was better known in France than in his home country.

Jackson's meticulous research—in the three library archives that house Himes' papers, along with the papers and correspondences of people with whom he maintained at times fraught relationships, such as literary critic Sterling Brown, Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, publisher Alfred A. Knopf, photographer and patron Carl Van Vechten, Richard Wright—sketches the most detailed and nuanced charting of Himes' early years and life immediately after he got out of jail. This time period, the middle part of the 20th century, overlapped with Jackson's research interests, and he began to see in Himes a model for thinking about contemporary African-American masculinity.

"If you're looking at African-American men, Himes, to me, is the singular figure that helps us understand many of our pressing challenges," Jackson says. He lists a few topics off the top of his head. "Recidivism in the prison population, prisoners coming home to communities and moving back into the workforce, starting and raising families. People that are obviously talented but don't have credentials, and are perhaps barred from obtaining credentials. He helps us begin a discussion on some of these things."

Himes' life and work after prison, in fact, is what initially piqued Jackson's interest. In the 1940s, Himes authored politically and socially aware novels that put race front and center in understanding America at the time, which Himes wrote in his own arresting version of literary naturalism. His debut, If He Hollers Let Him Go (1945), is as admired today as it was in its time, but Jackson makes the compelling argument that its follow-up, Lonely Crusade (1947), is overlooked and underappreciated, and positions it as a key text in reckoning both Himes' subsequent career and later works.

"I eventually got around to the crime books," Jackson says, acknowledging how many readers and critics typically approach Himes. "But I came from the other direction."

Chances are, if you're familiar with Chester Himes, it's through one of the eight crime novels he wrote for the French Série Noire between 1957 and 1969, after he moved permanently to Europe in the early 1950s. Himes initially thought the books were simply a way to get paid. These novels made him famous in Europe, though not financially secure, but widespread American fans eluded Himes until the 1980s and 1990s, when publishing imprints such as Black Lizard and Vintage Crime began reissuing pulp writers. These were the Americans who had imbued cheap genre books with penetrating psychology, gripping prose, existential dread, double-crossing schemes, sex, violence, sex, knives, sex, guns, and, well, sex.

Image caption: Lawrence Jackson

Image credit: Will Kirk / Johns Hopkins University

Himes' hardboiled tales of Harlem police detectives Coffin Ed Johnson and Gravedigger Jones, black cops meting out justice that white society won't, established him as one of America's most gifted crime writers, and the defining black one. These are the books shouted out by the filmmaker and 12 Years a Slave screenwriter John Ridley, author/filmmaker Nelson George, and basketball legend and author Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. These are the books that get discussed by characters in the Netflix comic-book series Luke Cage, which follows an ex-con turned indestructible black superhero who fights criminal and political corruption in Harlem.

"Sometimes that work has been dismissed," Jackson says of the crime fiction, a genre often looked down upon by Himes' peers. With those novels, however, "what I started to realize was that [Himes] was having another range of experimentation and developing interesting characters that he regarded so highly that by the end of his career, he's saying the detective fiction is the best work he's ever done. What the detective fiction allowed him to do was to really be able to thumb his nose at middle-class standards of decorum. Some of that striving was personified by people like Ellison and Wright, who, for different reasons, would say to him that they thought he should do better or do different kinds of work."

Himes' iconoclastic, mercurial thoughts on race and class politics pepper any description of his work. Jackson's biography details how Himes was born into his class and color consciousness, as such tensions played out in his own family. Though both his parents were educated, his light-skinned mother, Estelle Bomar—proud, cultured, with little interest in seeking white society's approval but who could also scoff at lower-class/less-educated blacks—didn't always see eye to eye with his short, dark-skinned father, Joseph Himes, a blacksmith who taught metalsmithing at black colleges in the South until industrialization made such traditional labor obsolete. Chester, born in Missouri, grew up bouncing around the South until high school, when the family went to Cleveland to live with his father's sister. Neither of his parents was pleased with the move, and their marriage wouldn't last through Chester's graduation.

This detailed knowledge of Himes' early years allows Jackson to make some wonderfully human observations about Himes' writing. "I think that with the two detectives, Coffin Ed and Gravedigger, Himes was able to recover some of the traits of his father," Jackson says. "In the detective fiction, Himes gets to recover a love of soul food, and it's sort of like, 'Where's this coming from?'—especially from a writer living overseas. His father loved soul food, and his mother would always give him hell about it. You have it come out in these wonderful gastronomic moments in more than half of the detective fictions."

Jackson's research road to Himes began when he met Michel Fabre at dinner in the early 1990s at Ohio State, where Jackson earned his master's degree. The French scholar and his wife, Geneviève, co-founded the Center for Afro-American Studies at the University of Paris and came to know a number of expatriate black American and Caribbean authors, including Gwendolyn Brooks, Himes, Hughes, and Wright. Fabre was Wright's foremost biographer, and he had co-authored a compact Himes biography in 1997. In the early 2000s, Fabre was looking for an appropriate repository for his own papers, correspondence, and research materials. Emory University acquired Fabre's archives in 2002, the same year Jackson joined the faculty of Emory's departments of English and African-American Studies. Before he died in 2003, Fabre passed Jackson a box containing copies of his Himes research.

Image caption: Himes' life experience gave him a different view of what protest meant, what needed to be protested, and what racism looked and felt like in America.

At the time, Jackson had recently finished his first book, Ralph Ellison: Emergence of Genius, a superb biography of a towering black author who, surprisingly, hadn't been the subject of a biography before. Researching the Ellison book gave Jackson a practical education in piecing together a writer's life from a wide range of sources, and not only what's contained in the Ellison archive that the Library of Congress began acquiring in 1995.

Jackson's second book, The Indignant Generation: A Narrative History of African American Writers and Critics, 1934–1960 (2010), looks at the political, cultural, and economic milieu of black authors between those two signposts of 20th-century African-American literature—the Harlem Renaissance and the civil rights and Black Arts movements. This period overlaps with World War II, Jim Crow laws, a large chunk of the Great Migration, urban redlining, and the beginnings of suburbanization—the social conditions in which authors such as James Baldwin, Brooks, Ellison, Lorraine Hansberry, Himes, and Wright were creating their strongest works. This midcentury period produced a number of naturalistic black "protest" novels that offered more richly drawn and human characters than the racist stereotypes found in American fiction up to that time, Margaret Mitchell's best-selling Gone With the Wind being a case in point. These novels—such as Willard Motley's Knock on Any Door (1947), Ann Petry's The Street (1946), William Gardner Smith's South Street (1954), Frank Yerby's The Foxes of Harrow (1946)—all came in the wake of Wright's best-selling Native Son in 1940. Its story of Bigger Thomas, a working-class young black man responding to American racism, was a novel with which all black writers had to wrestle.

Himes' life experience, however, gave him a different view of what protest meant, what needed to be protested, and what racism looked and felt like in America. If Bigger Thomas suggested there was such a thing as black anger in America, Himes was going to show how complicated and vulnerable living while black in America really was in his second novel. "Lonely Crusade is a major work," Jackson says. "If the book were published today with some very, very minor changes, it would be absolutely contemporary—which is the hallmark of an enduring, significant work of art. And I wanted to figure out the person that created this in the mid-'40s, right after the Second World War."

Just as Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck's documentary I Am Not Your Negro, shaped by James Baldwin's unfinished memoir Remember This House, rekindled an awareness that Baldwin's thinking and writing remain pertinent and vital to understanding America right now. Jackson's Chester B. Himes has the potential to do the same for Lonely Crusade. This 1947 novel follows the college-educated Lee Morgan, who becomes the first black union organizer at a Los Angeles aircraft factory during World War II.

Lee has a loveless, abusive relationship with his wife, Ruth, whom he resents for having to support them when he was too prideful to accept the service jobs he was offered after college. Once hired by the union to recruit black workers, Lee finds himself being pulled in many different directions—dealing with the racism of the Southern workers who toil alongside black workers, dealing with Communist Party members who want Lee to choose class over race, dealing with anti-Semitism and class antagonism among blacks, dealing with the corporate owners and law enforcement officials who want to quash unionization efforts, and dealing with the white woman with whom he begins a racially charged affair. Himes' characters have lengthy, idea-filled discussions about class, politics, and race. Through Lee's experiences, Himes exposes American racism that exists within ostensibly liberal enclaves. As Jackson points out in his biography, at a time when Amos 'n' Andy was a popular radio entertainment, Himes was writing about a black man having sex with white women and talking about how defeating Nazis or Communists abroad isn't going to do much for black people in America.

Image caption: Through Lee's experiences, Himes exposes American racism that exists within ostensibly liberal enclaves.

Lonely Crusade isn't merely a novel of ideas, though, as Himes portrays Lee as a vulnerable, conflicted man who has to prepare himself to deal with a variety of potentially tense, if not outright violent, situations any time he leaves the house. Lee calls this feeling fear, but Ishmael Reed, a friend of Himes', better identified it in the Los Angeles Times as the constant state of anxiety and depression that black men experience in Himes' fictional universe. The novel is a startlingly intimate portrait of a man's intellectual and emotional evolution, somebody who at the novel's beginning acknowledges that letting "people go to hell in their own particular way was one thing that America taught him," can look at a picket line toward the novel's end and think: "Now Lee saw a group of Negro workers standing in sullen silence behind the white. He was struck by the similarity of these workers of two races. Now that both faced a common enemy with equal reluctance, there seemed to be no difference but color. And why should there be? Lee Gordon thought. All had been born on the same baked share-croppers farms, steeped in the same Southern traditions, the objects of the same tyranny that, together, they had not only permitted but upheld. They were bound together by their own oppression rendered by the same oppressors—their fears and their superstitions and their ignorance indivisible. Only their hatred of each other separated them, like idiots hating their own images."

With Lonely Crusade, Himes artfully crafted a more moving portrait of a political awakening than those plays, films, and novels typically touted for their progressive ideals: Marc Blitzstein's The Cradle Will Rock, Elia Kazan's On the Waterfront, Ken Kesey's Sometimes a Great Notion, John Sayles' Matewan, and John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath–none of which, it needs mentioning, put race in America at the forefront of their stories. And though Himes' novel was well- received by a few critics, the book was a commercial flop.

It fared no better in the press. The novel was politely dismissed by The Chicago Defender, The Baltimore Afro-American, and The New York Times, while Milton Klonsky, reviewing the novel for the fiercely leftist literary magazine Commentary, was downright racist and sexist: "Which leads us to an overwhelming question—what real difference is there between the style of this book written by a Negro and the style of the very American mob culture which humiliates and degrades his people? Lonely Crusade breathes the same suffocating air as the ads, the radio, the movies, the pulps. Although the author is himself a Negro, his book is so deracinated, without any of the lively qualities of the imagination peculiar to his people, that it might easily have been composed by any clever college girl."

"My favorite thing about Himes is he believed in intellectual combat," Jackson says, talking about how Himes pushed back against some of those reviews that seemed to completely misread his novel. "He believed in responding to his critics. He was an activist in that way, and it was completely unique because he didn't do it, again, to his cohort. He would do it in the pages of liberal journals. He knew that the conservatives were against the work, and he knew that the rabid racists were against the work, but the liberals were spending a lot of time patting themselves on the back. He absolutely disallowed that comfort, that complacency. He paid a heavy price for it, but nonetheless, he was deeply committed to that."

Himes left for Europe in the early 1950s and, aside from the occasional visit, never returned. Needing to make ends meet, he started writing the crime novels a few years after relocating. He never explicitly returned to the style and themes that he explored in Lonely Crusade, though the ambition that went into it is pretty easy to discern 70 years on. He wrote a novel that treated an American outsider in every sense of the word as something radical: a human being. In early 1946, while he would have been working on Lonely Crusade, Himes wrote a letter to The Chicago Defender columnist and NAACP executive secretary Walter White, in which he shared his thoughts about black heroes in books: "But there are many things against writing about Negro heroes. It requires a consummate skill, first of all. You have to write like God to sell a Negro hero to an American white public. In most instances it is a thankless task. White people of America can stand to hear the bitter cries of a suppressed people; in an odd sort of way it purges the slovenness from their ambitions and impels them to drive on to great white supremacy; it is a sort of bitter-sweet inspiration which we, Negroes, derive from the blues. ...But there are very few white people, including most white liberals, who sincerely want to hear of Negro heroes.

"However, if you give us a chance, we'll get some Negro heroes in—I, personally, will make you that promise."

In Lonely Crusade, he delivered on that promise. And, as he predicted, America didn't want to hear it. "With Chester Himes you have a writer who, maybe more than his contemporaries, was willing to admit masculine vulnerability," Jackson says. "Again, in part because he doesn't have college credentials, in part because he has a prison record that doesn't get pardoned until the end of the '30s, I think that emphasized moments of emotional crisis for him. It's one thing to live in a society where you have what some people politely call second-class status. It's another thing when even in the segregated world, you're relegated to the bottom of existence. This is what comes out in the novel Lonely Crusade."

Posted in Arts+Culture, Voices+Opinion

Tagged literature, race, lawrence jackson