In September 2008, Ivelisse Page, a 37-year-old mother of four, was diagnosed with colon cancer. Several weeks later, she had 15 inches of her colon and 28 lymph nodes removed. But in December of that same year, Page's doctor, Luis Diaz, an associate professor of oncology in the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, had to deliver the devastating news that the cancer had spread to her liver. He told her that she had just an 8 percent chance of surviving for more than two years.

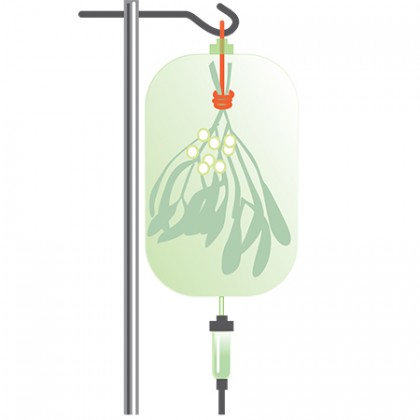

Page had more surgery to remove 20 percent of her liver, but instead of undergoing conventional chemotherapy, she pondered the suggestion of another of her doctors, Peter Hinderberger of Baltimore's Ruscombe Mansion Community Health Center. A specialist in using complementary therapies, Hinderberger had seen positive effects from injections of mistletoe extract. The liquid, derived from the poisonous, semiparasitic mistletoe plant, has been a popular natural remedy in treating cancer in Europe for years, but Hinderberger is one of the few physicians nationwide who regularly use the therapy.

Page and Diaz had never heard of the treatment. Diaz, who is also the director of translational medicine at the Ludwig Center for Cancer Genetics and Therapeutics at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center, reviewed several European studies on the extract and somewhat reluctantly gave Page the green light. "I'm an oncologist who treats with chemotherapy— and I'm really good at it—and here's somebody who says not only do I not want chemotherapy, but I still want you to be my oncologist while I'm getting mistletoe," Diaz says. "I reviewed the literature on mistletoe in other parts of the world and there is some acceptance of it. I was willing to work with her."

The next time the doctor saw his patient, he was amazed. "The one thing I noticed was that as soon as she went on it, she started feeling better," he recalls. "That's a universal feature I've seen in all patients who get mistletoe. Their [color] improves; they have more energy."

Page has been cancer-free since the operation on her liver and attributes her turnaround to a combination of surgery, diet and exercise, and the mistletoe. Now she's made it her mission to bring the extract from its European manufacturers to the United States, where the Food and Drug Administration has yet to issue its stamp of approval. She knew Diaz could help establish the necessary clinical trials. "I told her that the trials would cost millions of dollars, which I thought would subdue her a bit, but it didn't," Diaz says. "Instead, she went into overdrive." Page and her husband, Jimmy, formed a nonprofit called Believe Big to connect cancer patients with doctors who use nonconventional therapies and also to raise funds for the three-stage clinical trials. Through benefit dinners, fundraising walks, and donations, Believe Big has raised most of the $300,000 required for stage 1 testing, which could begin this summer. While Diaz says it's not uncommon for a nonprofit to fund clinical work, it's highly unusual for an individual to be the driving force.

Researchers at Johns Hopkins have been increasingly looking at naturally derived medicines to fight disease, Diaz notes. "Being at Hopkins rather than a private practice physician, my mission is to make things better, to improve treatments. I know that what we do for patients now isn't what the finality will be once we get it figured out. And I know that there needs to be new ideas."

Channing Paller, an assistant professor of oncology at the School of Medicine and the principal investigator for the study, says her colleagues are surprised when she mentions the mistletoe trials, but they realize that patients are interested in these new therapies. "In the past, doctors may have wondered if they were giving their patients snake oil," says Paller, who has worked on other Hopkins studies involving treatment of prostate cancer with pomegranate and an extract of muscadine grape skins. "But I think people are becoming a little more open-minded. We don't treat these natural products any differently than any other immunotherapy trial that we do. Every new potential treatment, including natural products such as herbs, needs to be studied rigorously and go through all FDA-required testing before it can be given to a patient."

Diaz says that in Europe, clinical trials for mistletoe have produced "confusing and mixed" results. Some studies have demonstrated improvements in patients suffering from certain types of cancers, such as breast, colon, pancreatic, or melanoma, but other studies have shown the treatment to be ineffective in reducing tumor size or preventing the spread of the disease. Paller says mistletoe's primary benefit could lie in its ability to boost the immune system, as studies have revealed that it can help patients better withstand the side effects of chemotherapy. Mistletoe extract's efficacy, safety, and dosage recommendations will all be thoroughly tested during the course of Hopkins' multiyear study.