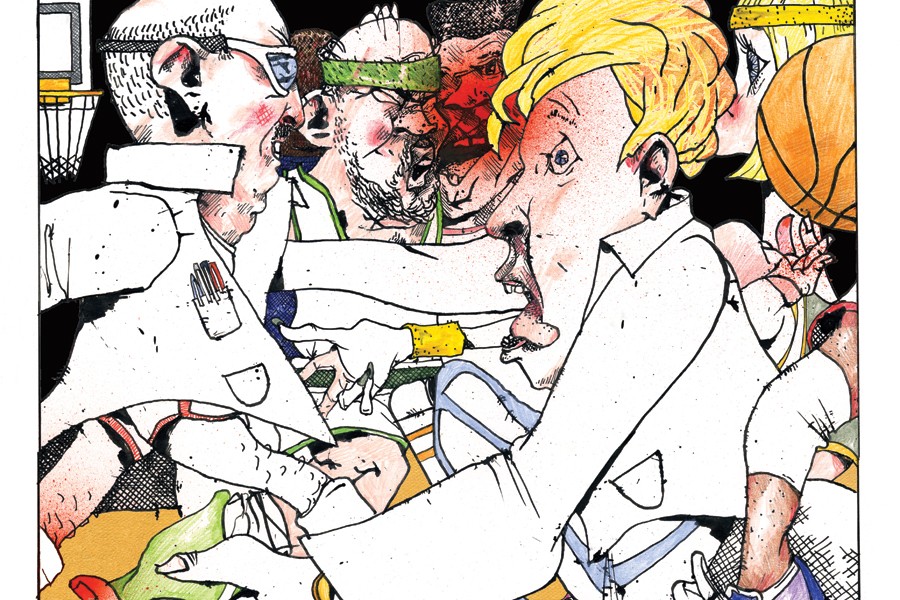

Game one started out fairly crisp, then deteriorated to a brick fest. The two teams—a collection of men who could be your older brother, uncle, or grandfather—traded a salvo of ugly shots and turnovers.

Layups were missed, rebounds bungled. The cluttered floor spacing would make a coach weep. Somewhere, the ghost of James Naismith likely shook his head and wished he'd never seen a peach basket.

But then came a moment of pure hardwood magic. Chuck, a six-foot-five-ish man in his late 40s and the husband of a Johns Hopkins staff member, threw a gem of a half-court outlet pass to Bill, a 67-year-old history professor and modern China expert, who shoveled a toss to Ralph, a white-haired, goggled astronomer, for an uncontested game-winning layup. That's victory, one university–style.

Now who's got next? Because here, there's always another game.

Each Wednesday and Friday at lunchtime, the clamor of screeching high-tops fills Homewood's O'Connor Recreation Center gym. Men—and the occasional woman—of various ages, heights, waistlines, and JHU connections coalesce for a little friendly and spirited pickup basketball. It's a tradition now in its fourth decade.

While there's some debate on exactly when the weekday-afternoon games started, the general consensus dates them to somewhere around the early 1980s, when a small group of faculty and various academic department staff met for hoops at the White Athletic Center's Goldfarb Gymnasium. But others soon wanted in. The originals were joined by grad students, alumni, athletic center staff, folks from maintenance and food services, employees from the nearby Space Telescope Science Institute, and anyone else who wanted court time.

Bill Rowe, the John and Diane Cooke Professor of Chinese History in the Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, considers himself the longest-tenured regular. Rowe joined Johns Hopkins in 1982 and not long thereafter sniffed out the campus basketball courts. "I grew up in Brooklyn, and I've been playing basketball since I was 8 at various blacktop courts and the local YMCA," Rowe says. "I'm not an athlete, and I've never been particularly good at basketball, but the sport is in my blood. I used to be able to mix it up more; now, if I can break a sweat, that's pretty good."

As Rowe tells it, not much has changed in the basic format in the past 30-plus years, other than location. (The games moved from the White Center to the O'Connor Center after the facility opened in spring 2002.) Those interested in playing gather at 11:30 a.m. As soon as a quorum of 10 is reached, two of the group's regulars choose "even" sides. "We start off by trying to separate the two tallest guys," Rowe says. "We understand the abilities of everyone out there, more or less, although sometimes it gets screwed up when somebody new comes into the game."

They play to 12, one point per basket. Winning team stays on the court. They usually have time for at least three games, four if bodies allow. It's full court. No clock. No scoreboard. No refs. They police their own fouls, but anything from the hardest hack to a travel results in the same, a reset of possession.

Offensive fouls, like the stray elbow or charge, go largely ignored. Arguments erupt on occasion, but according to most regulars, not as frequently as they used to. Age, apparently, mellows everyone.

Undergraduates, while not technically excluded, don't typically figure in the mix. "Plus, we're a little skeptical of undergraduates—they don't have a sense of mortality yet," says Rowe, who lists broken fingers, ribs, and a wisdom tooth among his on-court injuries. "We know that someday there'll come an injury we can't overcome. We've lost a few over the years to bad knees and back injuries."

The current group of regulars totals about 30, most on the other side of age 35. Anywhere from 10 to 20 show up on any given day.

The game's list of alumni includes the noted colonial America historian Jack P. Greene, literary scholar Stanley Fish, mathematician William Minicozzi, Baltimore Sun sportswriter Kevin Cowherd, and several WBAL-TV personalities, including Tony Pann and Lisa Salters, now with ESPN.

Salters, who played guard for the Lady Lions during her time at Penn State, tagged along with fellow WBAL employees who, like her, wanted to satisfy a basketball craving. "It was a great competition, [and] when I worked the night shift back then, I could play for a couple of hours, shower, change, and get ready for work," says Salters, who was a regular from 1988 to 1995 before moving to Los Angeles for ABC News.

One of the few women to play, Salters doesn't recall getting deferential treatment. "They just knew I had some game," she says. "I never knew what the others did [for a living]. They were just guys in gym shorts. I mean, you know who can shoot, who sucks. Sure, you learn a little about people, but mostly it's just about the basketball."

The play itself can best be described as uneven.

There are sporadic periods of brilliance when you'll see a stylish full-court pass to start a break, and a textbook jump shot ending in a silky swish. More often, the ball clanks off the rim—or misses it entirely.

Lester Spence, an associate professor of political science and Africana studies, started playing in the Homewood pickup games in 2005, just after he joined JHU from Washington University in St. Louis. He first shot hoops with students and asked one: "Where and when do the old guys play?"

Spence characterizes pickup basketball as a "higher form of communication," self-organized, and able to survive decades with minimal effort. "Nobody's in charge here. There's just an understanding everyone will be back," Spence says. "It's a community away from the community. We have arguments, sure, but they never get out of hand. Intellectually, you just figure s--- out on the court. And it's all first names. We load so much onto people because of status, but here you create a setting where status doesn't matter, other than your status on the court."

Spence says basketball likely saved his career.

"I was on the tenure track when I first arrived here, and I brought my own level of stress to the court," says Spence, who acknowledged the Homewood pickup games in his book Stare in the Darkness: The Limits of Hip-hop and Black Politics. "At the moment in time, I didn't know if I was going to stick around here, but this group, in particular Bill Minicozzi, was there when I needed someone."

Talentwise, most consider themselves from "passable" to "hacks." Spence says he has a "stable" game and can pass. "I know what I can't do," he says. "I play to compete."

Spence, too, has had his share of court-related injuries, including a herniated disc, a neck injury, and "general wear and tear" on his knees. But he's not stopping. "Basketball is a beautiful game, and means a lot to me. It's like breathing," he says.

Ralph Bohlin, who joined around the same time as Rowe, is 71, and not letting age slow him down. Bohlin, an astronomer with the Space Telescope Science Institute who specializes in the calibration of standard stars, says he has a "year by year membership" in basketball. He says he's missed a few months here and there due to injuries but has otherwise been playing 30 years straight.

"I do it for exercise, but the competition is also fun," says Bohlin, who is featured in an STScI recruitment video playing pickup basketball at the O'Connor Center. "It keeps me young and breaks up the day. I can't run up and down the court, or jump, the way I used to. But I'm still really good at pushing and shoving."

And every once in a while, getting a game-winning basket.

Posted in Athletics, University News

Tagged fun stuff