So what do both a centuries-old letter about a pranky cow and a pair of pre-adolescent girls have to do with the latest changes coming to a campus landscape? They factor in the new Homewood Orchard, nine heirloom fruit trees to be planted in September, with a ceremonial groundbreaking by President Ron Daniels on Sept. 4. The grove of apples and pears is just south of the Alumni Memorial Residences, where all are invited to enjoy their shade and bounty once the young trees are tall and productive.

The story begins in the year 1800. That's when some 130 acres of land over which much of Johns Hopkins' Homewood campus now sprawls was rural farmland that Charles Carroll of Carrollton (a Declaration of Independence signee and one of the young nation's richest men) presented to his son Charles Jr. as a wedding gift. Included in his nuptial largesse were funds to erect a genteel summer home, which was completed by 1802. Today we know it as Homewood Museum, the handsome Federal-style house perched between The Beach and the Freshman Quad. Other remnants of the erstwhile Homewood farm include its former carriage house (now the Merrick Barn, home of the John Astin Theatre) and a recently restored brick privy.

Over the past two decades, the exterior and interior of Homewood Museum have been painstakingly restored to approximate their appearances in the early 19th century. Period furnishings and accoutrements have been acquired to help the house museum provide an informed glimpse into an earlier time. What couldn't be changed, of course, was the built-up view out the windows, where a city bloomed and minds, not crops, are now nurtured.

"Part of what we are trying to accomplish here is to establish as much original context for this house as possible," says Homewood Museum director and curator Catherine Rogers Arthur of an orchard project designed to return some agricultural activity to the former farm. "We've long wanted to do this, but finally the rest of the world has kind of come around because the orchard speaks to issues of sustainability, which is what a place like Homewood was always about."

In other words, the 19th-century Carrolls were locavores before that trendy term even existed. Planting a small orchard seemed the best way to re-establish a link to a more self-sufficient rural past while also providing a green and pleasant space for the greater Johns Hopkins community. But with historical accuracy and authenticity guiding every move the museum makes, how does one know that fruit trees were part of the old Homewood farm? Fortunately, there's a paper trail.

"We knew they had an orchard here based on family letters from the time period," Arthur says. "Even before the house was constructed, Charles Carroll Jr. was setting about improving the property."

Indeed, the pivotal piece of evidence is a letter from Charles Carroll Jr. dated March 11, 1801 (though scholars now think that he was making a common mistake many of us do when dating things in a new year and that it should read 1802). It was written to his wife, Harriet, who was away in Philadelphia tending to her sick mother. In flowing quill-pen cursive, Carroll describes life at Homewood, where the house was going up and the grounds were already planted.

"I'm sorry to tell you that my blundering gardener has suffered the cow to get into the orchard and nip off the tops of almost all the trees," Carroll writes to his new bride. "The cow, which is a little pranky at times, I mean to have butchered in the morning."

Bad news for the cow—but good news for the Homewood folks looking to re-create aspects of the area's earlier agriculture as they now know there was an orchard here even older than the house itself. Other family letters have also been "fruitful," including one dated 1821 wherein Charles Carroll Sr. praises his son's gardening prowess and "understanding of how fruit trees should be managed."

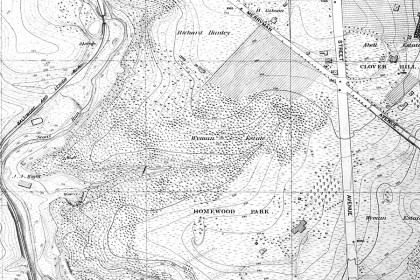

Another bit of orchard evidence comes some 100 years later on a ca. 1900 map of the current campus area, then called Homewood Park. This was just a few years before two prominent Baltimore families donated the land to the university so that it could relocate there from downtown. The map clearly indicates the house, some woods, and an area where trees are planted in rigid rows.

"The regular grid planting is indicative of an orchard," Arthur says. "The 1900 map indicates that it still existed, even at that point."

So now the issue shifts from whether there had been an orchard at Homewood to what fruits were grown in it. This question has proved a little more difficult. Since historical accuracy is the project's guiding principle, just heading down to the local home and garden superstore to buy the latest cutting-edge hybridized apple trees was out of the question.

"There is little record of exactly what they had here outside of a mention of Seckel pears in a letter," Arthur says.

Arthur began researching what fruit varieties early American orchards in the mid-Atlantic would have contained and came up with a list of heirlooms: Seckel pear and eight kinds of apple—Bevan's Favorite, Esopus Spitzenberg, Gravenstein, Lady, Roxbury Russet, Virginia Winesap, William's Favorite, and Yellow June. Although some of these antique varieties are slightly later than Homewood's end interpretive date of 1825 (the death of Charles Carroll Jr.), each relates in some way to an earlier cultivar. Peaches were considered, but eventually she went with an apple-heavy lineup. The trees were ordered and delivered to campus from a specialty nursery in the spring, but there wasn't time to arrange for their planting before summer. Besides, on arrival the trees were barely six feet tall.

"When the trees came in, they were incredibly young stock, so they were not ready to go into the ground yet," says Mark Selivan, the university's manager of grounds, resident arborist, and an adviser to the orchard project. "They needed to be husbanded a little bit longer to get up to size, and I kind of nominated myself to do it."

The trees spent the summer at Selivan's house, and here's where the young girls figure in. His daughters, Avery, 8, and Lily, 10, quickly adopted the spindly trees and fussed over them all summer.

"Both my girls helped me out with the trees," Selivan says. "They helped me wrap them up with cloth when it got cold, and they took them water every day, and we monitored for insects and disease. It was an opportunity for me to teach them, and a good family activity."

Selivan and his pro grounds crew will be in charge of the trees' maintenance and care once they are planted on campus. But he is not too worried. "I'm a licensed arborist in several states, including Maryland, and I grew up in an orchard, so I kind of know what to do," Selivan says. Besides, before coming to Johns Hopkins, he notes, he was "in charge of arboricultural and agronomical concerns" at the farm home of one Martha Stewart, the celebrated home and garden diva and media giant.

"I had a great time working for her," Selivan says. "She's a straightforward, successful businesswoman." And after managing the fruit trees and berry bushes for that celebrity taskmaster, looking after nine apple and pear trees beside freshman dorms, he says, "is going to be a cakewalk."

Posted in University News

Tagged homewood museum, university history