R. Champlin Sheridan Jr., who turned a $1,000 investment in a small magazine publisher called Everybody's Poultry into one of the nation's leading scientific, technical, and trade printing companies, died Aug. 7.

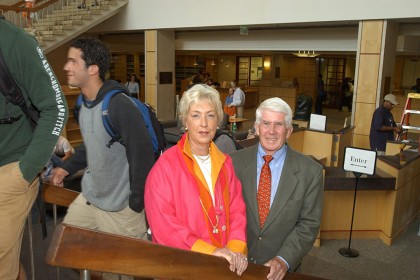

Image caption: Champ and Debbie Sheridan in Homewood’s Milton S. Eisenhower Library, one of Johns Hopkins’ Sheridan Libraries, in 2003.

Image credit: JAY VANRENSSELAER/HOMEWOOD PHOTOGRAPHY

Sheridan, whose retirement home was in Orchid, Fla., died at VNA Hospice House in Vero Beach of complications from emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and pulmonary hypertension. Sheridan, 83, a Baltimore-born printer and son of a printer, became a major philanthropic supporter of the Johns Hopkins University libraries in part because of what he called "sort of a natural affinity" for books and periodicals. He served as a trustee of both the university and Johns Hopkins Medicine and as a vice chair of the university's board. At his death, he was a Johns Hopkins trustee emeritus.

Known universally as Champ, Sheridan served in the Army in Korea during the Korean War, then returned to Baltimore to work for his father, the president and part owner of printer Schneidereith and Sons. In 1961, wanting to advance in his career but not compete directly with his father, Sheridan moved to Hanover, Pa., as production manager and later general manager of Everybody's Poultry Magazine Publishing Co., a small publisher and commercial printer. In 1967, he scraped together $1,000, "all the cash I had," he later said. He bought the business from his two retiring bosses and set about making it grow.

By 1987, he was ready for a new challenge and purchased a competitor, Braun-Brumfield of Ann Arbor, Mich. He combined it with what was, by then, the Sheridan Press to form the Sheridan Group. Today, that Hunt Valley, Md., company comprises five subsidiaries in Pennsylvania, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine, and Michigan. It specializes in scientific, technical, medical, and scholarly journals; scholarly books; trade and special interest magazines; commercial catalogs; publishing services; and printing technology.

Sheridan was the fourth recipient of the Lifetime Achievement Award of the National Association of Printers and Lithographers, awarded only occasionally to recognize graphic arts leaders for outstanding service to the association and the industry.

"Success really is a path; it's not a destination," Sheridan said in 1994. "It was not a case of dreaming where it would ultimately go. It's been my continual focus that if you got up each morning and put one foot in front of the other and make your best effort, you'll find at the end of the day that you've made a little progress. If you do that every day, you'll keep making progress," he said. "I really hadn't dreamed or sensed where we would be or what we would be able to do."

Sheridan, who graduated in 1948 from Friends School in Baltimore and in 1952 earned a bachelor's degree from Johns Hopkins, created a board of outside directors for the Sheridan Group not because it was required—the company was privately held—but because he thought it was important for the owner to be accountable to someone who could help him remain focused and directed.

He recruited to the board several trusted Johns Hopkins friends, including Ross Jones, a 1953 graduate now retired as vice president and secretary of the university; J.M. Dryden Hall, a 1954 graduate; and Donald Tate, a classmate of Sheridan's. Another close Baltimore friend on the board was Thomas O. Nuttle, a 1951 Cornell University graduate.

"Champ Sheridan was an unusual person," Jones says. "Unpretentious, modest, and hugely generous, he was the consummate entrepreneur who had a touch for growing his company by acquiring other companies in which he saw potential for increased revenues. And he seemed driven to give back the fruits of his success to support those organizations in which he and his wife, Debbie, had a special interest."

Sheridan later credited Jones with interesting him in supporting the university's libraries.

"Through Ross," Sheridan told the Johns Hopkins University Gazette in 2003, "I was given insight into what were the areas of the university that needed help. … We saw that the library is sort of an underdog that needs attention and often is taken for granted."

"I think that all of us … tend to live in a culture where you want to root for the underdog," he also said.

Champ and Debbie Sheridan gave $300,000 to kick-start a special library campaign, and in 1990 pledged $2.5 million, in part to endow the directorship of the Milton S. Eisenhower Library at the university's Homewood campus. In 1994, they made a $20 million commitment to nearly double the Eisenhower Library's endowment and to support renovations there.

William C. Richardson, then the president of the university, called the Sheridans "the library vision?aries of our generation" and said, "Johns Hopkins is fortunate beyond words to benefit from their devotion to the printed word and to the legacy of learning, and from their enthusiasm for innovation in scholarly communication."

In 1998, the university honored the Sheridans by collectively rechristening as "the Sheridan Libraries" both the Eisenhower and its satellite collections at the Albert D. Hutzler Reading Room, the John Work Garrett Library at Evergreen Museum & Library, and the George Peabody Library. The Brody Learning Commons, completed in 2012, is now also one of the Sheridan Libraries.

"Champ Sheridan was a remarkable man, and I am grateful to have been a part of his life," says Winston Tabb, Sheridan Dean of University Libraries and Museums. "His legacy of generosity and his genuine concern for the students of Johns Hopkins University will endure, through the libraries that bear his name and through the achievements of those whose work and research he helped fuel.

"Champ and Debbie truly transformed the libraries at Johns Hopkins through their immensely generous, multiple gifts," Tabb says. "Scholars for generations to come will benefit from their generosity. I will miss Champ's wit and candor, his advice, and his friendship; and I will always treasure the humble way in which he carried out what he characterized as his responsibility to repay, in his words, the 'kindness, love, and generosity' he had received as a student."

Sheridan, whose summer job after his freshman year at Johns Hopkins was hauling books for the library—"very physical labor"—said that a library "influences so much else at the university."

"It is," he said in 1994, "the cornerstone, the foundation of the university—the university as a forum for exchanging ideas and developing knowledge, not as a building or edifice." He said that he and his wife "felt we could have a more long-lasting and broader reach by focusing on the library rather than other portions of the university."

He did, however, also support the university's schools of Arts and Sciences, Medicine, Nursing, and Public Health; the Johns Hopkins Hospital; and the Johns Hopkins University Press.

"Champ's death is a terrific loss for the Johns Hopkins community, and our thoughts and prayers are with the Sheridan family," says Ronald J. Daniels, now president of the university. "Champ Sheridan's deep connection to Johns Hopkins over many decades was a vital part of who he was and helped to shape who we are today. His leadership and generosity across the university, in particular with the gift he and Debbie made to establish the Sheridan Libraries, truly embodied the ideals of Johns Hopkins University. Champ was someone who took his education and considerable talents and became quite successful. He was not interested in simply making his way in the world, however; Champ was interested in making the way a little easier and a little brighter for those who followed."

Sheridan retired in 1998, selling his business to BankBoston and moving back to Baltimore. After also purchasing a home in the Vero Beach area of Florida in 2002, the Sheridans became important benefactors of the Indian River Medical Center Foundation; in 2005, they were the first million-dollar donors to its $50 million campaign. A new surgical intensive care unit named in their honor opened at the hospital this year.

Champ and Beverly Ann "Debbie" Sheridan were married in 1980. His previous marriage, to Suzanne Stevens Sheridan, ended in divorce.

In addition to his wife, he is survived by his children: Sally Wright Sheridan, of Oklahoma City; Barrett Cathell Sheridan, of Mechanicsburg, Pa.; Richard C. Sheridan III, of Severna Park, Md.; Jon Strathmeyer, of York, Pa.; and Amy Beth Sheridan Fazackerley, of Alexandria, Va. The Sheridans have 10 grandchildren.

A memorial service was held in Vero Beach last month. Another will be held at 11 a.m. on Saturday, Sept. 7, in Baltimore, at Church of the Redeemer, 5603 N. Charles St., with a reception to follow at the Elkridge Club, 6100 N. Charles St.

In lieu of flowers, friends may consider gifts to the Sheridan Libraries of the Johns Hopkins University, at http://secure.jhu.edu/form/givenow; Indian River Medical Center Foundation, at http://irhf.org/index.cfm/fuseaction/giving.wog_makegift; or Visiting Nurse Association and Hospice Foundation at https://www.vnatc.com/home/pages/Donate.cfm.