New observations by the Messenger spacecraft provide compelling support for the long-held hypothesis that Mercury harbors abundant water ice and other frozen volatile materials in its permanently shadowed polar craters.

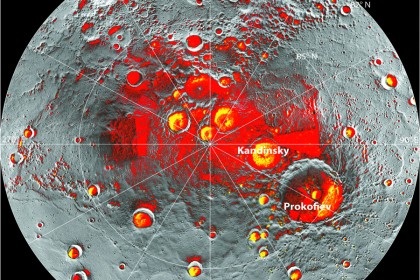

Image caption: Shown in red are areas of Mercury?s north polar region that are in shadow in all images acquired by Messenger to date. Image coverage, and mapping of shadows, is incomplete near the pole. The polar deposits imaged by Earth-based radar are in yellow, and the background image is a mosaic of Messenger images. This comparison indicates that all the polar deposits imaged by Earth-based radar are located in areas of persistent shadow as documented by Messenger images. Updated from N.L. Chabot et al., Journal of Geophysical Research 117, doi: 10.1029/2012JE004172 (2012).

Image credit: NASA/JHU Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington/National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center, Arecibo Observatory

This conclusion is supported by three independent lines of evidence: the first measurements of excess hydrogen at Mercury's north pole with Messenger's Neutron Spectrometer, the first measurements of the reflectance of Mercury's polar deposits at near-infrared wavelengths with the Mercury Laser Altimeter, or MLA, and the first detailed models of the surface and near-surface temperatures of Mercury's north polar regions that utilize the actual topography of Mercury's surface measured by the MLA. These findings are presented in three papers published online last month in Science Express.

Given its proximity to the sun, Mercury would seem to be an unlikely place to find ice. But the tilt of Mercury's rotational axis is almost zero—less than one degree—so there are pockets at the planet's poles that never see sunlight. Scientists suggested decades ago that there might be water ice and other frozen volatiles trapped at Mercury's poles.

The idea received a boost in 1991, when the Arecibo radio telescope in Puerto Rico detected unusually radar-bright patches at Mercury's poles, spots that reflected radio waves in the way one would expect if there was water ice. Many of these patches corresponded to the location of large impact craters mapped by the Mariner 10 spacecraft in the 1970s. But because Mariner saw less than 50 percent of the planet, planetary scientists lacked a complete diagram of the poles to compare with the images.

Messenger's arrival at Mercury last year changed that. Images from the spacecraft's Mercury Dual Imaging System taken in 2011 and earlier this year confirmed that radar-bright features at Mercury's north and south poles are within shadowed regions on Mercury's surface, findings that are consistent with the water ice hypothesis.

Now the newest data from Messenger strongly indicate that water ice is the major constituent of Mercury's north polar deposits and that ice is exposed at the surface in the coldest of those deposits but is buried beneath an unusually dark material across most of the deposits, where temperatures are a bit too warm for ice to be stable at the surface itself.

Messenger uses neutron spectroscopy to measure average hydrogen concentrations within Mercury's radar-bright regions. Water ice concentrations are derived from the hydrogen measurements. "The neutron data indicate that Mercury's radar-bright polar deposits contain, on average, a hydrogen-rich layer more than tens of centimeters thick beneath a surficial layer 10 to 20 centimeters thick that is less rich in hydrogen," writes David Lawrence, a Messenger participating scientist based at Johns Hopkins' Applied Physics Laboratory and the lead author of one of the papers. "The buried layer has a hydrogen content consistent with nearly pure water ice."

Data from the MLA—which has fired more than 10 million laser pulses at Mercury to make detailed maps of the planet's topography—corroborate the radar results and Neutron Spectrometer measurements of Mercury's polar region, writes Gregory Neumann of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. In a second paper, Neumann and his colleagues report that the first MLA measurements of the shadowed north polar regions reveal irregular dark and bright deposits at near-infrared wavelength near Mercury's north pole.

"These reflectance anomalies are concentrated on poleward-facing slopes and are spatially collocated with areas of high radar backscatter postulated to be the result of near-surface water ice," Neumann writes. "Correlation of observed reflectance with modeled temperatures indicates that the optically bright regions are consistent with surface water ice."

The MLA also recorded dark patches with diminished reflectance, consistent with the theory that the ice in those areas is covered by a thermally insulating layer. Neumann suggests that impacts of comets or volatile-rich asteroids could have provided both the dark and bright deposits, a finding corroborated in a third paper led by David Paige of the University of California, Los Angeles.

Paige and his colleagues provided the first detailed models of the surface and near-surface temperatures of Mercury's north polar regions that utilize the actual topography of Mercury's surface measured by the MLA. The measurements "show that the spatial distribution of regions of high radar backscatter is well matched by the predicted distribution of thermally stable water ice," he writes.

According to Paige, the dark material is likely a mix of complex organic compounds delivered to Mercury by the impacts of comets and volatile-rich asteroids, the same objects that likely delivered water to the innermost planet. The organic material may have been darkened further by exposure to the harsh radiation at Mercury's surface, even in permanently shadowed areas.

This dark insulating material is a new wrinkle to the story, says Sean Solomon of Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, principal investigator of the Messenger mission. "For more than 20 years the jury has been deliberating on whether the planet closest to the sun hosts abundant water ice in its permanently shadowed polar regions. Messenger has now supplied a unanimous affirmative verdict.

"But the new observations have also raised new questions," Solomon adds. "Do the dark materials in the polar deposits consist mostly of organic compounds? What kind of chemical reactions has that material experienced? Are there any regions on or within Mercury that might have both liquid water and organic compounds? Only with the continued exploration of Mercury can we hope to make progress on these new questions."