On a blustery late afternoon, Linda DeLibero, associate director of Johns Hopkins' Film and Media Studies Program, stands near the southwest corner of North Avenue and Charles Street, about a mile south of the university's Homewood campus. She examines a buff-brick and terra cotta building that has loomed here for nearly a century.

A padlocked and battered metal roll-down door marks the entrance. On the floor above, there's a small array of windows where numerous busted-out panes allow tentative peeks into the shadowy depths beyond. Higher still, near the cornice and catching the last light of the dying day, two words are engraved: Parkway Theatre.

This shuttered ghost—wedged between a boarded-up fried chicken carryout and a McDonald's drive-thru—doesn't offer much to look at, but, it turns out, there is a lot that can be envisioned. For this abandoned relic from the silent movie age is now poised to play a key role in the development and presentation of film in Baltimore in the 21st century.

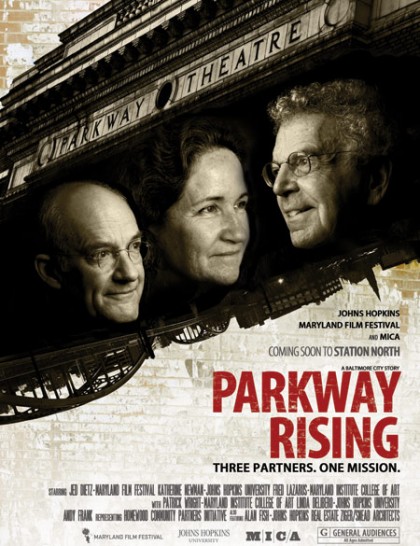

In December it was announced that Johns Hopkins and the Maryland Institute College of Art are partnering with the Maryland Film Festival, a Baltimore nonprofit that presents independent and historical films, in its nearly $17 million plans to bring back the Parkway as a three-screen, 600-seat film center and live performance complex. The redevelopment also will include facilities for use by the faculty and students of the two schools' film programs, which began holding joint classes last year, with the anticipation of further collaborations.

"It's all very exciting," says DeLibero, able to see beyond the graffiti-scrawled walls and broken glass of the present-day Parkway. "We'll have access to the theater space for our own programming and for MICA students and faculty. We are also looking to have spaces for classes and workshops and seminars with visiting artists. Taking on this big white elephant would really open up opportunities for all of us."

This city-owned "white elephant" hasn't been a working movie house since the 1970s and has been subject to numerous fruitless restoration schemes over the past decade. The Baltimore Development Corp., a nonprofit that provides economic development services to the city, spent much of last year evaluating the latest round of rehabilitation proposals for the theater and a pair of adjoining buildings before selecting the Maryland Film Festival plan. Depending on the success of design and fundraising efforts, hammers could start swinging here in 2014, with a reborn Parkway opening in September 2015 (almost exactly 100 years after the theater's grand opening, in October 1915).

The details of the proposed relationship among the three entities, along with the size of Johns Hopkins' financial commitment to the project, have yet to be ironed out, says Andrew Frank, special adviser to university President Ronald J. Daniels on economic development matters. However, he says, the university "jumped at the chance" to get involved as a means to further bolster the relationship with MICA's Video and Film Arts Department, which could lead to the formation of a graduate program in film. "We are committed to moving components of our collaborative film programs into the Parkway," he says.

But beyond the academic and artistic opportunities the Parkway project affords, its successful redevelopment falls perfectly in line with the goals of the Homewood Community Partnership Initiative, a collaborative effort that Johns Hopkins launched in 2011 with area civic and business leaders aiming to enhance conditions within 10 neighborhoods near Homewood, including Charles North, where the Parkway sits. Johns Hopkins has pledged to spend $10 million over five years on projects in line with the initiative's goals, with the hopes that this investment could serve as leverage to attract another $50 million in public and philanthropic support for neighborhood needs.

"One of the recommendations of the initiative is strengthening the corridor between Penn Station and Homewood by creating a safe, vibrant, and active Charles Street," Frank says. "This project obviously furthers that. It could also be a catalyst for other types of opportunities that may exist for Hopkins, MICA, and other institutions."

The initial architectural plans call for moving the theater's main entrance to Charles Street, into an adjacent commercial building (the former carryout), which, along with a row house to the rear of the Parkway, is part of the development parcel. The theater itself (known for the last 20 years of its life as the 5 West) dates to a glamorous age of moviegoing and was built with an ornate Louis XIV–inspired interior involving elaborate plasterwork and painting, though much of it has been damaged by the elements and vandals.

"We love the space, and we want to preserve and restore it," says Jed Dietz, director of the Maryland Film Festival. "The idea with the whole complex is to pair the faded historical beauty of the building with modern design." The main auditorium and its capacious balcony seating, he says, would be transformed into a 420-seat theater for film and music events. Two 90- to 100-seat theaters would be carved out of the pair of adjacent buildings, along with offices, academic spaces, and even a ground-floor restaurant. The architect for the project is the Baltimore firm Ziger/Snead, which is also presently involved with the conversion of a nearby former clothing factory into a nearly $18 million, transformational public middle and high school focused on teaching design, including architecture and fashion.

The Maryland Film Festival, formed in 1999, holds an annual four-day festival that draws thousands of attendees and scores of films and filmmakers from around the world. But the group also screens films, often in conjunction with talks and seminars, all year long—and all across town, including in Johns Hopkins' Shriver Hall and MICA's Brown Center. Dietz says that finding a permanent home for the organization and its screenings has long been a goal. His organization must raise the bulk of the multimillion-dollar Parkway price tag, though he hopes that state and federal historic preservation and neighborhood revitalization tax credits will be a part of the funding package. One thing is certain: His group of eager film buffs couldn't do it alone.

"While we have a lot of credibility with our programming, we are a small arts organization, and this is a big step," he says. "Partnering with Hopkins and MICA is hugely important for us, and their willingness to help is crucial."

MICA President Fred Lazarus says that he is "excited and optimistic" about the Parkway project, though, like Johns Hopkins, his school has yet to make a financial commitment to the initiative. "Clearly, it's the Film Festival's building, it's not our building, but we do see ourselves as partners and view its development as critical to Station North. They don't have near the development experience that either of our institutions has, so our staffs and boards are working closely with the festival on matters like fundraising and tax credits." Meanwhile, Patrick Wright, MICA's chair of Video and Film Arts, has been working with Johns Hopkins' DeLibero on exploring how the joint film programs might operate in the theater.

The Parkway resides within the Station North Arts and Entertainment District, a roughly 20-block area created in 2002 that benefits from city and state tax breaks and other incentives as a means to spur arts-related redevelopment. In 10 years' time, an area largely marked by disinvestment and grime has bloomed with a new creative vitality as galleries, studios, music venues, and storefront theatrical groups have sprouted within its boundaries, along with cafes, restaurants, and nightspots. Last fall, MICA unveiled its $18 million Graduate Studio Center at 131 W. North Ave., carved out of a former garment factory a block west of the Parkway. And the momentum continues, as a block east of the Parkway, a 60,000-square-foot North Avenue building erected in 1939 as a theater and radio studio is now slated to become a multipurpose arts space. All this artistic regeneration hasn't gone unnoticed by Johns Hopkins.

"It is very much in Hopkins' interest for the Station North Arts and Entertainment District to thrive because it is equidistant between Peabody and Homewood and provides amenities for our students, faculty, and visitors," Frank says.

Katherine Newman, dean of Johns Hopkins' Krieger School of Arts and Sciences, is positively bullish on the arts district and the potential for some of her school's programs to tap into the growing creative energy along North Avenue and beyond.

"The Krieger School is embarking on an expansion of its programs in the arts, and the Station North area will become the epicenter of this exciting development if everything breaks our way," she says. "Film is just one part of the equation. We are also searching for space to locate the Writing Seminars in a more expansive location in the same neighborhood, with opportunities for readings from poets and novelists, and to intersect both the film program, through screenwriting, and the drama program, through playwriting.

"This is an opportunity," she says, "to take Homewood out into the greater Baltimore community and expose our students to all of the excitement of the urban environment that surrounds us. It's a chance for us to help transform the Station North area into one of the most vibrant arts districts in the Northeast."

Posted in Arts+Culture, University News

Tagged katherine newman, film, andy frank, mica, homewood community partnership initiative